Chambering

By Victor Smith and Christopher Caile

|

If you are a karate student you probably chamber your non-striking

hand. But why do you do this, and what is the position of the chambered

hand? Also, why do different systems do things differently, and

why isn’t chambering explained by instructors?

There are many who disbelieve the worth of traditional technique,

including chambering. For in many fighting arts and styles the

non-striking hand is kept up to protect the head. Within their

narrow vision of combat, their interpretation is quite correct. |

|

|

|

In this historic photo Gichen

Funakoshi, considered by many to be the father of Japanese

karate, demonstrates how a chambering action by one arm pulls

the opponent into his punch.

|

So in explaining chambering it should be noted that there are vast differences

between fighting an opponent (practice fighting or in competition)

and the use of karate as self-defense against a random attack. Also,

there are vast differences between what is taught to beginners in terms

of technique and its use, and more advanced understanding of technique

and applications. Unfortunately the latter has been largely lost as

karate has expanded and evolved world-wide. The result is that entire

generations of students never learned, or looked to uncover, applications

of chambering.

Why do students just accept chambering? In my mind, if you as a student

do a technique and it isn’t effective, or the technique itself

can’t be used in the way it is practiced, you should view the

technique as wasted effort. My own assumption, however, is that there

is a value to everything within the ‘traditional’ karate

vocabulary, regardless of whether my instructor could or did tell,

show or teach me. So let’s amble through the layers of what I

see as the value or uses of chambering. But, first it should be noted

that pulling back one arm into chamber as done in practice as well

as kata only indicates the direction and method of an application.

When actually performed as part of a technique the chambering arm may

only pull back partially.

1. Against

a sudden grab from the rear. Every kata technique where you move forward

with one technique (including those where you move rearward)

and chamber one hand is building an automatic response against a grab

from the rear. The sharper you chamber, the sharper you strike back

(a rear elbow can be combined with a rear leg foot stop to the attacker’s

instep). Likewise double strikes become double rearward elbow strikes.

They don’t necessarily finish an attacker, but they have the

potential to create an opening for further response. The rear elbow

attack is often a staple of many jujutsu and self-defense systems against

a rear attack, or to create a momentary opening. Thus chambering should

be re-examined by karate-ka for similar potential applications. 1. Against

a sudden grab from the rear. Every kata technique where you move forward

with one technique (including those where you move rearward)

and chamber one hand is building an automatic response against a grab

from the rear. The sharper you chamber, the sharper you strike back

(a rear elbow can be combined with a rear leg foot stop to the attacker’s

instep). Likewise double strikes become double rearward elbow strikes.

They don’t necessarily finish an attacker, but they have the

potential to create an opening for further response. The rear elbow

attack is often a staple of many jujutsu and self-defense systems against

a rear attack, or to create a momentary opening. Thus chambering should

be re-examined by karate-ka for similar potential applications.

|

|

2. Against a sudden wrist grab from the front or the side. Traditionally

the first self-defense technique taught by Isshinryu karate’s

founder was to counter a wrist grab by sharply turning the arm over

(against the thumb which is relatively weak) to release the attacker’s

grip and then pulling the arm back into a chamber position. Here the

defender add a powerful knife-hand strike to a pressure point on the

attackers inner arm (very painful and can numb the arm) to assist in

the release.

3. Destroying an attacker with one technique. Here, chambering often

implies a technique using the retreating hand. This is a concept many

have a real problem with today. It’s often corrupted to “one

punch won’t stop a real attacker.” Of course they ignore

the reality in boxing, where, on occasion, a fight is finished with

just one punch to the jaw. So, one technique can stop a fight in the

right circumstances.

Of course there is the issue of what is “one technique.” A

piece of a movement, one movement or one series of movements all can

fit that quantification. One’s intent should be to: (1) try and

do it with one technique, yet (2) be instantly ready to go the distance

if you’re less than perfect.

Here it should be noted that chambering is more than just retracting

the hand. It’s retracting the hand while using correct body mechanics

and then looking at the rest of the body’s technique. Thus, if

you chamber one hand while punching with the other, chambering (pull

back of one hand and shoulder) can add power into the punch. But the

chambering movement also promises much more.

Hence if you grab somebody’s jacket collar, or wrist (of an opponent

who has his arms raised in a fighting position, as shown in this illustration)

and then sharply chamber that hand (pulling back) as you strike them

with a reverse punch or backhand into the jaw/neck/side of the head,

you first pull the person off balance, into your zone of attack, and

use the grab as a force multiplier to the strike. Your opponent’s

body isn’t free and can’t move away from the force of the

punch, so more of the impact is imparted into his body, creating more

shock. Hence if you grab somebody’s jacket collar, or wrist (of an opponent

who has his arms raised in a fighting position, as shown in this illustration)

and then sharply chamber that hand (pulling back) as you strike them

with a reverse punch or backhand into the jaw/neck/side of the head,

you first pull the person off balance, into your zone of attack, and

use the grab as a force multiplier to the strike. Your opponent’s

body isn’t free and can’t move away from the force of the

punch, so more of the impact is imparted into his body, creating more

shock.

This applied force multiplier has as much to do with chambering to create

stronger strikes, as the reciprocal nature of the chambering motion.

This force multiplier may not result in finishing an opponent with one

technique, but it certainly goes a long way towards that goal.

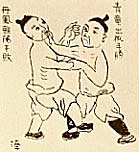

4. Another view of chambering is in conjunction with a block and punch, something

found in many Chinese arts as well as some older forms of Okinawan karate.

(1) For example, in Northern Mantis (Tai Tong Long), Northern Eagle Claw

(Faan Tzi Ying Jow Pai) and in the tuite (the art of grasping and grappling)

taught in Okinawa by Hohan Soken (2) and others, their methods include simultaneous

blocks, grabs and restraints. (3) For example, a block is often used to parry

and set up a grab (immobilization or pulling-in) before a strike. The hand

returning to chamber after a block simply slides down the arm to grab it

and yank backwards, or locks an arm in place as seen in this illustration

from the Bubishi. (4) 4. Another view of chambering is in conjunction with a block and punch, something

found in many Chinese arts as well as some older forms of Okinawan karate.

(1) For example, in Northern Mantis (Tai Tong Long), Northern Eagle Claw

(Faan Tzi Ying Jow Pai) and in the tuite (the art of grasping and grappling)

taught in Okinawa by Hohan Soken (2) and others, their methods include simultaneous

blocks, grabs and restraints. (3) For example, a block is often used to parry

and set up a grab (immobilization or pulling-in) before a strike. The hand

returning to chamber after a block simply slides down the arm to grab it

and yank backwards, or locks an arm in place as seen in this illustration

from the Bubishi. (4)

|

|

In another illustration the defender first traps the attacker’s

punching arm between his own (the forward arm moving inward and the rear

hand moving in and back toward a chamber position). This scissoring action

can break or injure the attacker’s elbow. The defender then opens

his forward hand to grip pressure points on the attacker’s bicep

(seen from the opposite side) while also pulling that arm backward (toward

chamber). The other hand attacks the aggressor’s eyes using a finger

technique.

The difference between those arts and modern karate is that the manner

in which they grab is more defined. Where in modern karate simply grabbing

and pulling is used, many Chinese arts and Okinawan Tuite practices use

more specific grabbing techniques (the fingers of the grabbing hand attacking

pressure points to create pain as well as to create a stronger grip)

to help maneuver or immobilize the opponent into a better lane or position

for striking.

5. Based on the above Chinese and/or Okinawan tuite model, I believe

that chambering in kata is used as a strength building tool. There are

several forms of strength being used. First, there is strength from using

the body in a more coordinated manner. A weight lifter needs correct

technique to lift heavy weights as well as body power. Likewise precise

kata practice enhances strength.

The

second more hidden strength building technique is actually the way

you tighten the hand as you chamber. This builds a stronger grip. This,

it should be noted, is not simply pulling your hand back. If you

ever

had the chance to train with somebody doing Eagle Claw for many years,

you discover the great hand strength they have in their locks (grips).

Here a double hand Eagle Claw grip is shown. One of the primary training

tools is actually the correct use of the hands in their complex forms.

Correct use of chambering can strengthen the grip. (5) The

second more hidden strength building technique is actually the way

you tighten the hand as you chamber. This builds a stronger grip. This,

it should be noted, is not simply pulling your hand back. If you

ever

had the chance to train with somebody doing Eagle Claw for many years,

you discover the great hand strength they have in their locks (grips).

Here a double hand Eagle Claw grip is shown. One of the primary training

tools is actually the correct use of the hands in their complex forms.

Correct use of chambering can strengthen the grip. (5)

In the same manner, those karate systems which include Kobodu (Okinawan

weapons such as the sai, tonfa, bo and jo) have actually followed the

Chinese model (likely unknowingly), as the practice of weapons actually

is also an incredible grip development tool.

Of course there are other ways to enhance kata practice. Drills with

partners, up to free sparring practices where grabbing and pulling while

striking are permitted, do so too. The study of karate isn’t as

simple as one tool; instead there’s an entire tool box involved.

|

This arm bar demonstrates how the rear

arm can be used in a semi-chambered position. |

|

|

In this historical

photo the famous karate pioneer Choki Motobu attacks

an opponent’s ribs with one arm while simultaneously

pulling back on the attacker’s other arm.

|

|

6. Likewise, a great range of karate’s potential block,

grab and chamber while striking moves don’t involve striking into

the body. Instead the strikes can be shearing planes of force across

the tricep’s

insertion to become variations of arm bars, attacks to the ribs, or as

shearing planes of force across the neck. Each of these examples strike

with the forearm sliding across the target instead of the punch into

the torso.

For example, the opponent might punch at you, and you as a defender

might respond with a technique that redirects that force in such a way

as to control the opponent and his attack. The result may be a projection

technique or one where you control the arm (as in the arm bar illustration

here) or head of the opponent.

This article represent only a small step into a very large body of

material.

Many don’t see these things, or won’t address these possibilities.

Perhaps, it’s simply that most students become comfortable in their

own practice or beliefs. This makes things easy. You aren’t challenged

and forced to stretch.

In my opinion, however, you can eventually see the Okinawn arts as a

vast grappling system of study (where chambering points the way) if you

choose to see what is actually there.

Footnotes

(1) Speaking of the Chinese systems,

Northern systems like Northern Shaolin (Sil Lum), Northern Mantis (Tai

Tong Long) and

Northern Eagle Claw (Faan

Tzi Ying Jow Pai), all chamber at the hip. But there are other systems

of Chinese combat which don’t use it, such as Yang Tai Chi Chaun

which has no chambering and uses a different paradigm for their combat

practices (review Dr. Yang Jwing Ming’s work on advanced Tai Chi

for ideas on how this is done). Likewise from what I’ve observed

Chinese wrestlers don’t chamber either. But the Chinese, with thousands

of systems, likely run the entire gamut of possibilities.

Some of the Northern System usage can be clearly seen

in Tuttle’s

publication this year of Shum Leung’s work on Eagle Claw.

(2) Hohan Soken, the great Okinawan karate pioneer

and kobudo expert (Okinawan weapons), was the sole student of Nabe

Matsumura

who in turn was the

inheritor of the Bushi Matsumura’s family system of Shorin-ryu

karate. His best known Okinawan students include Nihihara, Kise Fuse,

Kuda Yuichi and Nishihira Kosei. Many US students also trace their

training to Soken, including Roy Suenaka and others. The system is

unique for having a system within a system. In addition to Shorin-ryu

karate, Soken also taught senior students White Crane kata (Hakutsuru)

and techniques as well as tuite techniques inherited from the Matsumura

system.

(3) Tuite (sometimes spelled

Torite) was usually taught parallel to the practice of karate and to

more advanced

students. In

this capacity tuite

served as an adjunct art, something that could be applied in conjunction

with and added to standard karate skills to multiply the karate’s

effectiveness.

(4) For more info on this ancient text see the FightingArts.com

articles on this subject: “Enter

The Bubishi: Part 1- Introduction & Origins" and “Enter

The Bubishi: Part 2- The Text & Its Impact On Okinawa”

(5) For more information

Eagle Claw Kung Fu see these following FightingArts.com articles: “Inside

the Eagle's Claw” (http://fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=131)

and “Making The Eagle's Claw (http://fightingarts.com/reading/article.php?id=132).

About the Authors:

Victor Smith is a respected teacher of Isshinryu karate (8th degree black belt) and practionier of tai chi chuan with almost 40 years of training in Japanese, Korean and Chinese martial arts. His training also includes aikido, kobudo, tae kwon do, tang so do moo duk kwan, goju ryu, uechi ryu, sutrisno shotokan, tjimande, goshin jutsu, shorin ryu honda katsu, sil lum (northern Shaolin), tai tong long (northern mantis), pai lum (white dragon), and ying jow pai (eagle claw). Over the last few years he has begun documenting his studies for his students on his blog http://isshin-concentration.blogspot.com/ . He is an Associate Editor of FightingArts.com. Professionally he is a Senior Quality Assurance Technician, but also he enjoys writing fiction for the Destroyer Universe.

Christopher Caile is the founder and Editor of FightingArts.com

|