Martial Arts: Karate

Honoring Joe Lewis: His life & Lost Interview- Part 2

By Paul Maslak

|

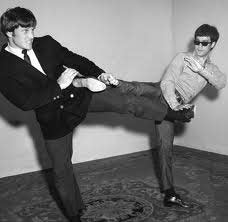

A youthful Joe Lewis clowning around with one of his acknowledged mentors, international action star Bruce Lee. |

Grand Master Joe Lewis - the legendary world heavyweight kickboxing and karate champion - passed away this past August (2012) from a malignant brain tumor. In tribute to his memory, FightingArts.com provides this two part article on Joe Lewis's life, including a lost interview from 1981 during which Master Lewis reflects on the origin of kickboxing, his personal mentor Bruce Lee and the first televised world championships that launched international full-contact competition. Part I was an introduction to Joe Lewis's life (up until mid 1975). Part 2 is the lost interview from 1981.

The Lost Interview

What follows is a previously unpublished interview with Joe Lewis that was conducted in late March 1981, and was reviewed for accuracy by both Lewis himself and reference author John Corcoran in July 2011. On the interview day thirty years ago, Lewis has retired from active competition and is awaiting the theatrical release of his second starring role in Force: Five. By then, a televised professional sport has separated itself from muaythai through its prohibition of striking-and-holding techniques, yet a contentious internal debate still rages over whether to include or exclude “leg kicks” and whether to call the new sport “full-contact karate” or by the simpler name that ultimately prevails: kickboxing.

With the momentous events behind this sport’s origin still fresh in mind, Lewis provides his behind-the- scenes impressions of the bygone “blood ‘n’ guts” light-contact karate mentality of the 1960s and early 1970s, when black belts believed they need train only for two-minute self-defense situations, when karate masters worried that boxing-gloved competition would destroy the empty hands effectiveness of their fighting techniques, and when Joe Lewis, almost alone, comprehended what would be demanded of his athletic colleagues to prepare for the martial arts as a professional contact sport.

Q: What attracted you to the martial arts?

LEWIS: When I was a child I had two idols. One was a guy named Dave Sime. At one time he was the fastest man in the world. I admired Dave Sime because he was also an intellectual, not just an athlete. He was studying at Duke University. He ran in the 1964 Olympics and this German (Armin Hary) beat him in the 100 meter dash (for the Gold Medal). But he only beat him by an arm’s length. So Dave looked at the film to find out how… This German was known to have an exceptional, very gifted ability to dive off the starting block very explosively. He would be two or three feet down the track almost before the other runners even heard the gun go off. They tested him and found that he was far, far above normal when it came to his ability to react to an external stimulus. So that became one of my goals: explosive speed.

My other idol was Paul Anderson (1956 Olympic Weightlifting Gold Medalist). He was once publicized as the strongest man in the world. They say that the Olympic champions in weightlifting are the world’s strongest, but people who know the game say the power lifters are the strongest. He was both weightlifter and power lifter.

What I wanted to do was put the two abilities together: Maximum explosive speed with the maximum amount of strength. Karate afforded me the opportunity to do that. I had no desire to be a competitive athlete. I just wanted to be an athlete.

Once I became a world champion, I started receiving recognition and visibility from all the networks. I got so caught up with it that I got off the track of what I really wanted out of life. I think it was fulfilling a number of needs that I had not fulfilled when I was a child. I wasn’t allowed to participate in school sports because I had obligations to work on the farm.

Q: Then how did you get started in karate?

LEWIS: Well, first, I joined the Marine Corps to cut the umbilical cord with my childhood. While I was in the Marines, I became involved in the martial arts. Physical efficacy was very important to me all of my life, so karate appealed to me very much. There was an aesthetic beauty in it that I liked.

I also liked wrestling, but I never saw a beauty in wrestling … though I still think wrestlers are the best conditioned athletes.

In the Marines, I chose to go to Okinawa to study karate. I heard that that was the place to learn. My first instructor was a tenth degree red belt, Eizo Shimabuku. The man who promoted me to black belt and who gave me my class, my integrity, my dignity and my character within the martial arts was Kinjo Kinsoku. Neither of them ever said anything about competition. It was my fellow Marines who were always talking about competing. The truth is, fighting in karate really came from the Americans.

Q: When you sparred in Okinawa, was it full-contact?

LEWIS: Yes, often it was full-contact. But it wasn’t like that everywhere. The Uechi-ryu and Goju-ryu schools were pretty big over there, and they did not fight full-contact. The schools I went to did both (full-contact and light-contact). But we always wore kendo gear when we fought. When I came back to the States, it was totally different: There was no full-contact, and that was really a letdown. It didn’t make sense to me.

My instructors always told me to stay out of competition, that it didn’t mean anything. But I competed anyway, feeling guilty for it, and I won the national championships. Six months later, I won the amateur world championships in Chicago. I was proud that I had won, but I was also very disappointed because, from my perspective, I had been cheated. I could not believe how out of shape and how lousy the black belts were in this country. I thought, geez, I’ve been in karate less than two years and if I’m the best in the country, what does that say about the standards of the athletes in this sport?

I won not only the fighting competition but I won the forms competition as well. I cleaned house. I went back to the military base and they were real proud of me ... wrote me up in the military paper ... and my hometown newspaper put me on the front page of the sports section. They made a big deal out of it.

After that, it was kind of downhill for me. I wasn’t out to beat anybody. I wasn’t trying to prove anything. It was just a mission. The real fun was in the gym, working with a sparring partner. That’s the real passion behind the sport of fighting. Competition to me was always nonsense.

When I got out of the service, I lost my sparring partners. I went around Los Angeles looking for good new sparring partners. I went to Mike Stone – he didn’t want to spar. Others turned me down. Chuck Norris was the only one who would spar with me. But he was so far away. Then the print media started pitting the two of us against each other. I didn’t feel comfortable going down there anymore.

Q: Were you still competing at this time?

LEWIS: Yes, but it still disappointed me that the sport wasn’t real. Going out there and just touching each other and having people say that you beat that other guy: To me, that was all nonsense. If you’re in a contact sport, the only way you can evaluate a punch or a kick’s effectiveness is to make an assessment on the results it produced. But if there’s no result, how do you judge? I just felt humiliated. I didn’t think it was fair, so I wanted to make the sport a reality. The national media weren’t dumb either. They weren’t going to have anything to do with the sport unless it was full-contact. So I decided in the latter part of 1969 that I wasn’t going to have anything more to do with karate unless it was for real.

The promoters were hot-to-trot because I was the big name then. So I told them, “I’m not going to fight anymore unless I can go full-contact.” So Lee Faulkner gave me my first full-contact match in 1970.

Q: Was that the first-ever kickboxing bout in America?

LEWIS: That’s right. But I had to find my own opponent. I went after those Shotokan guys first, the JKA (Japan Karate Association) boys in particular. Their arrogance was a little irresponsible: They resented it if you wanted to go over and fight in their closed tournaments, but they would consider it an insult if you invited them to come and fight in your open tournament. I thought they operated on that double standard long enough. I went to their best guys and said, “Hey, come out here and let’s fight in public, and let’s see what’s what.” But they told me they didn’t want to have anything to do with full-contact.

I wasn’t challenging them or anything like that, I just said, “Hey, you guys say that if it came down to the real thing you could beat me, so here’s your opportunity.” The top names in the country all passed until I came to this kid Greg Baines. He was biggest thing going then. He had beaten just about everybody. I thought he was about the best heavyweight in the US, if not in the whole world. And he was the only one who would fight me.

Bruce Lee was my instructor at that time. He worked with me for a couple years prior to the Greg Baines match. Bruce was a principle-centered trainer. In other words, he stressed techniques that adhered to certain guiding principles: good strong positioning, being able to bridge the gap fast, being explosive off the initial move, and mobility. Bruce Lee taught me how to put substance into my techniques.

Unfortunately, for several months before the match we could not work together. I had no trainer. I had no sparring partners. I came into the match basically all alone. I was working out at Chuck Norris’ karate school. I went down there every morning at 7 o’clock to work on the heavy bag, then I did a little roadwork in the afternoon.

I knocked out Greg Baines in the second round with a double right hook combination. The double right hook was one of the moves Bruce Lee showed me.

I got tired of full-contact right away because nobody in this country could fight. I felt kind of humiliated going out there and fighting guys who weren’t great athletes. They weren’t ready for me.

Q: Could you tell me a little about what Bruce Lee was like as a person?

LEWIS: Okay, well, I remember the thing I liked most about Bruce Lee was his boyish qualities. He was fun to be around. There was an energy that came from him. When you were in his presence, you felt ignited. You felt charged. I remember he used to like to draw. He was a very gifted and talented artist. And for some strange reason, people don’t know that about him … just as they don’t know that about me. It’s something that we had in common, that passion for the aesthetic, the beauty in the universe.

Bruce always played it down. Those were things he took for granted like I took the physical for granted. But his ego was all hooked up in the physical, trying to develop muscles like I had. He was always asking me questions like, “How do you develop this muscle? That muscle?” Muscular development was something that just came to me.

I remember one time, he and Lew Alcindor (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and I went downtown to Chinatown to eat. Bruce was always doing what I called “cutting the monkey”. That doesn’t mean misbehaving; it just means expressing yourself in a very free way. And he’d get very childlike. We came out of the restaurant and he was wearing a suit and a tie. He started jumping around in the parking lot, doing these Wing Chun forms. I would always ask him to do things. I would press his button. I knew he liked to show off. I’d say it in such as way that he’d be proud to perform. He loved to entertain people. So I’d say, “Okay, Bruce, let me see you do some of those flying kicks … some tornado kicks. I’ve never seen any of those in Chinese styles. Do Chinese styles really have any?”

Here we were wearing suits and ties and we’re coming out of a restaurant after eating and it’s night. That’s not the time to start jumping around.

Well, he’d say, “Are you kidding?” Then he starts flying through the air, doing these incredibly perfect broad angle 360 degree turns in mid-air, like a ballet dancer doing these kicks. It was almost like a kata; he had them all linked together.

In his mind, he could just choreograph four or five moves together instantly and make them work, and make them seem like a dance that he’d rehearsed many, many times before. He was that fluid and that free that he could just make moves interlock together. I loved to watch him jump around and have fun like that.

It’s interesting. People don’t know this about him: He was a real supersensitive guy. Sometimes people misinterpreted his sensitivity for insecurity. That was because they couldn’t believe that a person who was as sensitive as he was could be as powerful and as gifted as he was. They couldn’t deny his gifts, but they could deny his sensitivity. They would say, “Well, he’s not sensitive, he’s insecure. He’s on an ego trip.”

The top people in the film industry and the top people in the martial arts … they all treated him that way. But the Bruce that I knew had a couple goals that he wanted to fulfill. They didn’t make any sense to me, but they meant something to him: He wanted to be the first international oriental superstar and he wanted to be recognized by his peers as a master in the martial arts.

I didn’t see why either of those things was important. The thing I thought was important was the thing he never talked about: He wanted to do comedy. I think he would have been sensational at that because that was the part of him I liked the most. That was his real power. He really knew how to entertain people. He really knew how to make people feel good.

Q: I read in an old Martial Arts Illustrated magazine that Lee Faulkner’s US Kickboxing Association (USKA) was trying to set up a world title fight for you in 1971. Why did it wait until the first Professional Karate Association (PKA) world championships in 1974?

LEWIS: The president of sports at ABC-TV, John Martin, said he hadn’t put karate on the Wide World of Sports for years because they thought it was nonsense. But ABC said they had been following my career. They said, “Wherever you fight, Joe Lewis, if it’s full-contact, we’ll put it on the air.” So at that time, I was the only person in the country who could put karate on national TV. I asked the USKA promoters to get me a world title shot with the Asian champion. But there were no heavyweights in Asia. The heaviest guy weighed 162 pounds. Here I wanted to become a credible world champion and there was nobody to fight. I had all this power, but nowhere to use it.

Finally they set up a match. The promoters offered me a thousand dollars to fight this All-Asian champion. I said, “How much are you paying him?” They said, “$3,000.” I said, “Wait a minute. Sports Illustrated will do a write-up on this match, which is the biggest sports magazine in the world, and ABC Wide World of Sports will come in, put it on the air and they’ll give you $3,000 for the rights. Right off the bat I know I’m worth more than $3,000. How come you’re giving him $3,000 and you’re only giving me $1,000?”

They replied, “Well, he’s the champion. He’s known and you’re not.” I said, “Well, that’s an insult. I can’t even pronounce the guy’s name and I’m in the sport. I don’t know him. What makes you think he’s known over here?” But that was their attitude. So I said, “I want double what you’re giving him or I’m not going to fight.”

Now I wanted that title more than anything else in the world. I’d seen those Asian kick-boxers back then. They were good outside kickers but they couldn’t punch on the inside. They couldn’t take a punch either. I could drop a man with a six-inch punch with either hand. I knew all I had to do was get inside their legs, throw a left hook and the title would be mine. No guy who weighs 162 pounds is going to beat me. I don’t care how hard he can hit.

They asked me to lose ten pounds and they’d get this guy to gain ten pounds. I said, “Sure, I’ll do that.” But they wouldn’t pay me the money so, although it meant a lot to me, I turned it down. I stuck by my principles and I gave up something which would have meant more than anything I’d ever done in my life as far as sports go. It never came to be: The world heavyweight kick-boxing champion. It would have been a real credible title. Instead I said, “The hell with it,” and I retired.

Then I came out of retirement for the PKA championships in 1974 because I again had a chance to put the sport in the limelight and to get the credible recognition. We couldn’t get any Orientals to fight me, with no Japanese or Koreans in the heavyweight division. I fought this All-European champion (Franc Brodar). At the time Europe was really backwards in martial arts and the guy looked like a klutz. But it was a credible title and I won the world full-contact karate title. The PKA championships aired in about 40 countries around the world. From 1968 on, I was ready for a world title. I finally got recognized and that’s all I wanted.

Q: At the end of day, you became the country’s top tournament karate champion, you started the modern kickboxing movement, you brought full-contact competition to national television, and then you capped it all off by establishing the first heavyweight world crown. At that point, did you feel your sports career had hit its highpoint of success?

LEWIS: Oh, absolutely not... I remember an interview I saw once where gossip columnist Rona Barrett asked Willie Nelson a similar question. I was in awe of the answer Willie Nelson gave. I’m paraphrasing now, but Willie said, “Rona, my sister and I used to love to play the guitar and sit down together and just sing. We just loved and enjoyed the hell out of it. We used to do it all the time. One day, the high school asked us to play in the auditorium for the school.”

Nelson had never thought of playing for other people. It was just something he loved to do. He said he experienced himself playing for those people the first time he ever played for an audience. He realized right then what success was: “Rona,” he said, “I’ve always been a success because I’ve always done what I’ve always loved.”

That’s my definition, too. Doing what you really love doing for yourself. You’re not thinking about anybody else or anything else. You’re not making any evaluations about what you’re doing. You’re not thinking about achieving any goals, but you are enjoying sharing something with yourself. You have that innate feeling that it’s right, that it’s life-centered, and that it’s productive. The fact that someone else enjoys it, or wants to pay you for it, or wants to say that it’s the best in the world – that’s all extra. But that’s not success.

Success produces those things. It’s not the result of those things.

About The Author:

A past Inside Kung-Fu editor-in-chief and martial arts book author, Paul Maslak served as the first WKA and KICK ratings commissioner. Between 1980-89, he administered the independent STAR System World Kickboxing Ratings as syndicated in fifteen sports magazines across the globe. More recently, he produced over a dozen motion pictures for cable television. For further historic information, visit the STAR ratings archival website at StarSystemKickboxing.net. |