Martial Arts: Kata and Applications

Sanchin Kata Fundamentals

By Kris Wilder

The basic kata sanchin has existed a long time, and has developed into variations called saifa, seiyunchin, shisochin, sanseiryu, seipai, kururunfa, and suparunpen, which are still practiced. The Goju-Ryu karate formed by Chojun Miyagi created the tensho kata, which is an open-fisted kata, as opposed to the gekisai kata. Sanchin is the basic kata used to build karate strength (kanren kata), which is the foundation for all of these kata. The basic kata sanchin has existed a long time, and has developed into variations called saifa, seiyunchin, shisochin, sanseiryu, seipai, kururunfa, and suparunpen, which are still practiced. The Goju-Ryu karate formed by Chojun Miyagi created the tensho kata, which is an open-fisted kata, as opposed to the gekisai kata. Sanchin is the basic kata used to build karate strength (kanren kata), which is the foundation for all of these kata.

The very basic kata in Okinawa-style karate is sanchin, and it has been understood historically that you master karate only if you master this kata.There is also a saying that karate begins with sanchin and ends with sanchin, and karate fighters should practice sanchin every day, three times.

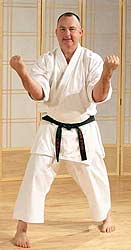

Karate posture is created by the sanchin kata. It is important to have a stable posture when fighting. A practitioner has to be able to stand firm when attacked, and be ready to attack back. The most important aspect in the sanchin posture is the power of Tanden, which is the central strength in a practitioner. A practitioner will lose to a bigger fighter if only muscle strength is used, and not the Tanden power.

Power is created in a combination of correct respiratory breathing and correct posture, which creates tension. It is therefore possible to continue fighting and practicing strong karate as you get older, when this kata is used. A physique strengthened from karate is not created only from muscle strength, but from a flexible muscle tone. It is not possible to perform strong karate without this characteristic. A body strengthened with bodybuilding will have an adverse effect. Bodies with hard, inflexible muscles will slow the karate movements of the body.

Important elements of martial arts (Budo) are the combination of mind, body, and spirit. The mind should be in a stable normal state, and actions should always be taken in a stable mental state. It is not possible for a peak performance if the mind is unstable when preparing for a fight. The respiratory technique of sanchin is how you learn to stay stable. The attempt to fight will be half hearted if the technical aspect of sanchin has not been mastered. The beginning of a correct technique is correct posture, which is to straighten the spine, pull in the chin, and tilt pelvis up. This posture will enable you to receive blows from any angle. In order to build a body for karate fighting, you do not only build muscle strength, but make use of the bone structure in order to use logical movements and flexibility from muscles. It is therefore vital to repeat training of sanchin in order to build a body for karate.

The richness of knowledge presented in the sanchin kata is a treasure that has been lost or limited to a very few for a long time. To discover this treasure, we must challenge ourselves to participate in the kata as it was originally intended. As we do so, we will certainly find that sanchin kata is a far cry from the modern form of karate as practiced by most today.

Three Battles - Mind, Body, Spirit

Each kata is examined from three perspectives —mind, body, and spirit. Using this method of examination with sanchin kata, let us first consider the mind. The very act of practicing sanchin kata changes the way the one looks at karate and fighting. Once the practitioner gains the realization of what fighting truly is—the power and damage that can occur—the mind of the practitioner changes. Now, let us consider the body, which experiences change as well. This physical aspect of sanchin kata is the most sought after aspect of training in this kata. Oddly, it is the easiest of the three to achieve. The sanchin kata posture is not like that of the typical Western body, with its broad shoulders and tightly strung muscles. It is, in fact, unattractive by Western standards—the crunched down and rolled shoulders of sanchin kata at first glance imply an aged or infirm body. However once the strength of sanchin kata is trained and understood, the body will choose this physical position over the classic Western position of shoulders held high, chest puffed out and leaning up on the balls of the feet. Finally, the spirit is changed when the mind comprehends what it is truly doing with respect to fighting, the body begins to adjust to its sanchin kata structure posture, and the resulting increased power and speed begin to show themselves. This change can best be described as the kind of spirit an adult would demonstrate to a child who was attempting to fight or cause injury to the adult. The adult understands the situation in a different way and as a result behaves differently—their intent, their spirit, is not the same as the child’s.

To the classic practitioner of sanchin kata, none of these perspectives—mind, body, or spirit—excludes the others. Some difficulty in understanding sanchin kata comes from the source of the kata. Although there is no one fountainhead, the language barrier is the largest of these founts of misunderstanding. Chinese, translated to hogen, to Japanese, then to English, with regional dialects at each juncture and translations of translations makes for a difficult transfer of accurate information and knowledge.

The importance of what appears to be the simplest of kata should not be overlooked because sanchin kata forms the hub from which all other kata radiate. It is not important as to whether a kata was created before or after sanchin because sanchin kata holds within in it certain undeniable truths.

Sanchin kata is given a place of honor and respect within the many karate systems that use it, yet it is often not explained, taught, or examined with the intensity and depth required to gain better understanding. For those who practice sanchin kata, the impact of the techniques inside this book will be immediate and positive. For those who do not practice sanchin kata, there is still much to be gained in understanding body mechanics and application of techniques found within this most universal and comprehensive form. The Way of Sanchin Kata illustrates long-overlooked techniques and principles that when applied will radiate throughout your karate, making it more powerful and effective than you will have thought possible.

Sanchin kata is not like other kata in that it stands alone, different and unique. It simply is not cut from the same cloth of other kata. In the past, karate masters learned sanchin kata and maybe one or two other forms. This way of instruction formed the core of the empty-hand martial arts from the Ryukyu archipelago. The reasoning was clear and uncomplicated: understand the context of empty-hand fighting through sanchin kata and learn the content of a fight with other forms.

Sanchin kata offers a compelling illustration of these Eastern precepts, aiding the practitioner in unifying the body, mind, and spirit, helping to connect with the earth and bring a balance to one’s existence. If we always wear shoes, and drive everywhere, the feet become weak and function merely as appendages rather than full participants in the locomotion of our bodies. While performing sanchin kata in bare feet, tendons and muscles are activated that are simply not exercised while wearing shoes. In addition, a connection to the earth is achieved, especially when done on the bare ground or a wooden floor. Movement, breath, and action are an important part of the very existence of a person. Sanchin kata incorporates movement, breath, and action, but does it in a way that focuses on self-defense as well.

Ancient Wisdom

The true history of sanchin kata is lost to time. Many will claim they know the true and correct history of sanchin kata, but factors such as where one chooses to begin and end can create one of many versions of the same history. The goal of this book is to achieve a better understanding of sanchin kata through the mechanics, history, and applications of the kata. It is only possible to touch upon a handful of points on the timeline with reasonable assurance when looking at the history of sanchin kata. According to the history of the Goju Ryu lineage, Kanryo Higashionna (1853-1915) brought sanchin kata back to Okinawa. That is not to say that sanchin kata had not been introduced to Okinawa before. It simply means the version that Higashionna brought back was taught by him to students who propagated the form by teaching it to others. Around 1918, Kanbun Uechi brought another version of sanchin kata to Okinawa and began teaching what would later be known as Uechi Ryu. As the reader can see, many paths for martial arts, as well as many paths for sanchin kata can be identified. Tracing that history involves a great deal of sifting through a rich mix of history, mythology, legend, and cultural prejudices often indistinguishable from one another. That is why nobody knows for sure about the origins of sanchin kata.

These many paths of course, are a result of change—both deliberate and accidental—to the practice of sanchin kata. Some might argue that in the case of martial arts and its forms, change is bad. On the contrary, the key to the concept of change is context. If change is a result of suiting the needs of the practitioner enacting the change, it may well be credible. However, change can result from mistranslation of a movement, or a misunderstanding of the intent behind a form or an element. While some changes are credible, e.g., are made consciously to suit one’s needs, others are accidental.

As changes, accidental or deliberate, take place, in some instances the forms become more simplified and in others more complicated. Soon many paths are created. Over the years, different versions of sanchin kata have arisen, many of which are in use today. Even within the same systems or styles, one will find differences. Some versions of the form include one-hundred-and-eighty-degree turns. For example, there are versions of sanchin kata that face in only one direction during the performance of the kata never turning. Some versions of sanchin kata turn. Some versions have opened hands and others have closed hands. Some submit that closing the fist closes off the Ki (or Qi) and others would say it makes the kata stronger turning the Ki back into the practitioner.

Tracing Back the Roots

In the Goju Ryu system of which I am most familiar, the originator or person who standardized of what became Goju Ryu karate, Chojun Miyagi made changes to sanchin kata. Miyagi took the open hands of the form and closed them to fists. Miyagi then took out the turns in the form his instructor Kanryo Higashionna taught to create another version of the kata. Miyagi also changed the breathing taught to him making it more direct and less circulatory in nature. Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo took the principles of the jiu-jitsu he had learned as a young man, removed the crippling techniques, created rules for competition, and emphasized throws. Gichin Funakoshi changed his native karate from an Okinawa tradition into a Japanese way to better suit the needs of the Japanese mainland culture. Morihei Ueshiba created aikido from his experience with jiu-jitsu after an epiphany. Today all of them are cited as masters without question. The list of people changing their art to suit their needs more closely and the needs of their students extends well beyond these examples given. The changes made by these three masters are profound. They were not made without going through a very clear process of gathering the data, analyzing the information, and then making the leap to wisdom.

The book, Five Ancestor Fist Kung-Fu, The Way of Ngo Cho Kun by Alexander L. Cho offers a straightforward path of sanchin kata through the kung fu system, “The kata taught by Miyagi are the sanchin kata and tensho. The sanchin kata of Goju Ryu is notably similar in principles and movements to the sam chien of Ngo Cho Kun. The movements and principles of the tensho kata are also strikingly similar to Ngo Cho Kun, and it seems the similarities are by no means coincidental. Uechi Ryu, another major Okinawan karate style, also bears striking resemblance to Ngo Cho Kun.”

Taijiquan (Tai Chi Chuan), The Grand Ultimate Fist, is often considered one of the three sisters of kung fu: Hsing-I, Baguazhang, and Tai Chi Chuan. Tai Chi is often taught in the western world as a form of health exercise but it is also a devastating martial art when employed in the hands of a knowledgeable practitioner. The very beginning of one Tai Chi segment, “Grasping the Sparrow’s Tail,” looks very similar to the opening of sanchin kata. Ngo Cho Kun, the Five Ancestor Fist Kung-Fu, uses a kata called sam chien, and the similarities between the Okinawan version of sanchin kata and the Chinese version of sam chien are not coincidental. The fact of the matter is that the Okinawan version of sanchin kata, no matter what the school or ryu, derives from forms originating from mainland China.

The work of uncovering, deciphering, and contextualizing historical information is a task that must involved educated speculation where contradictions, limited and unreliable source material and other hurdles exist. The goal is to present probable conclusions where possible, and to raise compelling questions where the truth has been lost to time.

Regardless of which system one chooses, what matters is that certain constants are necessary for success, ‘success’ being defined as:

-

Gripping the ground. This is interpreted as using the ground to generate power in holding one’s position or striking power.

-

Skeletal architecture. The alignment of the bones to provide static strength.

-

Muscular tone. Using conditioned muscles to move the body swiftly and in a way beneficial to the technique being done.

-

Moving the Ki or Qi (universal energy). Using intent and bioelectric energy to assist in movement.

Calming the mind to mushin, or “no mind.” Removing internal chatter to allow the mind to function more efficiently.

Regular practice of Sanchin Kata conditions the body, trains correct alignment, and teaches the essential body structure needed for generating power within all of your karate movements. Many karate practitioners believe that Sanchin Kata holds the key to mastering the traditional martial arts. Though it can be one of the simplest forms to learn, it is one of the most difficult to perfect. If the other kata are the trees, Sanchin is the rain that nourishes them all.

About The Author:

|

If you are interested in more information on Sanchin, Chris Wilder's book is available in FightingArts e-store. |

Kris Wilder began his martial arts training in 1976 in the art of Tae Kwon Do, he has earned black belt-level ranks in three arts: Tae Kwon Do (2nd Degree), Kodokan Judo (1st Degree) and Goju-Ryu Karate (5th Degree), which he teaches at the West Seattle Karate Academy. He is a regular columnist for Traditional Karate Magazine. Kris is the author of the DVD, "Sanchin Kata" and of "The Way of Sanchin Kata" and several other books. |