Training In America’s First Taekowndo School

By Herb Borkland

|

Herb Borkland in 1963 hosts his

Emmy-winning TV show, “Teens,” which publicized America’s

first taekwondo school. |

Bill "Superfoot" Wallace once called me a liar in public when

I mentioned I had been an original student, by Jhoon Rhee's personal invitation,

at the first taekwondo school in America.

This happened in the late Nineties. We were finishing up a restaurant

diner with the producer of a weekly national half-hour ESPN cable-TV show

I hosted called "Black Belts." Wallace had been a "special

guest" invited for one episode into the broadcast booth with me and

my color man, Master (now Grand Master) Dennis Brown.

I didn't know, back then, that, in his public appearances, the same crowds

who press in close to meet the full-contact legend are usually edging

away, with funny looks on their faces, after the first couple minutes

around Bill.

Ironically enough, it had been thirty-odd years earlier that my hosting

another TV show called "Teens" had made it possible for a Washington,

D.C.-born teenager to be one of the first people ever to conduct an on-air

interview with (now) Grand Master Rhee, the father of American TKD.

|

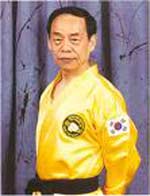

Jhoon Rhee. In 1962,

Master Jhoon Rhee, “Father of American Taekwondo”, opened

the USA’s first TKD dojang. Based out of Washington, D.C.,

he founded the international taekwondo organization which bears

his name and went on to pioneer foam-dip sparring gear, musical

forms, and teaching martial arts to children. He became internationally

famous as “Congress’s Karate Master” and over

the years instructed prominent Senators and House members. After

the fall of the old Soviet Union, Jhoon Rhee traveled to Russia

as a good-will ambassador and succeeded in having its national ban

on martial arts lifted. The subject of countless articles in martial

arts and mainstream global publications, today Grand Master Rhee

is widely recognized as one of the most influential American martial

artists of all time. |

This would be a slim claim to fame, except that meeting Jhoon Rhee changed

my life forever. I became – or realized that I had somehow always

been born to be – a lifelong, career martial artist.

I will never forget the impact in 1963 of seeing a few of Master Rhee's

brand-new students (including one woman! unheard of!) doing Korean kick-punch

drills under the black-and-white klieg lighting in the "A" studio

of CBS/channel 9's Broadcast House.

To a six-five, 17-year-old such as I was, young Master Rhee seemed, when

we first shook hands right before air time, like a short Asian army officer.

However, from the dark, military-cut hair down to his spit-polished black

ROC uniform dress shoes, the impression of engaging a larger man grew

on me during our live, on-air interview.

The Master moved and held himself as if compacted like a steel spring

under pressure, but without any visible tension, either. The feeling in

the air around him was charged by purpose. He had what ever since the

John F. Kennedy Presidential election we had learned to call "charisma,"

as if Rhee were a man who saw farther ahead and from a higher vantage

point than most people.

In good English, confidently and without haste, Rhee explained about

Korean "karate" during the "bizarre" exercises the

home viewers' were watching – line drills: kick-punch-kiyup, over

and over, up and down the studio floor.

I thought Rhee had an interesting face for TV, when I glanced at the

monitor screen set up off-camera. At a time when most Asians we saw were

silly comics, ingratiating restaurateurs or sniveling movie villains,

Rhee looked quietly and unapologetically powerful.

After the show, he invited me to come join his school. Maybe he saw the

gleam in my eye and recognized a born-hardwired martial artist back in

the days before anybody even knew there could be such a destiny for a

20th century American.

How to explain? In the playgrounds of the Korean War Era, educators took

it for granted that boys fought during recess. Since men controlled education,

they remembered from their own youth that this, far from being brutal,

un-PC "bullying," this was one of the normal, natural way boys

made friends. Our teachers didn't let it get out hand. Tears led to a

subtle sense of being looked down on by those men, most of whom had fought

in war. Boys were expected to "cowboy up." Their war would be

coming along soon.

Mas Oyama had taken a publicity tour in 1952 through the US, fighting

and (reportedly) beating all comers, boxers and wrestlers, and performing

astounding bare-handed rock breaking. I never personally saw the great

Japanese stylist, but I do recall being told by a kid, around the lockers

one afternoon, "karate is death in three blows."

Those words burned into my noggin. What power! I didn't want to kill

anybody, of course. Mostly, rolling around in the playground dust, we

wrestled – I knew about the mount position before I got out of fourth

grade – and some also used a little gentled-down combat jiu-jitsu

taught by fathers and uncles who'd learned it to fight hand-to-hand with

the Japanese during WW II.

So I'd heard of karate. Over the years, I had bribed kids to let me practice

judo throws on them, but seeing what Jhoon Rhee had brought to town, I

was ready to go learn. There had already been a few street fights, and

I knew first-hand how elbows can chip your teeth, but also how, after

you spit out the broken bit, you cool down fast to a focused fury, so

you won the fight.

But the switchblade knife was to our generation what the nine is to Hip

Hop. Kids began pulling knives on me, too; so I figured guns couldn't

be far behind, and I wanted to know what to do. I took Master Rhee up

on his offer.

The first TKD school (there had only been a few informal clubs before

now) was a second-story space up in an old urban building a few blocks

below Dupont Circle in North West Washington. Our dojang had that stripped-down,

athletic bareness you were expecting, in those days, of any workout space,

and I recall it took a good light through big windows, which made it a

cheerful, energetic place to sweat and shout in.

These recollections are my own, and I may be mistaken, over 40-years

later, about small details, but, anyway, I don't remember a changing room.

I do recall the Master's office because we were taught to bow to it whether

or not he was in it at the time.

There was a heavy boxing bag hanging from the ceiling. The floor, I believe,

was wood. There might have been a few kick targets – shields, no

paddles yet – but no dip-foam chops yet; Master Rhee was still in

the process of inventing much of the gear which was to make tournament

competition on a large scale attractive, practical and safe.

What there were, stored and ready, were big, rattling sheets of used

x-ray plate film about the size of a small movie poster. At first, I couldn't

figure out why.

Not only was there no drink vending machine, you couldn't even get a

drink of water because, Master Rhee pointed out, we were training to fight,

maybe to the death, and you can't stop in the middle of a battle to gulp

a Coke.

So I showed up for my first class and remember my vanity being dinged

because Master Rhee didn't seem particularly glad to see me. He had other

things on his mind. But he explained the rules, the traditional martial

artist's strict code of conduct, and taught me to bow to him and all my

instructors. Then the Master sold me my first light-weight white cotton

dobok. The pants cropped off at the mid-calf length: "high-water

pants," we called them.

After folding the uniform just-so, respectfully, as we were taught, and

then wrapping it with the white belt knotted just-so (square knot, not

a granny knot), the uniform ended up being a neat bundle not much larger

or weightier, it seemed to me, than a big handkerchief. The school patch

we wore spoke unforgettably of "Might for Right."

The Master showed us how the dobok could be slung casually over one shoulder

to carry around by the belt. Also, how you could slip your hand and forearm

inside, to improvise protection if a knife attack overtook you.

He also demonstrated how the belt could be used, to tie up a fist fighter's

arms, or snapped like a whip, to hold off dogs. I thought it said a lot

about war-wracked Korea that holding off hungry dogs could be so uppermost

in my Master's thinking.

Both the Korean and United States' flags were up on one wall, and we

learned to bow to them as we bowed to our Master, instructors, and to

each other. Respect, dignity and discipline were demanded of us. There

were no women and no kids – not yet. Master Rhee pioneered including

both as students in coming decades, along with musical forms, and the

dip-foam gear he invented.

So the D.C. students of 1963 were young men, white and a few blacks,

between mid-teens to late-twenties. No music played. We kiyuped after

every kick, punch, every high, low or middle forearm or knife-hand block;

and you got used to no longer noticing you were always hearing the slip

and slap of bare feet.

It was all about respect. Otherwise, people might get unnecessarily hurt.

Of course, this was Korean martial arts, so getting a little banged up

once in a while was simply in the cards. We lived, without complaint,

by the same code of roughhouse we had learned in the playground.

Class ran about an hour. They worked us to exhaustion. "Hard training

is best training." And we did have, aside from Master Rhee, at least

one other Korean instructor, whose name unfortunately escapes me now,

but the man I remember most vividly was John Dutcher.

John still remains my first image of an American TKD instructor, and

I revere his memory. Years later, they say he disappeared into the jungles

of South America, on a secret mission for the government.

John had a pair of hard hands! We all did knuckle pushups, of course.

And everybody trained relentlessly on a canvas-covered makiwara nailed

to a two-by-four rooted in the floor in such a way that it gave a little

when you hit it with knuckles and knife-hand. We were toughening up for

the hard breaking which, since Oyama, had been synonymous with "karate."

To hear him, Dutcher had the mildly-spoken but slightly angry certainties

I associated with military men. Whatever he said to do, we did it immediately

and flat-out. Everything came down to basics. Long stances, a shoulder's-width

between your feet, step into a right reverse punch, then into a left reverse

punch, keep the feet the right distance apart, at the end turning around

correctly, marching up and down, kiyuping up and down the second-story

room.

The instructors occasionally hit us with long sticks when our form was

bad. I can't say they clubbed us, not at all, but it certainly did help

you grasp the seriousness of small details when performing the basic punches

and kicks.

I can remember my shocked awe the first time I saw the Master do a simple

side kick. Rhee's remains in my mind as one of the purest, most powerful

kicks I've ever seen. He seemed to coil up, to gather every ounce of body

weight and muscle power, and then unleash it in a textbook-perfect strike

that impressed a rank amateur as able to kill a man.

Of course, the very idea of kicking your opponent was a slightly-shocking

revelation to us. For one thing, Roy Rogers had taught us that kicking

was unmanly and "fighting like a girl." On the other hand, nobody

in my class had ever seen such devastating leg moves before.

Remember, next to nothing had been shown on TV, and you for-sure saw

no karate movies. (It was only the year before, in 1962, that the first

American motion picture karate fight was filmed for "Manchurian Candidate;"

and Frank Sinatra actually did break his little finger while fighting

Hispanic Henry Silva, who was playing... a Korean.)

Learning how to kick, then, was the most difficult thing I ever had to

do, even with the x-ray plates for targets. Because, yes, that was what

those big, flimsy, brittle photographic negatives were used for.

When you hit them right, they gave off a nice, crisp sound that implied

you were getting better at chambering back the knee and shooting out the

leg, your foot held with the heel higher than the toes and always aiming

to hit with the heel, except for the round house, when half the time you

curled back your toes and struck with the ball of the foot.

Even in those days, Master Rhee was using his school as a good reason

to invite to visit the USA, for a few weeks, Korean kids who were champions

back home. He chose serious, educated, cheerful guys who gave every indication

of someday being lawyers, businessmen and politicians.

They received the cosmopolitan advantage, as future Korean leaders, of

having spent some time among Americans in our Nation's Capital. And we

the students were inspired by authentic TKD heroes, capable of even such

jaw-dropping spectacles as doing full splits. I didn't know a male could

do such a thing.

Once, one of these young Korean champs, a great guy we all admired, set

up a "problem" to solve by positioning five of us while we each

held x-ray film. He spun through us like a tornado – it happened

too fast to take-in when you still didn't always know what you were looking

at – and all I remember was bits and pieces of kick-shattered x-ray

film fluttering down all over the floor. If he had walked on the ceiling,

I couldn't have been more impressed.

By inviting these Korean champions here, I first glimpsed Master Rhee's

lifelong determination to use TKD for the good of, not just his students,

not only for our community, but the entire world, in the global world

he saw coming, where we all needed to understand each other better.

That summer, I took my first martial arts promotional test, for green

belt. There were, in fact, only white, green, blue, brown and black ranks.

I did my basic form (could there have only been one?; there were only

a few, simple kicks, too, no XMA yet!, so I suppose it's possible), the

line drills, the front and hip-torqued side and round house kicks. The

board breaking.

As a self-conscious young TV personality, I recall being sure I'd performed

terribly. Maybe so, but any instructor could have told at a glance that

my heart and soul were put into my test. I was hooked, I was claimed.

To my great surprise and deep satisfaction, I received my green belt.

In those days, your instructor tied it on you, personally, the first time

you wore it.

That fall, I left DC to go to Charlottesville for my freshman year at

The University of Virginia. One day, early into the first term, I wore

my dobok into the University's indoor athletic facilities. I claim to

this day to have been the first American guy to wear one "on the

grounds."

Last year, I was among the invited guests up on the third floor of Tony

Cheung's famous D.C. Chinatown restaurant, when Willy Lin publicly passed

along his tien shan pei Grand Master's rank to Dennis Brown. Grand Master

Rhee was there, and I went over to bow and shake hands.

His hair is no longer so raven's-wing black; the face, although older

and wiser, still shows through it the extraordinary spirit within.

"You changed my life, kwanjanim," I told him.

"I only did one percent," he answered. "You did the rest."

No, I thought in my heart of hearts, I just stumbled as best I could

in the wake of your example. And if I ended up a competent martial artist,

it is because once I brushed up against such genius.

Herb Borkland is a veteran black belt and martial arts writer living

in Columbia, Maryland.

About The Author:

Washington, D.C. native Herb Borkland has been called "a

martial arts pioneer" because he was an original student at the first

taekwondo school in the United States. After taking his degree at The

University of Virginia, Herb went on to become a closed-door student of

the legendary Robert W. Smith, author of the first English-language book

about tai chi. An Inside Kung-Fu Hall of Fame writer, he was the first

journalist ever invited to train in SCARS, the Navy SEALs fighting system.

Herb scripted "Honor&Glory" for Cynthia Rothrock, featured

on HBO, as well as winning the first-place Gold Award at the Houston International

Film Festival for his Medal of Honor soldier screenplay "God of War."

For three years he hosted the national half-hour Black Belts cable-TV

show. Herb and his wife, the Cuban-American painter Elena Maza, live in

Columbia, Maryland. |