The Benefits Of Solo Iaido Practice

By Deborah Klens-Bigman, Ph.D

Editor’s Note: The Japanese art of iaido is the modern discipline

or way of drawing the sword that assumed its present form in the early

20th century.

We have a student who has been with us for some time, who hates to practice

alone. This time of year, when dojo attendance is generally sparse, I

have sometimes arrived for practice to see him still not dressed, "waiting

for someone else to show up."

"What would you do if no one else came?" I asked.

"I'd go home. I hate practicing by myself."

Forget that the studio rent is already paid, regardless of who might

show up. No one to practice with, go home. It seems logical until you

look at all the benefits of solo iaido practice.

|

The author practices alone

in Mamiyana Park,

Toyko, 1986. Photo by David Dougherty.

|

While there are partner exercises in sword practice,

for example the Tachi Uchi no Kurai in Muso Shinden Ryu iaido, 80% of

the curriculum

is solo forms. Though they are brief in terms of length of time, there

are about 43 solo kata (depending on how you count them) as opposed to

about ten partner forms. While all the solo forms have bunkai (applications)

which can be practiced with a partner, most iai kata practice is done

individually. In Japan, individuals often practice a particular form

under the supervision of senior students and the teacher, who walk around

the dojo and give personal instruction, either correcting a form or teaching

a new one to a lower-ranked student. Senior students, in turn, may have

a similar practice experience under the supervision of the daisen'pai

(most senior student) or teacher.

|

|

You can learn a

lot of technique at a seminar, but you don't have much time to

think about it. Pam Parker teaches

a seminar at New York's Ken Zen dojo, 1997.

Photos by Deborah Klens-Bigman. |

Western martial arts classes tend to emphasize uniform movement. Frederick

Lohse (1999) suggests the uniform movement and almost military character

of some American martial arts dojo may derive from the teachers' experience

in military training and service overseas rather than their original

dojo experience in Japan. Some U.S. dojo encourage harmonious movement

to allow a maximum number of people to work out within a confined space.

It is impressive to see a tightly-packed group of senior students practicing

together with a highly developed sense of both ma (space/time) and wa

(harmony). Some dojo simply adopt the "seminar model" of visiting

teachers who encourage a uniform workout to impart the greatest amount

of material in the shortest time to the largest possible group of participants.

With the limited amount of practice time in a given week, practice by

the group as a whole is considered the most efficient means to an end.

Whatever the reason, individualized solo practice during "official" class

times is not particularly encouraged or seen here, which is too bad.

There is a lot of benefit, not only in individual instruction, but in

practicing on one's own as well.

For my part, the best practice time, in order of fun is: (1) myself

and the senior instructor, (2) myself alone, and (3) myself and the next-ranked

person below me, or, failing that, a single, promising beginner. Not

that I don't enjoy teaching beginners, or even working with the group,

but that isn't what I signed up for all those years ago. I signed up

to practice iaido.

Solo iai practice can be accomplished in a number of ways, not all of

which even involve putting on your keikogi (practice uniform) and breaking

an actual sweat. Reviewing a written outline of forms allows you mentally

to "rehearse" a set of forms (even partner forms) as well as

accomplishing such mundane goals as learning the proper names for the

kata. Having gone through that process, it is possible to review the

actions of a form in your head while waiting for a bus or during some

other low-key activity. Especially if an outline is not available, taking

the time to write a description of a form is an exercise in memory and

increased understanding (the more so if you refer back to it from time

to time). As to physical practice, it can be as simple as picking up

a bokuto (practice sword) in your home for a few minutes a day to review

basics, or a full-blown private session. In space-starved New York City,

it is often easiest to rent a studio for an hour rather than endanger

the contents of a cramped apartment. An hour seems brief, but if you

are ready to start at the top of the hour and work continuously, you

can accomplish a lot. It takes some effort and a little cash, but the

results are worth it. Anything you have time to do seems invariably to

result in improvement (few things in life are that gratifying). My teacher

Mr. Otani used to say anyone with ten minutes a day can learn iaido.

It took me many years to understand that statement, but now I think I

do.

It's important to point out that solo practice should absolutely not

be considered the province of senior students. If you are doubtful about

your basics as a beginner, search out a more senior member who practices

on the side and offer to share studio rent with him or her. As long as

you don't pester too much, she should be pleased to have the company.

I would even suggest that you cannot get to be a senior student (of anything)

without solo practice. It is never too early to begin examining your

own practice. The best beginning students I've ever had show marked improvement

from one class to the next. They got that way because they took the time

during the week to go over what we did before the next class. As one

martial arts teacher once pointed out to me, "Practice is free."

Here are some of the benefits of solo practice. There are others, but

I tried to pick out what for me are the major ones:

First, working out alone increases technical understanding of the form

at hand. This is the old "learn at your own pace" adage. I

have never really "learned" a new form in group practice. I

need time to work on it and digest it on my own. As our Chief Instructor,

Phil Ortiz, has said many times, you need to "own" the kata

in order to really know it. The path to ownership is solo practice.

Secondly, practicing alone forces the iaidoka to observe her own actions.

This can sometimes be difficult; not just actually to "see" what

you are doing, but to assess it. Self-observation not only allows you

to see your form, it makes you better at observing the actions of others.

As teachers too numerous to mention have pointed out, one observes others

not necessarily with the idea of correcting them (depending on your rank,

you may or may not be expected to do that), but allows you to reassess

your own practice as the teacher corrects someone else. Asking "Where

in my practice am I also making that mistake?" is a key to improving

your technique.

|

|

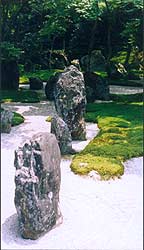

Meditative contemplation seems easy at the 400-year-old

Zen garden at Komyoji, Dazaifu, Japan. It is also the point of solo

practice. Photos by Deborah Klens-Bigman. |

Solo practice forces the iaidoka to employ self-criticism and correction.

No one wants to be self-critical - we just hope we can get away with

stuff in front of other people. Unfortunately, in our dojo at least,

this is never really possible. While the kohai (newer students) may

miss things, the Chief Instructor almost never does. Self-criticism

helps detect and alleviate bad habits, such as leaning forward, or

grabbing the sword rather than drawing it, before the instructor mentions

it to you in class. Believe me, even very experienced iaidoka can make

habitual mistakes. My favorite one is taking one or more fingers off

the saya (sheath) during noto (resheathing the sword), a potentially

very dangerous habit that could result in cutting one or more fingers.

After seventeen years, I still manifest the "errant fingers habit" from

time to time, but by being a close observer of my own practice, I control

this habit better now.

Through self-observation, you can also assess your understanding of

a given form, ask the instructor any questions, and increase your technical

understanding. Better comprehension of the proper execution of a form

obviously improves your practice, and prepares you to instruct others

when the occasion arises.

Solo practice improves concentration, which improves group practice.

This sounds like a paradox, but it is not. Improved concentration gained

by solo practice allows the iaidoka to integrate her practice more easily

with the group. Learning to observe yourself, you can then peripherally

observe others around you. Picking up the timing of the kata, you can

adjust easily to the timing of the group. Orienting yourself to a practice

space alone allows you to "fit in" better with a group, especially

if there is limited room for movement.

Practicing alone allows for insight more easily than in a group situation,

that is, what the form actually means. There is no timetable for this,

though as I have mentioned elsewhere, ten years might be a benchmark.

On the other hand, as I have seen by observing the practice of the above

mentioned reluctant student, insights do not come very much in the context

of a group situation. There is just too much going on at once. Unless

you have a lot of practice by yourself already, a group workout will

remain as filled with insight as a trip to a noisy, sweaty Midtown gym.

I'm still being technical here. "Insight" means understanding

what every little movement in the form means in terms of the bunkai of

that form. Why is there an unusual draw here? Why am I doing this with

the left hand? A teacher may explain it (if you ask, and he feels like

telling you), but you learn a lot more, and value it more, if you learn

it on your own.

Solo practice improves focus and concentration to allow for a more meditative

experience. This seems to be my perpetual theme, but the Buddha didn't

pull his reflection out of the water and contemplate his true self as

a result of attending noisy seminars. He did it after many hours of being

by himself. Iaido and kyudo are perhaps the best vehicles of the Japanese

martial arts for meditative contemplation because of their essentially

solitary nature. Both of these art forms evolved as "-do" forms

with this aspect in mind. Though other "-do" forms (judo, karate-do,

etc.) also have potential as meditative media, iaido and kyudo are predisposed

to individual practice, and, therefore, contemplation.

So, "practice is free," though that same teacher I mentioned

above ruefully pointed out that somehow, perhaps because it is free,

most people will not do it. I had a guy come by to watch our practice

some months ago. He explained to me he was an actor who did stage combat,

and was interested in adding Japanese swordsmanship to his repertoire.

"How long," he asked, "would it take to get a black belt

in this art form?"

This was too much like one of those goofy Zen stories, and I could not

resist.

"That depends on you," I said.

"What do you mean?" he asked.

"I can't tell you," I said. "It depends on your motivation." (Hey,

I took acting class.) "Some people take three years, some more,

some less."

"What if I come to every class? How long would it be then?"

"Practice is free," I said, "as much as you like."

He didn't come back.

About The Author:

Deborah Klens-Bigman is Manager and Associate Instructor of iaido at

New York Budokai in New York City. She has also studied, to varying extents,

kendo, jodo (short staff), kyudo (archery) and naginata (halberd). She

received her Ph.D in 1995 from New York University's Department of Performance

Studies where she wrote her dissertation on Japanese classical dance

(Nihon Buyo), and she continues to study Nihon Buyo with Fujima Nishiki

at the Ichifuji-kai Dance Association. Her article on the application

of performance theory to Japanese martial arts appeared in the Journal

of Asian Martial Arts in the summer of 1999. She is married to artist

Vernon Bigman. For FightingArts.com she is Associate Editor for Japanese

Culture/Sword Arts and is a frequent contributor of articles on iaido

and other topics.

|