Hieho

By John Donohue

Editor's

Note: “Heiho" is the second of two excerpts from

Donohue's new martial arts thriller, "Sensei." The first

excerpt was titled "Intro

To A Thriller" which included the

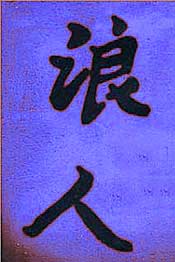

Prologue and Chapter 1 (Ronin) from the book. This excerpt is Chapter

2 from the book. "Sensei" is available in our Estore.

Also read Christopher

Caile's review of this book.

You could usually hear a pin drop in that room. The slanting

rays of the sun came in through the high windows. The angle was acute

enough so that you never had to worry about being blinded (an important

thing in a place where people hacked at each other with oak swords),

but it showed the dust motes dancing around. Less wary students had been

distracted by them. We had all been with Yamashita Sensei for a while,

however, and that morning when he strode onto the floor, all eyes were

riveted on him. You could usually hear a pin drop in that room. The slanting

rays of the sun came in through the high windows. The angle was acute

enough so that you never had to worry about being blinded (an important

thing in a place where people hacked at each other with oak swords),

but it showed the dust motes dancing around. Less wary students had been

distracted by them. We had all been with Yamashita Sensei for a while,

however, and that morning when he strode onto the floor, all eyes were

riveted on him.

Yamashita was a small person: in street clothes he probably would have

seemed surprisingly non-descript. In the martial arts dojo-the training

hall-his presence was a palpable thing. It wasn't just the way he was

dressed. Most of us had been banging around the martial arts world

for years and so were pretty much used to the exotic uniforms. Yamashita

was usually dressed like any other senior instructor in some of the

more traditional arts: a heavy quilted top like the ones judo players

wore and the pleated split skirt/pants known as hakama. The wide legs

of his uniform swished quietly as he knelt in front of the class. Even

in this small action, there was a decisive precision. He gazed at us,

his round head swivelling slowly up and down the line.

Other than his head, nothing moved, but you could almost feel the energy

pulsing off him and washing over you. He was the most demanding of

taskmasters at the best of times, but today we were all tremendously

apprehensive.

Yamashita was wearing white.

In Japan, white is the color of emptiness and humility. Many of us had

started our training in arts like judo or karate, where the uniforms

known as gi were traditionally white as a symbol of humility. Most

mainline Japanese instructors I knew frowned on the American urge to

branch out into personal color statements with their uniforms. The

message was clear: a gi is not a an expression of individuality. People

wanting to make statements should probably rent billboards and avoid

Japanese martial arts instructors. They are not focused on your needs.

They are concerned only with the pursuit of the Way. You are free to

come along. But your presence is not necessary.

You have to get used to that sort of attitude. In the martial arts,

nobody owes you anything, least of all your teacher. The assumption is

that you are pretty much worthless and lucky to be in the same room with

your sensei. You do what he says. You don't talk back. You don't ask

rude questions. You don't cop an attitude-that's the sensei's prerogative.

In the sword arts Yamashita teaches, only the high ranking teachers are

eligible to wear white. Yamashita could. He had done so in Japan for

years. But he didn't do it much here. If he was wearing white today,

it meant that he was symbolically adopting the attitude that he was

the lowliest of students. Humility is nice, of course. The only drawback

here was that, if Yamashita was being humble, it meant that, as his

students, we were somewhere way down in the crud with other lower forms

of life.

As we sat there eyeing him warily, I heard some very quiet sighs up and

down the line: we were in for a rough workout.

You don't get in the door of this particular dojo without having considerable

experience and martial aptitude. In the first place, it's hidden in

Brooklyn among the warehouses down by the East River. We occasionally

have trouble with our cars being broken into and stuff like that, but

then a few us go out and spread the word that Mr. Yamashita is beginning

to get annoyed. He's been in the same location for ten years and has

had a number of"conversations" with the more felonious of

his neighbors-there are people walking those streets whose joints will

never work correctly again.

The neighborhood is dirty and smelly and loud. Once you get inside the

dojo, however, the rest of the world disappears. The training hall is

a cavernous space. The walls are unadorned grayish white and the floor

is polished hardwood. There are no decorations on the walls, no posters

of Bruce Lee or the Buddha. There's a small office area to one side with

a battered green metal desk and two doors leading to the changing rooms.

Other than the weapons racks, that's it. There is absolutely nothing

to distract you from the task at hand. It also means, of course, that

there is nowhere to hide, either.

The sounds of the passing traffic on the Gowanus Expressway are muted.

Half the time, the gasping and thudding and shouts would drown things

out anyway. It's tough inside the building and out.

Yamashita doesn't accept beginning students-we've all got black belts

in at least one art-and you have to have a letter of introduction even

to get an interview. If he accepts you (and he's very picky, relying

on some weird formula none of us really understand) you essentially

get training that makes all the things you endured before pale in comparison.

I've been doing judo for twenty years. I also have another dan ranking

in karate. The first time Yamashita used me as a demonstration partner,

the sheer force of his technique and spirit were overwhelming.

So when I say that the workout was going to be tough, I mean it.

We don't do a great deal of conditioning. What we do is basics.

Yamashita's idea of basics, of course, is bewildering. He thinks basics

are essentially illustrated through application. This is where the

bang and crunch comes in, but with a difference. Anybody can slam someone

into submission-take a look at any tough guy competition or kick boxing

match. Yamashita is after something different. He thinks that the essence

of any particular technique should be demonstrated in its effectiveness.

He doesn't separate form and practicality. He doesn't even admit they

are two separate things. He likes us to destroy with elegance.

There are technical terms for this in Japanese. They can isolate ji-the

mechanics of technique-and ri-the quality of mastery that allows you

to violate the appearance of form yet still maintain true to its essence.

It's hard to explain how they differ and how to separate them, since

most of us have spent years in pursuit of ji and are pretty much conditioned

to follow its dictates. Yamashita doesn't seem to have much of a problem,

however. He prowls the floor like a predator correcting, encouraging,

and demonstrating. And woe to the unlucky pupil whose focus slips during

the exercise: Yamashita screams "Mu ri"-no ri!-and slams

you to the floor.

It's a unique pedagogical technique, but it works for him.

So, beyond the sighs of anticipation, once the lesson started, none of

us spent much time worrying about how tough things were. In the dojo

of Yamashita Sensei, the only way to be is to be fully present and

engaged in the activity at hand. The unfocused are quickly weeded out

and rarely return. The rest of us endure, in the suspicion that all

this will lead to something approximating the fierce skill of our master.

The experience binds you to him in ways I can't even begin to explain.

There's the conscious respect you have for his skills, of course-compared

to him, we're in the infancy of skill development. But there are more

subtle dynamics going on as well. Yamashita knows you. He knows your

weaknesses and fears. He doesn't judge you for them, but he makes you

confront them. In this, he is without mercy. But, if you trust him

enough and can stand the heat of his lessons, you come out changed.

And when that happens, you see the faint ghost of a satisfied smile

drift across his face. It doesn't last long, but in that subtle moment

you feel a pride and a gratitude that keeps you coming back to him

for more.

We were working that day on some tricky techniques that involved pressure

on selected nerve centers in the forearm. At about the time when most

of us were slowing down-shaking our arms out in an effort to get the

nerves to stop jangling-Yamashita called that part of the lesson quits

and picked up a bokken. We scurried to the lower end of the floor and

sat down as he began his instructions.

The bokken is a hardwood replica of the katana-the two handed long sword

used by the samurai. It has the curve and heft of a real sword and

so is used to train students of the various sword arts that have evolved

over the centuries in Japan. Kendo players use something called the

shinai-essentially a tube composed of bamboo strips-in most of their

training. This is because they hit each other with them and don't want

to get hurt.

Bokken, on the other hand, tend to get used in situations where training

is done solo. This is done because, in the right hands, a hardwood

sword can be very dangerous. They have been known to shatter the shafts

of katana and people like the famous Miyamoto Musashi, armed with a

bokken, used to regularly go up against swordsmen armed with real swords.

The results were never pretty, but Musashi used to walk away intact,

bokken in hand.

Bokken are also used in set series of training techniques called kata.

This is typically what Yamashita had us train in with bokken.

Kata means form: they are prearranged exercises. Don't be fooled. Kata

practice in Yammashita's dojo was enough to make your hair stand on

end.

When we perform kata, we do them in pairs of attacker and defender, and

the movements flow and the blade of the bokken moans through the air

as it blurs its way to the target.

There's nothing like the sight of an oak sword slashing at your head

to focus your mind.

I was backpedaling furiously to dodge a slashing kesa-giri-the cut that

with a real sword would cleave you diagonally from your shoulder to

the opposite hip-when movement on the edge of the practice floor caught

my eye.

The visitors filed swiftly in, bobbing their heads briefly in that really

poor American version of bowing. There were three of them in street

clothes and the fourth was dressed in a hakama and top. The outfit

caught my eye: the top was crimson red and looked like it was made

out of some silky sort of material, the hakama was a crisp jet black.

Quite the costume, really, especially when its wearer had a shaved

brown head the shape of a large bullet. He had come to make a statement,

I guess. They sat quietly with their backs against the wall, watching

the class with that hard-eyed, clenched jaw look that is supposed to

intimidate you.

I suppose I should have been impressed, but my training partner would

not let up. She was about as fierce and wiry as they come. And her

sword work had a certain whip and quick snap to it, a slightly off-beat

rapid rhythm that was hard to defend against, even though in kata you

theoretically know what's happening. She wasn't at all impressed with

the visitors. She was a relatively new student who was mostly intent

on making one of Yamashita's senior pupils-me-look less than accomplished.

So even though I was pretty curious about these guys,Yamashita did not,

as a rule, tolerate visitors and one of them was dressed like he came

to play-I quickly got more interested in not making a fool out of myself

during bokken practice.

It's a pride thing. There's a lot of talk in the martial arts about letting

go of your ego and all that, and we try, we really do, but the fact

is that, at this level, you have invested a tremendous amount of time

and effort into developing your skills and creating a certain status

position in the dojo, and you really get just a bit ticked off when

something happens to threaten that. All the bowing and titles, the

uniforms and colored belts, are all about status, your sense of worth.

It's a closed little world with its own system for ranking you, but

it's still a status system, and human beings respond to that.

This woman was good with her weapon. I could sense that and so could

she. She was pressing me a bi-Caltering the tempo of the moves, delivering

her cuts with something close to full force, shortening the time between

parry and counter-delivering a type of challenge to see whether I could

withstand it.

I could, of course, but that wasn't the real point. For me, the challenge

was how to respond to her force with something more refined. It meant

that instead of parrying her cuts with a force that would make our

bokken bark out with the shock of impact, I needed to finesse it a

bit.

I changed the angles slightly, moving my body just out of the line of

attack, which served to place me out of the radius of her strikes.

I tried to keep my hands supple as I parried, accepting the force of

her blows and redirecting them slightly, but things were getting a

bit sweaty and I didn't want the sword flying out of my hands and shooting

across the room. It happens occasionally, and if nobody gets hit we

all laugh and the one who let go gets ribbed unmercifully, but this

was not a situation where I was willing to get laughed at.

I knew this woman was a relative beginner at the dojo, and I counted

on her weapon fixation. It was an unfair advantage in a way, but its

also an example of what Yamashita calls heiho-strategy.

Between shifting a bit and redirecting a bit more through the next series

of movements in the kata, I built up enough frustration in my partner

for her to over commit in her next strike-a little too much shoulder

in the technique, her head leading into it-and it was all over. I simply

let go of my bokken with my left hand, entered into her blind side, led

her around in a tight little circle and took the sword away. It wasn't

a move that was in the kata, but Yamashita tells us any time you can

do tachi-dori (sword taking) to your partner, you should, just to keep

them on their toes.

The pivot took her around on her toes, all right. She knew what was happening

about a split second after the spin began, but it was too late to get

out of it. I handed her back the bokken; she smiled a bit ruefully

and we bowed just as Yamashita called the class to order in preparation

to bow out.

He glided to the head of the room and waited for us to line up. He was

studiously avoiding looking at the gang of four in the back of the room,

but you could tell from his body language that he was annoyed.

You don't come dressed to play unless yove been invited. Only the sensei

can give permission for a student to train in the dojo. If you show

up uninvited and suited up, it means that either you don't know anything

about Japanese martial arts teachers and are in real risk of being

beaten up, or that you are purposefully being insulting and wish to

challenge the sensei to a match.

In which case, it is anyone's guess who gets beat up.

I've seen this happen before. Not often, but you don't tend to forget

it once you've seen it. Especially if you're a student of the teacher

being challenged. You get used as a type of canon fodder for your teacher.

He sends you or one of your pals out to fight the challenger, he watches

the action, analyzes the skill level of the opponent. If the first

student gets beaten, a more advanced pupil goes next, and so on up

the line. By the time the challenger reaches the sensei (if he lasts

that long), he has either revealed his strengths and weaknesses and

so can be defeated, or is so tired that he's no longer much of a challenge

to the sensei. It's not fair, of course. It's heiho.

We all knelt, a solid dark blue line stretching down the length of the

dojo. Yamashita sat quietly for a minute then turned to one of his

senior pupils, a mild-mannered Japanese-American guy named Ken who

sat next to me at the end of the line reserved for higher ranks. He

looked like he was dreading what was about to happen. Yamashita said

to him, "I see we have visitors. Perhaps you would invite the

colorful one to speak with me."

Ken bowed, got up and scurried to the back of the room to deliver the

invitation. The guy in the red top nodded, exchanged a series of ritual

handshakes with his companions and stepped onto the training floor.

He struck a ready pose and let out a loud "UUUS." A few of

us rolled our eyes. Some of the karate schools out there think that

kind of thing makes you seem like a real hard charger.

Yamashita nodded slightly and Red Top moved forward.

"

I regret that I was unable to welcome you properly to my dojo. I am equally

distressed to say that I do not know who you are or what you want, since

we have not been properly introduced." The words came out quickly,

but were carefully pronounced. Sensei doesn't really have much of an

accent, but when he gets annoyed his words get very precisely formed.

I don't know if Red Top was picking it up or not, but there wasn't one

of us who doubted that Yamashita Sensei was really ticked off.

"

Mitchell Reilly, Sensei." He bowed, properly this time. Ken caught

my eye. Mitch Reilly ran a notorious jujutsu school, pretty much specializing

in combat arts of the one-hundred-ways-to-pluck-their eyeballs-out variety.

He was a mainstay of the non-traditional Black martial arts community.

He was built like a refrigerator and I could see his knuckles were enlarged

from the damage too much board breaking creates. Mitch Reilly had the

reputation of being a really savage competitor, a fair technician, and

a guy staggering under the weight of a giant ego.

"

So, Mr. Reilly. I must assume that there is a reason for your presence

here. The school is hard to find and only a man in need of something

would make a journey through such a dangerous neighborhood."

Reilly looked contemptuous. "No problem. I can take care of myself."

"

And," Yamashita continued, "the obvious care with which you

have selected your. . . charming costume tells me that you are, perhaps,

interested in . . . ?" He let the question hang in the air.

I sat and watched the steam start to come out of Reilly's ears. I have

to admit, he got it under control fairly well, which was a sign that

he was probably a dangerous man. When the faint trembling stopped,

Reilly finished Yamashita's sentence.

"A match," he said. "I'm challenging you."

You had to admire him. The guy pulled no punches. He was probably five

years older than I was--in his early forties--and had been banging

around the martial arts for at least two decades, and now felt he was

ready to take on the closest thing the New York area had to a bona

fide master. Most people don't even know Yamashita exists. He came

to New York years ago from Japan for reasons none of us can fathom

and hones our technique with a type of quiet brutality. The senior

Japanese sensei send their most promising pupils to him, but he's never

appeared in Black Belt, hasn't written a book divulging the ancient,

secret techniques of the samurai elite, and doesn=t have a listing

in the Yellow Pages.

Which was why Reilly=s presenceCand his challengeCwas so odd.

You could see Yamashita's quandry. Reilly was fairly dangerous in a savage,

commonplace kind of way. Yamashita was a harsh teacher, but he never

needlessly put any of us in danger of serious injury. It was beneath

Sensei's dignity to accept the challenge, but you could almost hear

the clicks in his brain as he weighed various other options. Would

this match serve any type of purpose in terms of teaching his students?

Who would be the most appropriate opponent? Ken was a senior student

and could be a logical choice. We all knew-and Sensei did too-that

his wife had just had a baby and that a great deal of Ken's mental

energy was not totally focused on training at this time. He was good

(even on his bad days) but a match like this was bound to be one where

both parties limped away. Ken didn't need that right now and Yamashita

knew it.

Yamashita's head swivelled along the line of students, weighing each

one for potential, for flaws, like a diamond cutter rooting carefully

around a draw of unfinished stones. The more experienced among us sat,

trying to be totally numb about the situation, not really focusing

on Reilly, listening to the hum of the fluorescents and the faint rumble

of trucks. The newer students sat in various states: the smart ones

were secretly appalled at the prospect; the really dense were excited.

When he called me, I tried to feel nothing. "Professor," Yamashita

said. Ever since they found out I teach in college, the nickname stuck.

It could have been worse. Early on I had worked out at a kendo school

where the Japanese kids simply called me "Big Head."

I bowed and scooted up to the front. In this situation, you sit formally,

facing the sensei, which put me right next to Reilly

"

This is Dr. Burke," he told Reilly. "I am sure you will find

him instructive."

Reilly jerked his head around to size me up. I looked back; flat eyes,

sitting there like a blue lump with relaxed muscles, no energy given

to the opponent.

"

You think you want a piece of me, asshole?" Out of the side of his

mouth, like he'd picked it up from old Bogart movies. I swung around-you

could see a slight jerk before he realized what I was up to-and bowed,

saying nothing. Silent. Passive. A shade. Heiho was keeping yourself

in shadow.

Reilly looked back at Sensei. "You must be joking. I'm not fucking

around with this piece of shit."

Yamashita is funny about foul language. He spends his days teaching people

how to do serious harm to others, but he has this real thing about

keeping conversation civil. Part of it's just that Japanese politeness,

but I think that the other part is that he is a man dedicated to an

art that celebrates control of one sort or another, and foul language

strikes him as either the result of a bad vocabulary and poor imagination

or as a lack of mastery over your temper. In either case, this kind

of language is forbidden in his dojo. Reilly may not have known it,

but he had just committed a gross breach of etiquette.

"

I am sorry, Mr. Reilly. I regret that we cannot accommodate you in your

request for a lesson. You are clearly not ready for any serious training." With

that, Yamashita looked right through him and stood up like he was preparing

to leave the floor.

"

Wait a minute. . . " Reilly shot up and looked like he was going

to reach for the old man. Which was how I got to wondering about whether

I could pole ax him. I was targeting him for a knuckle strike right below

the ear (I figured with any luck I could dislocate his jaw) but there

was really no need. Yamashita had about reached the limits of his patience.

As Reilly came at him, Yamashita shot in, a smooth blur. There was an

elbow strike in there somewhere before he whipped Reilly around to

break his balance. Then Yamashita was behind him, clinging like a limpet

and bringing Reilly slowly down to the floor. The choke was (as always)

precisely executed: the flow of blood to the brain was disrupted as

he brought pressure to bear on the arteries and Reilly was out cold.

Yamashita stood up and beckoned to Reilly's pals. "Remove him. Do

not come back." Not even breathing hard. They dragged Reilly off

the practice floor and trundled him away.

"

What a foolish man. An arrogant and violent man." He looked around

at us all, then turned to me. "I am surprised at you Burke. I would

have tried for the jaw dislocation. Work on your reaction time, please."

He glided away and the lesson ended.

About the Author:

John Donohue, Ph.D., is a long time kendo practitioner and a black belt

in Shotokan karate who has studied various other Asian martial arts disciplines

such as judo, aikido, iaido, and taiji over the last 25 years. A nationally

recognized authority of martial arts, he is an Associate Editor of the

Journal of Asian Martial Arts and has also written four books involving

the arts: “Herding The Ox”, “Complete Kendo”, “Deshi:

A Martial Arts Thriller” and “Sensei.” Donahue has

also been a featured speaker at national and international conventions,

as well as on radio and TV. For FightingArts.com he has contributed an

in depth article on kendo. A Ph.D. in Anthropology, Donohue is a Professor

of Social Science and VP for Academic Affairs at D'Youville College in

Buffalo, NY. Previously he was a Professor of Social Science in the Department

of Social Sciences at Medaille College, Buffalo, NY, where he also served

as a tenured professor, teaching anthropology, General Education, and

other courses in both undergraduate and graduate programs. He lives in

Youngstown, New York with his wife, the artist Kathleen Sweeney, and

their two children.

Sensei is available in the FightingArts.com Estore

“Sensei”

By John Donohue

(258 Pages, Hardbound)

FSM-BK-1000

$23.95

(Plus $5.00 Shipping Within US)

|