The Beginnings of Kodokan Judo,

1882-1938

By Paul McMichael Nurse, Ph.D.

It

is sad to think about but the first Asian fighting system to gain worldwide

acceptance has been -- for the most part -- relegated by much of the public

and many of its practitioners to the category of a mere sport, a form

of jacketed wrestling of no real value as a combative art and little worth

beyond that of a recreational activity. It

is sad to think about but the first Asian fighting system to gain worldwide

acceptance has been -- for the most part -- relegated by much of the public

and many of its practitioners to the category of a mere sport, a form

of jacketed wrestling of no real value as a combative art and little worth

beyond that of a recreational activity.

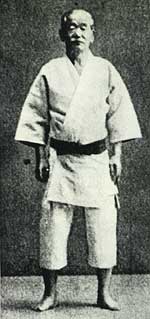

This art, discipline, sport, recreation -- and for many, a way of life

-- is, of course, Kodokan Judo, a modern budo (a generic term referring

to modern martial arts) form founded by the Japanese educator Jigoro Kano

over 100 years ago as a means of instilling physical and moral education

in Meiji-era Japanese youth. Since those first fledgling days in the late-nineteenth

century, judo (the way of flexibility) has grown to become one of the

most popular activities on earth. Over 8,000,000 people in Japan practice

it regularly, with another 3,000,000 followers worldwide. Judo's debut

as a sport in the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games has further cemented its status

as a truly international endeavor.

Gratifying as these figures are, it is nevertheless well to remember

that judo's success as a sport lies outside its founder's original intentions,

and that shiai, or tournament contest, was in many ways the least important

of Kano's objectives. Thus it is perhaps well to pause and re-examine

the origins of Kodokan Judo, for by returning to the source of the art

we may rediscover what is in great danger of being lost.

Jigoro Kano was born October 28, 1860, the third son of a well-to-do

merchant family in Kobe, in Hyogo Prefecture. As a youngster Kano was

highly intelligent but sickly and physically underdeveloped, and thus

a favorite target of school bullies.  To

strengthen his physique and deal with the bullying he began an intensive

program of physical exercise, participating in gymnastics, baseball, rowing

and hiking. Within two years his health had markedly improved - so much

so that at the age of seventeen he began the study of Tenshin Shinyo ryu

jujutsu (a modern offshoot of the Edo Period Yoshin ryu, or tradition)

under Hachinosuke Fukuda. As a jujutsu system the Tenshin Shinyo ryu was

noted for its striking techniques (ate-waza) and katame-waza (grappling

techniques). To

strengthen his physique and deal with the bullying he began an intensive

program of physical exercise, participating in gymnastics, baseball, rowing

and hiking. Within two years his health had markedly improved - so much

so that at the age of seventeen he began the study of Tenshin Shinyo ryu

jujutsu (a modern offshoot of the Edo Period Yoshin ryu, or tradition)

under Hachinosuke Fukuda. As a jujutsu system the Tenshin Shinyo ryu was

noted for its striking techniques (ate-waza) and katame-waza (grappling

techniques).

Fukoda's death a few years later, as well as that of his successor, Masatomo

Iso, prompted Kano to transfer to the Kito ryu under Tsunetoshi Iikubo.

Unlike the Tenshin Shinyo ryu, the Kito ryu emphasized nage-waza, or throwing

techniques, and laid stress on abstract symbolism in addition to the physical

aspects of the art. Kano's exceptionally tattered uwagi (training jackets)

used during this period, are today among the Kodokan's most treasured

artifacts -- mute testaments to the vigor with which the young man approached

his jujutsu training. Although he had many injuries, Kano persevered with

characteristic determination and eventually gained some proficiency in

both systems.

At this time jujutsu (the art of limberness) had something of a bad reputation

within a Japan which was rapidly modernizing to compete with an industrialized

West. The loss of status among disenfranchised bushi (samurai) forced

many former members of the warrior class to teach their arts to any and

all who could pay for lessons. A number of these were rough types looking

to prey on the weak and helpless, and thus jujutsu gained an undeserved

reputation as a practice of the lower sorts of society.

Kano, however, knew firsthand the benefits jujutsu practice had provided

him and what social gains might be had by correct training in combative

arts. Disturbed by public opinion regarding jujutsu, as well as by what

he considered dangerous practices within jujutsu itself, he resolved to

do something about it. To this end he undertook an intensive examination

of the unarmed systems he had actively studied, as well as an academic

study of many others, especially the unarmed combat methods of classical

bujutsu (ancient martial traditions) such as the Sekiguchi ryu and Seigo

ryu. He came to the conclusion that not only did jujutsu have a bad reputation

within Meiji society, but the study of jujutsu itself was often dangerous

to the participants since it contained many kicks, strikes, joint locks

and pain-holds which often resulted in injury and the occasional death.

Nevertheless, Kano believed that with changes, training in jujutsu-style

techniques could prove advantageous in the physical and moral development

of people of high character, especially Japan's youth who would comprise

the next generation.

At the same time that he was developing his notions of a reformed jujutsu,

Kano was a student at the Tokyo Imperial University, studying literature,

politics and political economy. He graduated in 1881 and the following

year became an instructor at the prestigious Gakushuin, or Peersí

School, in Tokyo, a school for children of the nobility. Kano continued

his lifelong involvement with academic education, earning a doctorate

and eventually becoming Headmaster of the Tokyo Teachers' Training School.

The same year that Kano became an instructor at the Gakushuin, he was

ready to begin teaching his brand of jujutsu.

He decided to call his system Kodokan Judo, "the place for studying

the way of flexibility," deliberately employing the already-extant

word judo because he wished to differentiate his system from the bad odor

surrounding jujutsu. Starting with just nine students on a twelve tatami

mat area at the Buddhist Eishoji Temple in the Shitaya area of Tokyo,

the formal date of the founding of the first Kodokan was June 1882.

During these early days all judo practitioners (judoka) were required

to place a seal of blood on an open register and declare five oaths:

1) Upon admittance to Kodokan, I shall not discontinue my judo study

without good reason.

2) I shall not bring dishonor to the dojo.

3) I shall not tell or demonstrate the secrets I have learned to anyone

without authorization.

4) I shall not teach judo without authorization.

5) First as a student, and later as an instructor, I will always obey

the dojo rules.

Sometime the following year (1883) Kano initiated a kyu/dan (ungraded/graded)

ranking system within Kodokan based on the concept of colored belts worn

by participants. For the first three grades students wore a white belt

or sash, while for the next three grades he wore brown. All these kyu

levels were considered mudansha (literally unranked; mu coming from the

Japanese word for "nothing") before the student became yudansha

(holder of rank) -- a so-called "black belt," although only

the first five yudansha ranks (dans) actually wear a black belt. Six,

seven, and eighth dans wear a sectioned red-and-white belt, while ninth

and tenth grades wear a solid red belt. It might be noted that (the only

exception to normal ranking) Dr. Kano was awarded a posthumous twelfth

dan consisting of a novice's white belt, but twice the width of average

ones -- an indication that one of judo's main concerns and themes is circularity.

Kano's kyu/dan and belt system, as well as adoption of standard uniforms

(which evolved over time) initially gave judo recognition. They were later

adopted by other budo forms, such as kendo, aikido, karate-do, as well

as many other systems from around the world. Unfortunately, the ranking

and belt system has become fragmentized with addition of other colored

belts and even stripes on colored belts to the point that meaning has

been lost.

In terms of technique, however, Kano was not so much a great inventor

or originator of a fighting form as he was a great synthesizer, a figure

who masterfully took various aspects of other systems and blended them

into a new whole. Perhaps his greatest innovation were the teaching of

ukemi, or "breakfalling," before a new student begins the study

of technique. This ensures that when a novice is thrown, he or she has

already learned how to land safely and efficiently on the mats without

danger. This was a significant departure from many of the jujutsu systems

Kano had examined previously, where students were thrown -- sometimes

having their limbs deliberately wrenched in the bargain -- and had to

land as best they could.

Certain techniques such as dojime (leg-scissoring around the abdominal

region with the thighs), which Kano deemed too dangerous, were also removed

from the Kodokan curriculum. Also matches were begun by opponents stepping

forward and grasping each others judogi (training suit) in a prescribed

manner before commencing free practice (randori). However, some of what

Kano excised from the general Kodokan syllabus were kept for the study

of certain kata (prearranged forms), or as special study for higher grades.

Kano's precepts for judo are contained in two founding principles he

developed during his career: Seiryoku Zenyo, the "Principle of Efficient

Use of Energy," and Jita Kyoei, or the "Principle of Mutual

Welfare." A Kodokan disciple was enjoined to strive to attain the

best manner of his physical and mental energy in both judo and everyday

life, as well as to have a sincere consideration for others. Stress was

placed on education and moral development rather than the concentration

on pure technique lying at the heart of most jujutsu systems. To this

end only those applicants with impeccable characters were permitted to

join Kodokan; in its original structure it was emphatically not developed

to be taught indiscriminately to everyone.

For the first few years of its existence Kano's system fought something

of a rear-guard action against the decaying jujutsu systems. Many are

the tales in Kodokan lore of how Kano's students had to defend themselves

and their art from disciples of other, more established budo schools who

challenged the upstart Kodakan. In particular, a hot rivalry developed

between Kano's school and jujutsu master Hikosuke Totsuke and his resurgent

Yoshin ryu.

A crucial test came in 1886. The Tokyo Police Department Board, casting

about for a system of unarmed combat with which to train their forces,

sponsored a tournament between these two leading ryu to decide which to

adopt. Failure against the Yoshin ryu could conceivably sound the death-knell

for Kano's judo. Fifteen men were selected to represent each side. The

result was a brilliant triumph for the Kodokan. Led by judo legends Sakujiro

Yokoyama and Shiro Saigo, Kano's group won all but one of the matches

and that was deemed a draw (some sources indicate that thirteen matches

were won and two were draws). With this victory judo's reputation as an

efficient system of unarmed combat was assured and the art became officially

sanctioned by the Japanese government.

Judo's popularity grew so rapidly that by the early twentieth century

many jujutsu systems, fearful of falling into abeyance, merged with the

Kodokan -- as much for the preservation of their techniques as an acknowledgment

of Kodokan's ascendancy. Their inclusion injected a number of new waza

into the Kodokan system, which continued to develop until July 1906 when

Kano and a gathering of jujutsu masters met at the Butokuden (Martial

Virtues Hall) in Kyoto to formulate modern kata and finalize the judo

syllabus. Within a relatively short time judo, along with kendo (the art

of fencing with mock swords), became popular activities at Japanese universities,

inducing the Japanese Ministry of Education to include both arts as required

parts of the school syllabus (1911), a position they retain to this day.

At the same time, not all jujutsu ryu accepted Kodokan's supremacy and

strived to keep judo (by now the word had gained general acceptance as

a virtual synonym for jujutsu) more of a combative art. In Kansai Prefecture

a movement developed, especially centered in the Butokuden and supported

by the Dai Nippon Butokukai (All Japan Martial Virtues Society, founded

in 1895), toward retaining some of the techniques that Kano had discarded

in the formation of his system. A number of techniques, particularly of

the pain-hold variety rejected as too dangerous for Kodokan students,

were retained, as well as a distinct emphasis on katame- waza (grappling

techniques on the ground) as opposed to the emphasis on nage-waza within

the Kodokan system. It should be stressed that this Kansai brand of judo

(one occasionally reads of it described as "Budokan Judo," but

this is an inadequate translation) was not considered a distinctly separate

system or tradition of judo, but was viewed more as a stylistic rival

of Kodokan -- a "country cousin," so to speak, of the Kanto

variety (Kanto is the prefecture where Tokyo, and the Kodokan, resides).

Evidence of this may be seen in the fact that Kansai yudansha ranks issued

by the Butokukai up to and including nidan (second-grade) were accepted

without question on application to the Kodokan in Tokyo, but those students

wishing recognition from Kodokan regarding higher ranks had to undergo

rigorous scrutiny by Kodokan authorities to ensure that their technical

proficiency was sufficient. By 1907 the movement had a significant following

in colleges and technical schools, but did not survive the end of the

Second World War.

Technically, judo's "Golden Age" may be said to have been the

period between World War I and World War II.. During this time the art

reached a state of technical excellence it has not approached since. Although

contest participation was considered part of judo training, the activity's

ne plus ultra was considered to be seishin tanren, or "spirit-forging"

Here the practice of judo was the vehicle by which students advanced themselves

spiritually through rigorous physical discipline.

Kano never intended his system to become merely a sporting contest, but

it was perhaps inevitable that as judo became ever more popular with the

public at large, shiai would likewise take on popular dimensions. During

the 1920s the most prestigious tournament was the Emperor's Cup, open

to all judoka who were subjects of the Japanese Empire. The first "All-Japan"

Championships were inaugurated in 1930 and lasted until the outbreak of

the Pacific War. As with today's All-Japans there were no weight categories;

contestants were divided into Young Men's (under thirty years of age)

and Senior or Master's division above thirty. Elimination was of the simplest

form: one loss and the contestant was out. Thus the eventual champion

was always undefeated. Contestants were required to win by two full points,

either by double ippon (one full point, gained by a clean throw) or the

equivalent cumulative half-points (wazari). The current method of decision

by fractured points would have been anathema to these old-time practitioners,

who put their hearts and souls into defeating their opponents by the best

possible technique -- the judo equivalent of a boxing knockout.

Kano's ardent desire to gain worldwide acceptance for his system resulted

in his undertaking a number of foreign journeys to promote judo at the

international level. During one of these sojourns, in London in 1933,

Dr. Kano spoke of his desire for a world judo federation and the dissemination

of Kodokan Judo teachings throughout the world as a means of aiding in

achievement of world peace. Already he had become Japan's first representative

on the International Olympic Committee (1909), as well as the first president

of the newly formed Japanese Amateur Sports Association (1911).

But the warlords of Europe and Asia were in the ascendancy during this

period, and Kano's dream of a Tokyo Olympic Games in 1940 wherein his

beloved judo would be a demonstration sport was never realized. Returning

from an International Olympic Association conference in Cairo in the spring

of 1938, Kano fell ill with pneumonia aboard the ship Hikawa Maru. On

May 4, 1938, at age seventy-eight, he died at sea between Vancouver and

Yokohama. It is perhaps as well that he did not live to see the defeat

of Japan in 1945 and the subsequent prohibition of judo and a number of

other combative arts during the period of Allied occupation (1945-52).

The great educator's dream of an international judo movement was merely

deferred, however, not dead. In 1952 the International Judo Federation

(LIF) was formed from the European Judo Union (IJU) to promote and regulate

judo throughout the world; by the Kodokan's centenary (100 year's ) celebrations

in 1982 it had more than seventy member nations. The first World Championships

were held in Tokyo in 1956, followed by a repeat hosting in Tokyo in 1958

and then Paris in 1961, where the Dutch giant Anton Geesink became the

first non-Japanese world champion. At long last judo made its debut in

the 1964 Tokyo Olympics to a tremendous reception. Except for the 1968

Games in Mexico City, it has been a featured sport of every Olympics since.

Truthfully, however, judo's internationalization as a competitive sport

is something of a mixed blessing. Certainly Dr. Kano's vision of an international

judo organization has come to be realized, but at the cost of many of

his educational aims. Classical Kodokan Judo is a system of physical training

leading to improved individuals; originally, training was to be evenly

divided between kata, randori, and shiai, with supplemental lectures on

judo principles and other matters for students' edification. Contests

were considered only a part of training, and decidedly were not the primary

objective. Whatever their reasons for studying judo, today's practitioners

could benefit from keeping their founder's ideals in mind.

About The Author:

Paul McMichael Nurse has a Ph.D. in History from the University of Toronto

and a researcher and writer on judo and other martial arts. His articles

have appeared in Kick Illustrated and Black Belt Magazine. He is also

a member of the International Hoplology Society (the academic study of

combative systems) and has been a student of judo, he says, "sporadically,"

since 1969.

|