Channan: The "Lost" Kata of Itosu?

By

Joe Swift By

Joe Swift

Introduction

The series of five basic kata called Pinan (later renamed Heian in Japan)

are probably the most widely practiced kata in karate today. It is commonly

understood that they were developed by Anko (or Yasutsune) Itosu (1832-1915)

in around 1907 for

inclusion in the karate curriculum of the Okinawan school system. However,

the actual history of the Pinan series has been the subject of intense

curiosity as of late. There are basically two schools of thought, one

that Anko Itosu (1) developed them from the older classical forms that

were cultivated in and around the Shuri (capital of Okinawa) area, and

the other that Itosu was re-working a longer Chinese form called Channan.

Unfortunately, most of the written references to the Channan/Pinan phenomenon

in the English language are basically re-hashes of the same uncorroborated

oral testimony. This article will examine the primary literature written

by direct students of Itosu, as well as more recent research in the Japanese

language, in an effort to solve the "mystery" of Channan.

Anko Itosu

In order to understand the Pinan phenomenon, perhaps it is best to start

off with a capsule biography of their architect, Anko Itosu (1832-1915).

Many sources state that Itosu was born in the Yamakawa section of Shuri

(Bishop, 1999; Okinawa Prefecture, 1994; Okinawa Prefecture, 1995), however,

noted Japanese martial arts historian Tsukuo Iwai states that he was actually

born in Gibo, Shuri, and later relocated to Yamakawa (Iwai, 1992). He

is commonly believed to have studied under Sokon ("Bushi") Matsumura

(1809-1901), but also appears to have had other influences, such as Nagahama

of Naha (Iwai, 1992; Motobu, 1932), Kosaku Matsumora of Tomari and a master

named Gusukuma (Nihon Karate Kenkyukai, 1956).

There does not seem to be much detail about Itosu's early life, except

for the fact that he was a student of the Ryukyuan civil fighting traditions.

At around age 23, he passed the civil service examinations and was employed

by the Royal government (Iwai, 1992). It seems as if Itosu gained his

position as a clerical scribe for the King through an introduction by

his friend and fellow karate master Anko Asato (Funakoshi, 1988). Itosu

stayed with the Royal government until the Meiji Restoration, when the

Ryukyu Kingdome became Okinawa Prefecture. Itosu stayed on and worked

for the Okinawan Prefectural government until 1885 (Iwai, 1992).

There is some controversy as to when Itosu became a student of Matsumura.

Some say that he first met Matsumura when Itosu was in his late 20s (Iwai,

1992), whereas others maintain that Itosu was older than 35 when he began

studying from Matsumura (Fujiwara, 1990). Matsumura appears to have been

friendly with Itosu's father (Iwai, 1992).

Be that as it may, Itosu is said to have mastered the Naifuanchi kata

(Nihon Karate Kenkyukai, 1950; Okinawa Pref., 1995). In fact, one direct

student of Itosu, namely Funakoshi Gichin, recalled 10 years of studying

nothing but the three Naifuanchi kata under the eminent master (Funakoshi,

1976) (2).

Again, there is some controversy as to where Itosu learned the Naifuanchi

kata. Some give credit to Matsumura for teaching this kata to Itosu (Murakami,

1991). However, others say differently, and here is where we first start

to see reference to Channan, as the name of a person. It is said that

a Chinese sailor who was shipwrecked on Okinawa hid in a cave at Tomari.

It was from this man that Itosu supposedly learned the Naifuanchi kata,

among other things (Gima, et al, 1986).

In either case, it is known that Itosu was among the first to teach karate

(toudi) publicly, karate having previously been taught and practiced in

secrecy for hundreds of years. Itosu began his public teaching pf karate

as physical education in the school system as early as 1901, where he

taught at the Shuri Jinjo Primary School (Iwai, 1992; Okinawa Pref., 1994).

He also went on to teach at Shuri Dai-ichi Middle School and the Okinawa

Prefectural Men's Normal School in 1905 (Bishop, 1999; Okinawa Pref.,

1994, 1995).

In addition to his "spearheading a crusade" (McCarthy, 1996)

to modernize toudi practices and get it taught in the school system, Itosu

was also known for his physical strength. It is said that he was able

to crush a bamboo stalk in his hands (Funakoshi, 1976, 1988), once wrestled

a raging bull to the ground and calmed it (Nagamine, 1986) and one could

strike his arms with 2-inch thick poles and he would not budge (Iwai,

1992).

Itosu's unique contributions to the art of Karate-do include not only

his 1908 letter to the Japanese Ministry of Education and Ministry of

War (3), expounding on the 10 precepts of Toudi training, but also the

creation of several kata. These include not only the Pinan series, but

also Naifuanchi Nidan and Sandan (Kinjo, 1991; Murakami, 1991), and possibly

Kusanku Sho and Passai Sho (Iwai, 1992). Another kata that has often been

attributed to Itosu is the Shiho Kusanku Kata (Kinjo, 1956a; Mabuni et

al, 1938), but more recent evidence points to the actual originator of

this paradigm to have been Mabuni Kenwa himself (Sells, 1995).

In addition to creating several kata, the other kata that Itosu taught,

such as Chinto, Useishi (Gojushiho), Passai Dai, and Kusanku Dai, etc.,

were changed from their original guises, in order to make them more palatable

to his physical education classes (Kinjo, 1991).

Itosu Anko passed away in March 1915, leaving behind a legacy that very

few today even recognize or comprehend.

Early Written References to Channan and Pinan

References to Channan can be found as far back as 1934. In the karate

research journal entitled Karate no Kenkyu, published by Nakasone Genwa,

Motobu Choki is quoted referring to the Channan and the Pinan kata:

"(Sic.)

I was interested in the martial arts since I was a child, and studied

under many teachers. I studied with Itosu Sensei for 7-8 years. At first,

he lived in Urasoe, then moved to Nakashima Oshima in Naha, then on to

Shikina, and finally to the villa of Baron Ie. He spent his final years

living near the middle school. "(Sic.)

I was interested in the martial arts since I was a child, and studied

under many teachers. I studied with Itosu Sensei for 7-8 years. At first,

he lived in Urasoe, then moved to Nakashima Oshima in Naha, then on to

Shikina, and finally to the villa of Baron Ie. He spent his final years

living near the middle school.

I visited him one day at his home near the school, where we sat talking

about the martial arts and current affairs. While I was there, 2-3 students

also dropped by and sat talking with us. Itosu Sensei turned to the students

and said 'show us a kata.' The kata that they performed was very similar

to the Channan kata that I knew, but there were some differences also.

Upon asking the student what the kata was, he replied 'It is Pinan no

Kata.' The students left shortly after that, upon which I turned to Itosu

Sensei and said 'I learned a kata called Channan, but the kata that those

students just performed now was different. What is going on?' Itosu Sensei

replied 'Yes, the kata is slightly different, but the kata that you just

saw is the kata that I have decided upon. The students all told me that

the name Pinan is better, so I went along with the opinions of the young

people.' These kata, which were developed by Itosu Sensei, underwent change

even during his own lifetime." (Murakami, 1991; 120)

There is also reference to Pinan being called Channan in its early years

in the 1938 publication Kobo Kenpo Karatedo Nyumon by Mabuni Kenwa and

Nakasone Genwa. Mabuni and Nakasone write that those people who learned

this kata as Channan still taught it under that name (Mabuni, et al, 1938).

Hiroshi Kinjo , one of Japan's most senior teachers and historians of

the Okinawan fighting traditions, and a direct student of three of Itosu's

students, namely Chomo Hanashiro, Chojo Oshiro, and Anbun Tokuda, wrote

a series of articles on the Pinan kata in Gekkan Karatedo magazine in

the mid-1950s. In the first installment he maintains that the Pinan kata

were originally called Channan, and there were some technical differences

between Channan and the updated versions known as Pinan (Kinjo, 1956a).

Again according to Hiroshi Kinjo, Hisateru Miyagi, a former student of

Itosu who graduated from the Okinawa Prefectural Normal School in 1916,

stated that when he was studying under the old master, Itosu only really

taught the first three Pinan with any real enthusiasm, and that the last

two seem to have been rather neglected at that time (Kinjo, 1956b). Although

one can speculate about what this means, it is nevertheless a very interesting

piece of testimony by someone who was "there."

Ryusho Sakagami, in his 1978 Karatedo Kata Taikan as well as Tokumasa

Miyagi in his 1987 Karate no Rekishi both give extensive kata lists, and

both list a kata known as Yoshimura no Channan (Miyagi, 1987; Sakagami,

1978). It is unknown who Yoshimura was, but he may have been a student

of Itosu.

American karate historian Ernest Estrada has also stated that Juhatsu

Kyoda (1887-1968), a direct student of Kanryo Higashionna, Xianhui Wu

(Jpn. Go Kenki), Kentsu Yabu, etc. and the founder of the To'onryu karatedo

system, also knew and taught a series of two basic blocking, punching

and kicking exercises known as Channan (Estrada, 1998).

Shiraguma no Kata

According to Tsukuo Iwai, one of Japan's most noted Budo researchers

and teacher of Choki Motobu's karate in Gunma Prefecture, Motoburyu Karatejutsu,

which is being preserved by Choki's son, Chosei Motobu, in Osaka, contains

what is known as Shiraguma no Kata, which he maintains used to be called

Channan. He also states that this kata is "somewhat similar to the

Pinan, yet different." (Iwai, 1997).

The Other Side of the Coin

The flip side to this theory states that Itosu did not create the Pinan

kata, but actually remodeled older Chinese-based hsing/kata called Channan.

This theory states that Itosu learned a series of Chinese Quan-fa hsing

from a shipwrecked Chinese at Tomari, and reworked them into five smaller

components, re-naming them Pinan because the Chinese pronunciation "Chiang-Nan"

was too difficult (Bishop, 1999).

It has been argued that the source for these Channan kata was a Chinese

from an area called Annan, or a man named Annan (Bishop, 1999). On the

other hand, others say that the man's name was Channan (Iwai, 1992). Still

others go into even more detail, stating that Itosu learned these hsing/kata

from a man named Channan, and named them after their source, later adding

elements of the Kusanku Dai kata to create the Pinan (Gima, et al, 1986;

Kinjo. 1999).

There is also interesting oral testimony passed down in the Tomari-di

tradition that is propagated in the Okinawa Gojuryu Tomaridi Karatedo

Association of Iken Tokashiki that states that Itosu learned the Channan/Pinan

kata from a Chinese at Tomari in one day. The proponents of Tomari-di

said that there was no need to learn "over-night kata" and that

this is the reason that the Tomari traditions did not include instruction

in the Pinan kata (Okinawa Pref., 1995).

This sentiment also echoes the statement by one of Itosu's top students,

Yabu Kentsu, made to his students:

"(sic) If you have time to practice the Pinan, practice Kushanku

instead (Gima, et al, 1986, p. 86)."

Conclusion

While more research, such as in-depth technical analysis of Motobu's

Shiraguma no Kata, needs to be done, the evidence at hand seems to point

not to a "long lost kata" but rather to the constant and inevitable

evolution of a martial art.

Although there is opposition, most of the primary written materials point

to the fact that Itosu was indeed the originator of the Channan/Pinan

tradition, based upon his own research, experience, and analyses.

However, in either case, Anko Itosu and his efforts left a lasting mark

on the fighting traditions of old Okinawa, and will probably always be

remembered as one of the visionaries who were able to lift the veil of

secrecy that once enshrouded karatedo.

© 2000, by Joe Swift. Posted with

permission of the author.

Notes:

1- Japanese names in this article are listed by given name first and

family name second instead of customary Japanese usage which places the

family name first.

2- According to noted Japanese martial arts historian Ryozo Fujiwara

in his 1990 book entitled "Kakutogi no Rekish" (History of the

Martial Arts), Funakoshi first learned Pechurin (Suparinpei) under Taite

Kojo, then Kusanku under Anko Asato, and finally Naifuanchi under Itosu.

3- For a comprehensive English translation of this letter, see (McCarthy,

1990)

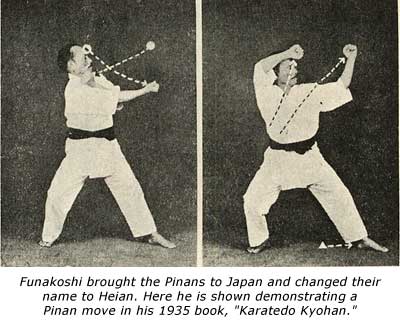

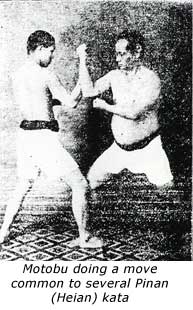

Photos:

The Itosu drawing was contributed by Kyoshi Frank Hargrove from his

book, The 100 Year History of Shorin-Ryu Karate. Since there are no know

photos of Itosu, the drawing was a composite done in Okinawa based on

available descriptions.

The Funakoshi photo was reproduced from his 1935 book, Karatedo Kyohan.

The Motobu photo was reproduced from his 1926 book, Okinawa Kempo: Karate

Jutsu on Kumite.

Bibliography:

Bishop, M. (1999) Okinawan Karate: Teachers, Styles and Secret Techniques,

2nd Edition. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle, Co.

Estrada, E. (1998). Personal Communication: Kyoda and Channan.

Fujiwara, R. (1990). Kakutogi no Rekishi (History of Martial Arts). Tokyo:

Baseball Magazine.

Funakoshi G. (1976) Karatedo: My Way of Life. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

Funakoshi G. (1988) Karatedo Nyumon. Tokyo: Kodansha International. Tr.

by John Teramoto.

Gima S. and Fujiwara R. (1986) Taidan: Kindai Karatedo no Rekishi wo

Kataru (Talks on the History of Modern Karatedo). Tokyo: Baseball Magazine.

Iwai T. (1992). Koden Ryukyu Karatejutsu (Old-Style Ryukyu Karatejutsu).

Tokyo: Airyudo.

Iwai T. (1997) Personal Communication: Shiraguma no Kata.

Kinjo A. (1999) Karate-den Shinroku (True Record of Karate's Transmission).

Naha: Okinawa Tosho Center.

Kinjo H. (1956a). "Pinan no Kenkyu (Study of Pinan) Part 1."

Gekkan Karatedo June 1956. Tokyo: Karate Jiho-sha.

Kinjo H. (1956b). "Pinan no Kenkyu (Study of Pinan) Part 2."

Gekkan Karatedo August 1956. Tokyo: Karate Jiho-sha.

Kinjo H. (1991) Yomigaeru Dento Karate 1 Kihon (Return to Traditional

Karate Vol. 1, Basic Techniques) - video presentation. Tokyo: Quest, Ltd.

Mabuni K. and Nakasone G. (1938) Karatedo Nyumon (Introduction to Karatedo).

Tokyo: Kobukan.

McCarthy, P. (1996) "Capsule History of Koryu Karate." Koryu

Journal Inaugural Issue. Australia, International Ryukyu Karate Research

Society.

McCarthy, P. (1999) Ancient Okinawan Martial Arts: Koryu Uchinadi, Vol.

2. Boston: Charles E. Tuttle, Co.

Miyagi T. (1987) Karate no Rekishi (The History of Karate). Naha: Hirugisha.

Motobu C. (1932) Watashi no Toudijutsu (My Karate). Tokyo: Toudi Fukyukai.

Murakami K. (1991). Karate no Kokoro to Waza (The Spirit and Technique

of Karate). Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu Oraisha.

Nagamine S. (1986) Okinawa no Karate Sumo Meijin Den (Tales of Okinawa's

Great Karate and Sumo Masters). Tokyo: Shin Jinbutsu Oraisha.

Nihon Karate Kenkyukai (1956) Zoku: Karatedo Nyumon (Introduction to

Karatedo: Continued). Tokyo: Wakaba Shobo.

Okinawa Prefecture Board of Education (1994). Karatedo Kobudo Kihon Chosa

Hokokusho (Report of Basic Research on Karatedo and Kobudo). Naha: Nansei.

Okinawa Prefecture Board of Education (1995). Karatedo Kobudo Kihon Chosa

Hokokusho II (Report of Basic Research on Karatedo and Kobudo Part II).

Naha: Nanasei.

Sakagami R. (1978) Karatedo Kata Taikan (Encyclopedia of Karatedo Kata.

Tokyo: Nichibosha.

Sells, J. (1995) Unante: Secrets of Karate. Hollywood: Hawley.

About The Author:

Joe Swift, native of New York State (USA) has lived in Japan since 1994.

He holds a dan-rank in Isshinryu Karatedo, and also currently acts as

assistant instructor (3rd dan) at the Mushinkan Shoreiryu Karate Kobudo

Dojo in Kanazawa, Japan. He is also a member of the International Ryukyu

Karate Research Society and the Okinawa Isshinryu Karate Kobudo Association.

He currently works as a translator/interpreter for the Ishikawa International

Cooperation Research Centre in Kanazawa. He is also a Contributing Editor

for FightingArts.com.

|