Enter The bubishi

Part 2- The Text & Its Impact On

Okinawa

By Victor Smith

Editor's Note:

This is the second article in a three part series

on the bubishi. Part

1 discussed the book's origin and introduction

through the writings of many early 20th century karate

masters. Part 3 will discuss the availability of translations

of the text in English, the text's impact on karate

today and the current status of research on this text.

The bubishi has over 30 chapters (depending on the

edition) that focus on a wide variety of topics, including

martial history, fighting strategy, vital point striking,

hand positions, essential fighting techniques, grappling

and escapes, herbal medicine treatment, forms and

techniques and martial code. It also offers some history

on the White Crane and the Monk Fist Kung Fu arts.

Patrick McCarthy in his translation of the text ("bubishi:

The Bible Of Karate") has organized the book's

information into four general categories, or parts.

He also includes an Introduction and historical perspective.

These parts include:

Part 1- Articles on history, concepts, strategy

and philosophy including White Crane and Monk Fist

Kung Fu.

Part 2- Articles, examples, definitions, diagrams

and recipes for Chinese medicine, specific remedies

and herbal pharmacology, including the concept of

12 hours chi (energy) flow (shichen cycle).

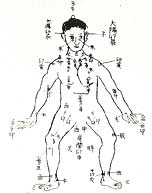

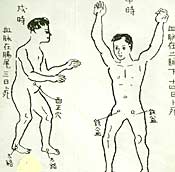

Part 3- Vital points including types, locations,

diagrams, periods for attack, restricted locations,

and delayed death touch.

Part 4- Fighting techniques, a list of kata moves,

eight principles, maims, principles, six open hand

positions, 48 self-defense diagrams, and Shoalin

hand and foot, muscle and bone training postures.

While many topics are discussed, most of the information

is presented in outline form and thus for most readers

will seem incomplete. For this reason many of the

topics can not be fully understood from the limited

information presented. For example, while the bubishi

offers many illustrations of vulnerable points, it

does not explain how to strike them, or what technique

to use. Thus many important details behind these practices

are missing.

This lack of detail lends some credence to the theory

that the bubishi may have been a personal notebook

rather than a textbook. If the author had been in

a martial training program, the notes taken would

have been cryptic, something designed to work as a

mnemonic device for future reference.

But the reader should not be discouraged, for there

are some fascinating chapters. For example, the bubishi

presents the principle of striking vital points according

to the Shichen theory of Traditional Chinese Medicine.

The theory states that body energy (chi in Chinese

or ki in Japanese) flows in natural cycles or tides

through the body and its organ systems, with each

24 hour cycle being divided into 12 two hour periods.

Based on this theory, certain points are more active

and more deadly during certain two hour periods. Thus

knowledge of where the Chi flow is during a particular

Shichen cycle allows the martial artist to locate

the most vulnerable points which could be struck.

Both the points and the optimum time for striking

them are illustrated. The text often suggests death

as the outcome, immediately or after differing periods

of time after being struck. (1)

|

In a different light, certain sections of the

bubishi could be seen as a medical text. The

charts showing where to strike vital points,

the charts showing the vulnerability of those

points during specific Shichen, as well as the

"correct" treatment for those injuries

might suggest the points are shown only for

medical treatment purposes.

|

|

|

|

Another section purportedly shows secret points

that can be struck that will have a killing

effect one-half or one year later. In some Chinese

arts this is known as the "Death Touch,"

or "Dim Mak."

|

The bubishi also contains considerable information

relating to fighting. It contains lyrical descriptions

of forms: some versions of the bubishi show a diagram

of techniques, possibly from a form (kata). There

are also discussions of combat principles and a lengthy

discussion on grappling and escapes.

|

Another interesting segment includes 48 Self

Defense Diagrams. In each case the outcome of

an encounter is shown. Both the winning and

losing technique are listed along with a short

synopsis of the strategy that led to victory.

Here again, however, there is minimal discussion

about how techniques can be applied.

|

|

Some authorities suggest that the practice of Okinawan

Karate may have been influenced by these 48 diagrams.

Many similar techniques can be found in many Okinawan

karate kata as well as part of self-defense exercise

sets. (2)

There are also chapters explaining herbal treatment

for illness and injuries. Except for anecdotal evidence

it is not known if these practices work or not. In

addition some translators have noted that mistakes

have crept into copies of the text, probably as a

result of people copying by hand information which

they are not familiar. (3)

I would suggest that these herbal formulas should

be carefully examined and not be experimented with,

except under the supervision of a trained expert in

Traditional Chinese Medicine knowledgeable in herbal

formulations.

The Impact Of The bubishi On Okinawa

We know the bubishi existed, but how do we track

the actual influence it had on the development of

the Okinawan arts?

We know that some important karate masters in the

past possessed copies of the bubishi, but there are

no published notes, direct studies, or even oral history

on the text's influence available for our review.

Also, exactly who and how many people possessed copies

of the text is open to which "legends" one

wishes to listen to.

Thus many questions arise:

Was the bubishi truly kept private for the select

few?

Were those who possessed the bubishi sufficiently

literate to read and understand the text which was

written in an older style Chinese dialect? And if

they could read the text, did they possess enough

knowledge of Traditional Chinese Medical theory to

use and apply the information?

Was the bubishi used to design training, such as

teaching the defensive theories directly to the students?

Or was the bubishi little more than a learned curiosity,

something valued but not understood, something to

be placed on the shelf to be revered but not actually

used?

Without historical proof, it is very difficult to

know the truth. We know that Mabuni, Funakoshi and

Yamaguchi felt the bubishi was important enough to

"announce" its existence by including portions

of the text in their own works. Others famous masters,

such as Higaonna, Itosu, Nakamura and others also

had the text and passed it on to their most trusted

students.

Miyagi Chojun also felt so strongly about the bubishi

that he reportedly took the term "Goju"

from it as the name for his system of training. According

to Patrick McCarthy (The Bible Of Karate: bubishi),

Miyagi took the name Goju from a section of the bubishi

titled, "The Eight Precepts of Quanfa" which

speaks of inhaling as representing softness ("Ju"

of Goju) and exhaling as characteristic of hardness

("Go" of Goju). (4)

Others suggest, however, that while Miyagi was influenced

by the bubishi, he took his style name from other

sources. (5) Material

in the bubishi may also have provided Miyagi with

inspiration for developing his famous Tensho (Rolling

Hands) kata.

Tatsuo Shimabuku (the founder of Isshinryu) chose

the eight poems of the fist (Chapter 13) of the bubishi

to be the Isshinryu Code of Karate.

But not everyone considers the bubishi to be influential.

Miyazato Eiichi, a long time student of Miyagi and

one of the principal inheritors of his system, believed

the bubishi was not important. He did not have a private

copy, however, and said that he had only seen it a

few times. (6)

As to the impact of the bubishi's sections pertaining

to chi meridian theory, there is no evidence that

they were used in the historical development of Okinawan

karate. Certainly there existed knowledge of vital

points and methods to strike them which relate to

acupuncture points. But, there is no evidence that

this knowledge was taken to a much more complicated

level which involved understanding not only concepts

of energy flow, but also related timing patterns.

From what I've heard, there is no evidence that the

Okinawans ever referred to the Meridian charts."

There have been many explanatory books and commentaries

written on the bubishi in Japan, none of which are

available in English. I also strongly suspect there

are many instructors who have prepared extensive analyses

concerning the bubishi, but this information is not

readily available to the martial arts community. A

great deal of time is likely being spent following

the same lines of thought over and over again due

to the unavailability of research and analysis of

the texts contents and theory.

Footnotes:

(1) Christopher Caile in a

communication with this author has noted that in addition

to the 24 hour cycle of Chi, what is also important

but unstated in the bubishi, is that chi theory (in

Traditonal Chinese Medicine) also includes a larger

yearly cycle that greatly influences the daily cycle.

Thus a technique based on the daily cycle will be

much more effective when done at a certain period

of the year. This, however, is not discussed within

the bubishi.

(2) Conversation with George

Donahue, a member of the Kishaba Juku organization,

related the following observation about the bubishi

to Christopher Caile: His organization has passed

down the work for five generations, having made hand

copies of the manuscript along with many notes. Donahue

believes, however, that the most useful information

is contained within the notes (overlays of onion skin

with notes) themselves. Included are critiques of

information within the bubishi including what works

and what doesn't. Thus, while the bubishi is considered

important in itself, it did not significantly influence

his organization or its teachings. One of the bubishi

copies, Donahu noted, was originally from Nakamura

sensei. Another one passed down is from the late Kishaba

sensei. Donahue's teacher and head of the organization,

Shinsato sensei, has collected, annotated and bound

a lot of information on the bubishi and other texts.

(3) Miyagi was well aware

of the bubishi and even quoted from the book in an

August 1942 essay that appeared in "Bunka Okinawa"

that was titled "Breathing In And Breathing Out

In Accordance With "Go" And "Ju":

A Miscellaneous Essay On Karate." Notice the

similarity of the essay's name with the section from

the bubishi after which Miyagi is reputed to have

named his style. It is perhaps this similarity that

led some to suggest that "Goju" as the name

for Miyagi's style came from this source.

(4) A more likely derivation

for Goju karate's name lies elsewhere. Representing

Miyagi at a 1930 All Japan Martial Arts Exhibition

was his senior student Jinan Shinzato who was asked

the name of his ryuha (school). Shinzato. The style

having no formal name at the time other than association

with its Nahate, Surite and Tomorite lineage, and

Shinzato replied to the question, "Goju"

(meaning hard/soft). This was later related to Miyagi,

who adopted the name. Others, however, suggest that

Shinzato never gave an answer to the question about

the name of his ryuha and that Miyagi later coined

the name after thinking the problem over.

(5) Information supplied by

Christopher Caile. In 1992 Caile had a private

translation made of the 39 pages from the bubishi

that appeared in Yamaguchi's book, "Karate-Goju-Rui

By The Cat." The translator, who is well versed

in Chinese herbal medicine, noted numerous inconsistencies

, possible errors, as well as the names of herbs not

generally recognized. It was suggested that these

unknown herbs might have been local herbs, or local

names for well-known herbs. Furthermore some methods

ofpreparation are not fully explained.

(6) From a private interview of Miyazato by Christopher

Caile held in Naha, Okinawa, while Mr. Caile was studying

in Miyazato's dojo in December, 1994.

About The Author:

Victor Smith is a respected teacher of Isshinryu

karate (6th degree black belt) and tai chi chuan

with over 26 years of training in Japanese, Korean

and Chinese martial arts. His training also includes

aikido, kobudo, tae kwon do, tang so do moo duk

kwan, goju ryu, uechi ryu, sutrisno shotokan, tjimande,

goshin jutsu, shorin ryu honda katsu, sil lum (northern

Shaolin), tai tong long (northern mantis), pai lum

(white dragon), and ying jow pai (eagle claw). Over

the last few years he has begun writing on, researching

and documenting his studies and experiences. He

is the founder of the martial arts website FunkyDragon.com/bushi

and is Associate Editor of FightingArts.com. Professionally

he is a business analyst, but also enjoys writing

ficton for the Destroyer Universe.

back

to top

home

| about

us | magazine

| learning

| connections

| estore

|