Martial Arts: Defining Martial Concepts

Okinawa's Bushi: Karate Gentlemen

By Charles C. Goodin

|

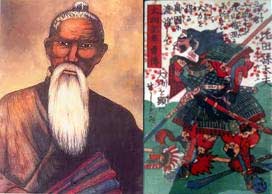

The Okinawan karate master Bushi Matsumura pictured next to a Japanese Bushi or Samurai. While the term "Bushi" was used in both the independent Kyukyu Kingdom (Okinawa and associated islands) as well as in feudal Japan, the meaning differed. (Images by FightingArts.com and Christopher Caile) |

Recently, I was conducting a search of Yoen Jiho Sha /1 issues when I came across an article entitled A Small Talk on Karate - Kinjo, a Benefactor of Karate-Do in Hawaii, by Sosen Toyohira. November 16, 1961. /2 One section of the article in particular caught my attention:

"In Okinawa, an expert of Karate was called a "Bushi," which meant a true gentleman or a noble character. In feudal times in Japan, in contrast, "Bushi" referred to "warriors" or "samurai." Karate is a defensive art only - it is never used for offense. It is a self-defense art that should be mastered to conquer oneself and learn to behave modestly. For that reason, a well trained Karateman was looked upon as a "Bushi" - a noble Karateman."

This discussion made me start thinking - how did the Okinawan and Japanese concepts of "Bushi" differ and what does this mean for students of Karate? I started to review literature and websites and quickly found that many people associate Karate "Bushi" with the Japanese concept of warrior or samurai. If Karate people are this type of "Bushi" it is natural to think that they should follow the Code of "Bushido", literally, the way of the "Bushi." While at it, why not throw in Zen training for good measure?

Now wait a moment - at the time of the formation of Karate, Okinawa was not part of Japan. The Ryukyu or Loo Choo Kingdom, of which Okinawa was the largest island, was independent (albeit dominated by its much larger neighbors). It traded with Japan, China and many other countries. It had its own king, political and social structure, language, religion, arts and culture (don't get me going on this). Okinawans were not Japanese. So why should their martial artists follow the Japanese Code of Bushido, which was only applicable to the Japanese warrior class?

Was the problem with the word "Bushi" itself? Fortunately, my sensei, Katsuhiko Shinzato, is a professor of linguistics at the Okinawa International University. /3 I emailed a series of questions to him about this subject.

He explained that although "Bushi" uses the same kanji and is pronounced the same in Okinawa and Japan, it means different things. In Japan, a "Bushi" was a member of the warrior class. In Okinawa, the term "Bushi" was honorific. It was used to refer to a Karate practitioner who was respected and revered not only for of his superior martial arts skill, but for being a civilized, principled gentleman as well. "Bushi" did not mean the Japanese "samurai." As evidence of this, even the Okinawan King's official guards, who were referred to as "samurai" in Okinawa, were not referred to as "Bushi."

As it turns out, different types of "Bushi" are recognized in Okinawa.

A "Kakure Bushi" is a "hidden Bushi", one who never tries to let himself be known as a Karate practitioner. Occasionally we hear about Karate hermits, experts who live in caves, tombs, or the mountains, and have completely withdrawn from society.

On the other extreme is a "Tijikun Bushi" or "knuckle or fist Bushi." This type of Karate practitioner has large, grotesque knuckles and is known for fighting skill only. He lacks the culture and principles of a gentleman. A reference to this type of "Bushi" can be found in Noma of Japan: An Autobiography of a Japanese Publisher, by Seiji Noma assisted by Shunkichi Akimoto, The Vanguard Press, 1934. Mr. Noma, a kendo expert, was stationed in Okinawa as a schoolteacher in 1904. Okinawa used to be referred to as Loo Choo (or Luchu) and Okinawans were called Luchuans. Tijikun is a Hogen (Okinawan dialect) term. Noma uses the Japanese term "teko" (knuckle):

"My unruly behaviour was not confined to drinking and courtesans. I fought with roughs and thrashed men for imagined insults. The Luchuans are a pacific people, but like all those given to strong drink and leading a primitive life, they would commit acts of nameless cruelty if their blood was stirred. The Luchuans had developed through centuries of practice the peculiar art of self-defence and aggression, known as tekobushi, which consists in making incredibly deft and powerful thrusts of the fist after the fashion of jujitsu or even boxing. This was the only possible mode of self-defence for the Luchuans, who had been prohibited the use of weapons by their double rulers of China and Japan. A Luchuan expert in the deadly art could smash every bone in his victim's body with the thrusts of his arms, as if he had struck with a giant hammer. Not infrequently poor victims were found dead by the road-side bearing marks of terrible blows from naked fists. Near Tsuji at night there were always gangs of roughs supposed to be skilled in tekobushi, who were ready to pick quarrels with unwary strangers."

A "Tijikun Bushi" is the worst type, since he is the most likely to harm others, and in the process, impugn the reputation of all other Karate practitioners. Morio Higaonna, /4 who visited me at the Hawaii Karate Museum in August, 2004, explained to me that such a person is also referred to as a "Bushi Gwa," or "small Bushi." "Gwa" is the Hogen word for "small." /5 A "Bushi Gwa" grasps only a small aspect of Karate.

Another negative example of a Karate practitioner is a "Kuchi Buchi," or "Mouth Bushi," one who pretends to be well trained by bluffing. While a "Tijikun Bushi" might have callused, wart-like knuckles, a "Kuchi Bushi" has a silvery tongue - he can talk the talk but not walk the walk. He lacks or only has a low level of martial skill. Such a person spends more time reading about Karate than training and tends to dwell on and exaggerate the exploits of famous fighters. In doing so, he misleads young students who are easily impressed and distracted.

Higaonna Sensei also mentioned that there is an "Uhu Bushi" or "Greatest Bushi." He recalled hearing Kanryo Higaonna (an outstanding proponent of Naha-Te) referred to as "Uhu Bushi Higaonna No Tanme." "Tanme" is Hogen for "respected elder."

Shinzato Sensei further explained that "Uhu Bushi" is an honorific term for one who was the greatest among certain schools or styles of Karate. Kanryo Higaonna was considered to be the originator of present Goju-Ryu and thus deserved the title "Uhu Bushi." Likewise, in the genealogy of Shorin-Ryu, Sokon Matsumura and Kosaku Matsumora would be referred to as "Uhu Bushi" as they are regarded as the restorers of Shuri-Te and Tomari-Te respectively.

Now before anyone runs off to change their email address to "Bushi" or "Uhu Bushi," these terms are honorific: titles or phrases conveying respect. They are only used by others. I'm sure that Sokon Matsumura never introduced himself as "Bushi," nor has any sensei I have ever trained with referred to himself as "Sensei." Perhaps the only person who would do so is a "Kuchi Bushi" or "Bushi Gwa."

These terms also seem to be more or less reserved for the leading Karate experts of the 19th century or earlier. Anko Itosu was certainly a "Bushi" by any standard, but I have never heard him referred to as such. The same applies to Kentsu Yabu, Chomo Hanashiro, Chotoku Kyan, Chojun Miyagi, Choshin Chibana, and others noted Karate practitioners.

The case of Sokon Matsumura deserves special attention because it both highlights some of the confusion surrounding the term "Bushi" and provides an example of what a "Bushi" truly is. Born in Shuri in 1809, Matsumura practiced the fighting traditions of both Okinawa and China, and also studied Jigen-ryu Kenjutsu (swordsmanship) while in Kagoshima (Satsuma). Due to his prowess in both Karate (which then was referred to as "China Hand") and intellectual studies, such as calligraphy, he ultimately served three Kings. There can be no doubt that Matsumura was an outstanding martial artist, one of the finest ever. However, he was not called "Bushi" simply because of his martial skills, nor was the title given in recognition of the fact that he was a "samurai" (or bodyguard) for kings, or trained in swordsmanship in mainland Japan.

Instead, Matsumura was given the title of "Bushi" by retired King Shoko-O (then called Boji-Ushu) for something he did not have to do. By now, I'm sure that you know I am referring to the episode of Matsumura defeating a wild bull. This story has been told in many books, but in a nutshell, Boji-Ushu asked Matsumura to fight a bull that had become a nuisance. In those days in Okinawa, bullfights were staged between two bulls. Knowing of Matsumura's Karate skills, the King wondered how Matsumura would fare.

When the time came for the fight, Matsumura entered the arena. He was either wearing a certain colored robe or carrying a small wooden club (depending on who tells the story). Upon seeing Matsumura, the bull cowered and ran away. It was terrified.

Before the stunned crowd, the ex-King promptly pronounced that Matsumura was to be known thereafter as "Bushi Matsumura. As we all know, Matsumura had sneaked into the bull's pen at night for the week preceding the match and beat it fiercely on the nose with a club. No wonder it was terrified when it saw him! What we don't know is whether the ex-King ever found out about Matsumura's strategy.

Now, if Matsumura had been a Tijikun Bushi, he might have killed the bull or it might have killed him. Perhaps he might have succeeded in breaking of its horns. But at best he would have been considered to be a "Bushi Gwa". Had Matsumura been a "Kuchi Bushi," he could have lectured the bull, boasted about his exploits, or shouted at it, but the outcome would have been certain - he would have been gored and probably killed. But because Matsumura was a true "Bushi," an "Uhu Bushi" at that, both he and the bull lived to see another day.

In a letter to his student Ryosei Kuwae, Matsumura described three forms of martial arts: gakushi no bugei, meimoku no bugei, and budo no bugei. The first two categories roughly equate to "Kuchi Bushi" (mouth Bushi) and "Tijikun Bushi" (fist Bushi). Only the third category is worthy of study. As he writes:

"[B]udo no bugei, [are] the genuine methods which are never practiced without a conviction, and through which participants cultivate a serene wisdom which knows not contention or vice. With virtue, participants foster loyalty among family, friends and country, and a natural decorum encourages a dauntless character. With the fierceness of a tiger and the swiftness of a bird, an indomitable calmness makes subjugating any adversary effortless. Yet budo no bugei forbids willful violence, governs the warrior, fortifies people, fosters virtue, appeases the community, and brings about a general sense of harmony and prosperity. These are the "Seven Virtues of Bu."

Tales of Okinawa's Great Masters by Shoshin Nagamine. Translated by Patrick McCarthy. Tuttle Publishing, 2000. Page 21. Matsumura adds that these seven virtues were praised in the Godan-sho, an ancient journal about China.

As we can see, Matsumura did not (at least not in this letter) praise Bushido or Japanese martial values. He did not talk about service to one's lord or selfless sacrifice, about honor or duty. Instead, the goal is to "cultivate a serene wisdom which knows not contention or vice."

Matsumura did not kill the bull, nor did it kill him. By beating the bull on the nose, he saved both of their lives. This is what made him a "Bushi."

When were the values of Karate replaced by Japanese values? When did the Okinawan "Bushi" become modern day samurai?

It is natural that Karate underwent major changes when it was assimilated into the Japanese nation and culture. First, Karate had to be changed in Okinawa once the Kingdom was abolished, the King was forced into exile in Tokyo, and the former lands became a Japanese prefecture. In order for Karate to be practiced in the Okinawan school system (introduced principally by Anko Itosu and Kanryo Higaonna), it had to satisfy the Japanese administrators and head teachers, most of whom, at least initially, were sent from Tokyo. Techniques were camouflaged or completely eliminated, at least in the public classes. Physical training became geared toward preparing young men for military service. Students were taught to be good Japanese subjects, to acquire the Yamato spirit (Yamato damashii).

When Gichin Funakoshi, an Okinawan schoolteacher, and his contemporaries such as Choki Motobu, Kenwa Mabuni and Chojun Miyagi, took their native Karate to the Japanese mainland about 15 to 20 years later, the recently modified art underwent even further changes. Japanese students were already raised to value the ways of the Japanese "Bushi" or samurai, who were held up as prime examples of character. Japanese students did not learn Karate as a way to better understand Okinawan culture and values. Why should they? Okinawa at that time was generally looked down upon as a backward and poverty stricken prefecture populated by peasants and farmers. Why do you think so many early writers stated that Karate was developed by Okinawan farmers rather than acknowledging the central role of members of the noble and gentry classes?

Japan had a highly developed culture and its own proud martial arts tradition. In order for Karate - a foreign art -- to be accepted at that particular point in history, it had to conform to Japanese budo traditions and philosophies. The techniques of Karate were absorbed, and then modified (some say perfected), and the Okinawan values, which were derived largely from China, were replaced by discipline, obedience and service to country and emperor. The philosophy, or character orientation, of Karate became indistinguishable from Judo or Kendo.

All Chinese vestiges of Karate were stripped out. Kata names, many of which were the actual names of the Chinese experts who taught or originated the kata, were changed to Japanese terms. Movements became more rigid and militaristic. In a remarkably short time, Tote Jutsu (China Hand Art) became the generic Karate Do (the Way of the Empty Hand). /6

Part of this was undoubtedly due to the turbulent times during which Karate entered the Japanese mainland. While Anko Itosu described Karate "as a means of avoiding the use of one's hands and feet in the event of a potentially dangerous encounter with a ruffian or a villain" (Tales of Okinawa's Great Masters, page 56), Japanese university students were being prepared for ongoing military conflicts with China and ultimately for the looming war in the Pacific. Karate had to be taught quickly - intensely, but quickly. After a few short years of college, most students were off to war. But those wars are long over.

Karate also underwent a form of "metric standardization" in which the approach shifted from the qualitative to the quantitative. A 10 level system of kyu and dan ranking was adopted. The Dai Nippon Butokukai (the official governing body for martial arts in Japan) began to award Renshi, Kyoshi and Hanshi titles to Karate experts. Karate, an art which had been directed toward the cultivation of the character, became characterized by externalities. What is one's rank? What is one's title? How many kata does one know? How many tournament victories does one have? How could students be faulted for seeking such forms of recognition when the basic structure of the art was changed to encourage it?

There is another, perhaps even more important reason for the change in Karate values - the shift from teaching only a few, private students to teaching large classes. Whether Karate is taught in Okinawa, Japan, England, Hawaii, or any other location, there is a fundamental difference between one-on-one and group teaching. How one teaches a few students differs from how one must teach 50, 500, 5,000 or 50,000 students. It is one thing to personally counsel a student about critical issues in his life. It is quite another to make him memorize and recite dojo kun (a list of precepts). Teaching and instilling character requires a personal touch.

Teaching Karate to a large number of students also introduced issues of group dynamics. Instead of learning from a single sensei, perhaps for life, new students entered classes or dojo that were part of larger organizations or associations. Fiscal, administrative and political skill became important parts of the game, particularly when Karate evolved into a business and some instructors became "professionals". Rather than turning the student's attention inward to the cultivation of his character, modernized Karate increasingly required him to become a businessman. And the negativity of politics has definitely caused some of the most sincere Karate instructors and students to leave the art in disgust.

Of course, these changes did not only take place outside of Okinawa. To a large extent, "innovations" introduced in Japan and later the West, particularly structural ones, were eventually copied in Okinawa. Karate is not traditional simply because it is practiced in Okinawa (or Japan) - it is only traditional when it is squarely based on traditional values.

I will never forget a telephone conversation I had several years ago with Walter Dailey, who then was the publisher of Bugeisha: Traditional Martial Artist. Daily had studied Shorin-Ryu in Okinawa under Zenryo Shimabukuro, who had studied under Chotoku Kyan (Chan Migwa), who in turn had studied under Bushi Matsumura, among others. During the course of our conversation, Dailey said that "Karate makes us into gentlemen." He emphasized the word "gentlemen" and it stuck in my mind.

Recently, I called Dailey Sensei to discuss this issue again. It was as if I had hit a bull's eye. Daily almost shouted, "that's it!" "That is what is missing in Karate today." He explained that he learned more about being a gentleman by observing his sensei before and after class -- how he carried himself, how he reacted with others, how they reacted to him - than he did in actual class. "Character is the goal. Karate training is simply an excuse for developing character. Blood, sweat and tears are to form the character of the student. Karate is a means to an end."

Character is not one of the benefits of Karate training. It is the goal. Without it, there is no Karate, only athletics.

Students come to a sensei with many problems: some are timid, some are angry, some are weak, others are egotistical. Whatever their problems may be, the sensei works to help the students to overcome them and develop a good character. To allow a student to develop fighting skills without a good character is unforgivable. To say that "modern Karate" does not need to require character training, is equally wrong. To be blunt, students with bad characters must either improve or quit because the sensei is responsible for their actions.

I thought a great deal about Dailey Sensei's words. I cannot emphasize how important the issue of character was to him, and was to his sensei. It is equally important to many karate seniors I have met over the years. Unfortunately, it is not something you hear much about. When is the last time you went to a Karate seminar and saw "Character" listed among the session choices?

Three new students recently joined my dojo. Each time I receive a new student, I feel a greater sense of responsibility. My job seems more overwhelming. I feel like telling a new student that Karate training, for him, will be like climbing a mountain. Teaching Karate, for me, will be like taking a pick and shovel and moving that mountain!

In a way, the sensei is a painter. The student is the canvas and Karate is the paint. The subject of the artwork is character.

As the student progresses, he starts to paint as well. At first, his subject is his sensei. Gradually, he sees beyond that and realizes that his own character and actions in daily life are the subject and his sensei and other seniors are just examples (hopefully good ones).

One day, the student becomes the painter for a new generation of students. But character is always the subject and Karate is simply the paint, or an excuse for making students into gentlemen, and in very rare cases, for making Karate practitioners into "Bushi."

Mitsugu Sakihara was a professor of Okinawan Studies at the University of Hawaii. Several years ago, when he learned about my Karate research, he took me to lunch. His message was simple: "if you are going to study Karate you must also study the Okinawan culture." He died not too long ago, but I remain guided by his words, which have been repeated to me often by Okinawan seniors.

Karate has spread to the entire world. People of all races, cultures and religions practice and teach it. It is perfectly natural that Sensei will be guided by their own life experiences in striving to make their teaching meaningful and relevant to their students.

When we study Karate, wherever we may reside, we should always remember to study the culture and values that produced it. In doing so, we can learn much from the lives of Okinawa's "Bushi" -- Karate practitioners who were respected and revered not just for of their superior martial arts skill, but for being civilized, principled gentlemen.

I would like to thank Professor Katsuhiko Shinzato, Sensei Morio Higaonna, and Sensei Walter Dailey, for their invaluable input and guidance concerning this article.

About The Author:

Charles C. Goodin is an instructor of Kishaba Juku Shorin-Ryu Karate and Yamani-Ryu Bojutsu at the Hikari Dojo in Hawaii. He is a well known historian and prolific writer on Karate in Hawaii and its history and was responsible for the reestablishment of the Hawaii Karate Seinenkai and the formation of the Hawaii Karate Museum and its rare karate book collection. He is also a member of the Hawaii Karate Kenkyukai. Goodin is a Contributing Editor to the “Classical Martial Arts Magazine,” formally known as the Dragon Times, as well as being the former editor of “Furyu: The Budo Journal.” In his private life Goodin in an attorney. Several of his articles appear on FightingArts.com. |