Martial Arts: History and Historical Figures

Ghosts of the Samurai - A Visit to Matsue

By Deborah Klens-Bigman

Japan is a 21st century country, and yet, one does not have to go far to find the ghosts of another Japan—an old graveyard behind a wooden temple, a Shinto shrine surrounded by dark greenery set back from a noisy street.

|

Map of Shimane prefecture, showing Matsue, right, and Izumo, left, with Lake Shinji in the center (Google Maps). |

The men at once hastened to the cemetery; and there, by the help of their lanterns, they discovered Hoichi—sitting alone in the rain before the memorial tomb of Antoku Tenno, making his [lute] resound, and loudly chanting the chant of the battle of Dan-no-ura (Hearn 1971, 14).

Japan is a 21st century country, with high-speed rail that allows businesspeople to travel from Tokyo to Osaka for meetings and back the same day, and GPS that allows delivery trucks to prowl the winding streets of even the smallest village with confidence. And yet, one does not have to go far to find the ghosts of another Japan—an old graveyard behind a wooden temple, a Shinto shrine surrounded by dark greenery set back from a noisy street.

The writer of the above quote, Lafcadio Hearn (1950-1904), was a British expatriate who became one of the first popular interpreters of Japanese traditional culture in the West. Born in Greece and raised in Ireland, Hearn came to the US as a young man. He was a semi-successful writer in the US who nevertheless did not seem to fit in with the ways of the West, let alone American life. At times an ethnographer, at others a muckraking journalist, Hearn never seemed to find an authorial voice or even a congenial field in which to hone his talent. At the age of 40, out of what was almost desperation, he took a post teaching English in Japan. Hearn instantly fell in love with the place and its people, and there found himself a home, marrying and raising a family. He was subsequently adopted by his wife's family and became a Japanese citizen, taking the name Koizumi Yakumo.

Hearn's first posting was to Yokohama, where there was just enough of a hint of "old Japan" in the rapidly modernizing port city to awaken in Hearn an intense interest in traditional Japanese culture and whet his taste for Buddhism, about which he had done some extensive reading. Shortly after his arrival in Japan, however, he took another job in the small town of Matsue.

In Matsue, apparently Hearn found the shadow of the Japanese feudal past that he was seeking. According to biographer Jonathan Cott, Matsue, located south and west of Tokyo, was small and out of the way enough for Hearn to escape the mad pursuit of all things modern and Western that gripped late 19th century Japan. That Matsue was also held by the Matsudaira clan, relatives of the Tokugawa shoguns, probably accounted for a certain amount of historical stubbornness as well. Matsue had done well under the feudal system, and though there was no outright rebellion like there was in other parts of the country, people maintained much of their older way of life (Cott 1991, 263). Hearn instantly set about learning as much about the history and ways of the area as possible. Many Japanese feel even now that Hearn's work, writing down observations and recording everyday small town life, as well as preserving folktales, helped keep alive a sense of the past which might otherwise have gone missing in the rapidly industrializing country (Fackler 2007, 2). More than 100 years after Hearn's death, in the fall of 2007, I went to find out just how much Matsue still remembers of its samurai past.

I admit to more than simply historical interest. As some who know me are well aware, I love hot springs. My trip to Matsue was timed specifically to come after a week of official obligations, and though I could not shake them all, I deliberately booked myself into a hot spring hotel, determined to get the most out of the visit for both body and soul. The hotel, the Ichibata, included onsen (hot spring) facilities and a spectacular "Sky Bar" with a view of mirror-smooth Lake Shinji, which happened to be just down the hall from my room, but more about that later.

Hearn settled into Matsue in 1890. The first winter on his own was brutally cold, causing Hearn to become quite ill. A colleague, worried about his health, came up with an old-fashioned solution. He introduced Hearn to a young woman of an impoverished former samurai family, whom he eventually married (Cott 1991, 283). Hearn stayed in Matsue for only a total of 15 months, until financial obligations forced him elsewhere, but his life was transformed. Matsue remained a strong influence on Hearn as an echo of a Japan he regretted never being able to see before the onslaught of railways, steamships and kerosene oil (Hearn 1971, 211). He may the best guide I can think of for someone like myself, who is also constantly looking for hints of the past in the bustling Japanese present.

Hearn wrote wonderful descriptions of his surroundings in Matsue, and some of them hold true today. While I was not able to visit all of the places Hearn wrote about, I did get to a few during my brief visit.

|

Matsue jo. |

Crested at its summit, like a feudal helmet, with two colossal fishes of bronze lifting their curved bodies skyward from either angle of the roof, and bristling with horned gables and gargoyled eaves and tilted puzzles of tiled roofing at every story, the creation is a veritable architectural dragon, made up of magnificent monstrosities…(in Cott 1991, 278)

Matsue Jo stands imposingly on a slope rising up from the lake shore, and though the surrounding buildings have become much larger than in Hearn's time (not to mention now sporting more colorful, neon signs) it is still visible from many parts of town. Matsue jo was completed in 1611 by a local daimyo, Horio Yoshiharu. Eventually, the fief was taken over by members of the Matsudaira clan, in 1638. They ruled the area until the end of the Tokugawa era, in 1868 (Matsue Jozan Koen Administrative Office n.d., 2-3).

|

A close up shows the ishiotoshi (openings through which stones could be dropped on adversaries). |

Like several other old castles I have visited, Matsue jo was never burned down by lightning or in battle. Being a wooden structure, however, it has been extensively rebuilt over time. For lack of a better place, some of the old, worn elements are on display as visitors enter through the imposing iron doors.

|

However, if one looks closely, it is not difficult to discern some wooden pieces, if not original, as being very old and still in use. |

|

Iron doors protect the entrance to Matsue jo. |

|

An old beam in Matsue jo. |

Matsue jo is made up of beams coming out from the center, similar to the castle in Matsumoto, rather than utilizing a single, massive, central beam like that in Himeji castle.

|

Interior beam construction. |

Like nearly all intact battle castles and large turrets, the number of openings to the outside are deceptive - there are more floors inside than can be readily perceived from without. The stairways, though rebuilt with handrails, are probably as steep as the originals, and the view of the surrounding town from the top once again speaks to castle designers' obvious interest in strategic layout.

Like Matsumoto jo, Matsue jo was not the daimyo's residence, but rather a workplace. The daimyo's palace (being a member of the Matsudaira clan, it most likely was a palace) long ago disappeared, though one can see the foundation outlined by stones nearby. Except for a substantially large kitchen, the castle itself is austere and imposing, evoking a feeling still similar to Hearn's that it is still, after many centuries, somewhat forbidding.

The outer perimeter walls are of some interest in that the stones, raised by subscription by subordinate clans, are fitted together rather than chiseled into shape.

|

Fitted, rather than worked, stones make up the walls. |

On some, the names of the obligatory donors can still be seen.

|

A donor’s mark can be seen on one of the wall stones. |

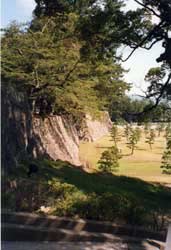

Though parts of the inner moat still exist, the massive outer walls flank a public park instead of a wide channel of water.

|

The inner moat still exists ... |

|

… while the outer one has been filled in. |

Still seeking the ghosts that Hearn had written about so extensively, I visited the ruined temple of Gesshoji. Built in 1644, Gesshoji was once the imposing family temple of the Matsudaira clan. The building was dismantled in the later 19th century, apparently because the new Meiji government had no interest in keeping such a powerful symbol of the feudal era intact. What remains are a series of imposing gates reflective of different periods of Japanese temple architecture, and beyond the gates, massive sets of grave stones of members of the Matsudaira clan.

|

One of the famous gates of Gesshoji, with a grave monument visible in the background. |

Even though it was broad daylight on a warm day in September, there was something definitely chilling and creepy about these groupings of huge, carved stones, surrounded by dense, dark green foliage.

|

Dark trees surround the grave markers at Gesshoji. |

In a small way, I perhaps felt something of the ghostly presence of the powerful clan. I have not read all of Hearn's writings, but they included a lot of ghost stories. After Gesshoji, I felt as though I could write one or two myself!

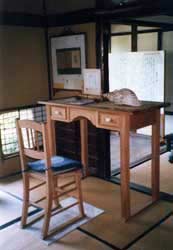

From Gesshoji, I took a cab (it was a long walk, and unfortunately I did not have much time) down the slope to the Lafcadio Hearn Museum. Various artifacts from Hearn's life were on display. His original writing desk, custom-built with very long legs to accommodate Hearn's one good eye, was just inside the entry way. His pipe collection and some original manuscripts and first editions were also on display, but the best part of the complex, the part that made Hearn's ghost most clear to me, was his house.

The house was not the original, small building where Hearn spent that first miserable winter by himself. Instead, it was a yashiki, a samurai dwelling, to which Hearn and his new wife moved once some Stateside royalty checks allowed him to afford more comfortable surroundings (Cott 1991, 295). Still, by Western standards, it is quite small, but exquisite, made over to accommodate the eccentric taste of its owner, a blend of Western necessity with very traditional Japanese style.

|

|

Traditional furnishings in Lafcadio Hearn’s house. |

A replica of Hearn’s desk stands in for the original, now in the Lafcadio Hearn Museum building. |

A replica of Hearn's tall desk sat where he once used to write, and on three sides shoji slid open to reveal a wonderful garden, still filled with late summer flowers.

|

|

A view of Hearn’s beloved garden. |

Another view of the garden at Hearn’s yashiki. |

Hearn was very fond of his garden. He wrote "There are no sounds but the noise of birds, the trilling of semi [cicadae], or, at long, lazy intervals, the solitary plash of a diving frog" (in Cott 1991, 296). Fatigued by the rigors of his teaching job or needing to take a break from his writing desk, Hearn lovingly described sitting on the veranda admiring the garden - flowers, trees, frogs, fish and even a pet snake! (Cott 1991, 296) Nowadays the garden is tended to by volunteers, and even though Hearn writes of having a gardener, the current caretaker said the garden is more beautiful now than it was in Hearn's day (I did not, however, see any snakes).

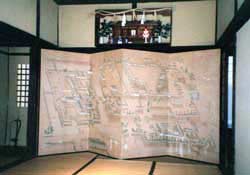

Not far from Hearn's house another traditional yashiki was open to public view. Though it featured a number of Edo period artifacts, including byobu (folding screens), kitchen furnishings and the like, the setup was much more museumlike and not nearly as charming or inviting as Hearn's. If one has not seen much of Edo period furnishings, it's worth a visit; but I found it overall rather dull, driven by a sense of "it's old, let's display it" rather than any kind of sensibility of a previous owner.

|

An old screen depicts a castle town (possibly Matsue) in the Buke Yashiki (“Old Samurai House”). |

It was now mid-afternoon, and I very much wanted to go to Izumo Taisha (Izumo Grand Shrine) before dinner. Izumo Taisha is reputedly the oldest Shinto shrine in Japan, steeped in tradition. The hotel clerk outlined instructions. Izumo was about 1/2 hour away by train. Though Hearn left Matsue for Kumamoto and later lived in Tokyo, he often harkened back to his time in Matsue as sort of a golden period of his life, and it was easy to see why. The short ride was spectacularly scenic, with Lake Shinji shimmering in the late afternoon sun.

Izumo, in spite of its significance, is a small town, and it was very simple to find my way to the shrine entrance. It was also very hard to miss - a massive walkway flanked by ancient trees bending in on either side, going on for nearly a mile to the shrine complex itself.

|

Old trees line the walkway to Izumo Grand Shrine. |

A very old shrine like Izumo and those at Ise are very different from the openness of more modern complexes like the Meiji Shrine in Tokyo. Broad gravel lanes lead to Meiji Jingu ("jingu" being a designation for a lesser shrine than "taisha"), but after the tree-lined entrance to Izumo Taisha, the complex itself is designed to increase the sense of mystery. Believer or not, it is very difficult not to feel a sort of spiritual power emanating from the place, as though centuries of human devotion had somehow rubbed off on it.

|

The outer pavilion at Izumo Grand Shrine. |

The visitor's pavilion is the most open area, which includes a large space for the performance of sacred dances.

|

A gigantic rice straw rope hangs in the pavllion. |

There is a legend that Okuni, the legendary founder of kabuki, was a dancer from Izumo, who turned her talents and business savvy into a thriving performance genre in (then) faraway Kyoto.

The most sacred of the shrine buildings are partially concealed behind old wooden fences. By walking around and peering inside at various places, visitors can see the inner sanctum; however, it is impossible to see it as a whole all at once. Only the roofs of the buildings are visible from the outside.

|

The inner sanctum at the Izumo Grand Shrine, barely visible. |

Even though it was getting late, the shrine precinct was full of visitors. Priests played music for a service being performed on behalf of some worshippers.

|

Shrine priests play music for a private ceremony at the Izumo Grand Shrine. |

A busload or two of tourists were milling about, snapping photos and buying omomori (charms for good health and longevity) even as the miko (shrine priestesses) were trying to close up shop.

It was time for me to go also. Ryokan (traditional inns) like the one where I was staying expect guests to be on time for dinner, and I had just enough time to make it. It's worth the minor inconvenience - the inns have no set menus but make their own daily specialties that take into consideration the season as well as famous dishes from the region. This place, like others I have visited, did not disappoint in the slightest.

After that, it was time for a dip in the onsen. Modern Japanese onsen have developed spa sensibilities. In addition to a hot mineral water soak, they now include whirlpools and other services, like massages and facials. I contented myself with a mixed approach - a spell in a very hot, dry sauna (95 degrees centigrade!) and a soak in a mineral pool that was open to the night sky. Afterwards it was off to the Sky Bar for a nightcap overlooking the lights reflecting on the calm surface of Lake Shinji. Hearn wrote admiringly of the lake, though I am certain he never got to see it from eight stories up. All the same, it seems that for all the bustle of a modern city, Matsue strives to maintain a sense of calm that I hope Hearn would still recognize and appreciate.

A new light rises in the east; the moon is wheeling up from behind the peaks, very large and weird and wan…wayfarers are paying obeisance to O-Tsuki-San; from the long bridge they are saluting…the White Moon-Lady (Cott 1991, 282).

About The Author:

Deborah Klens-Bigman is a NYC teacher of iaido.. She has also studied, to varying extents, kendo, jodo (short staff), kyudo (archery) and naginata (halberd). She received her Ph.D in 1995 from New York University's Department of Performance Studies where she wrote her dissertation on Japanese classical dance (Nihon Buyo). and she continues to study Nihon Buyo with Fujima Nishiki at the Ichifuji-kai Dance Association. Her article on the application of performance theory to Japanese martial arts. She is a frequent contributor to FightingArts.com. |