The Old Okinawan Karate Toe Kick:

Part 2- Historical Introduction

By Christopher Caile

Editor’s Note: Part

1 of

this series introduced the subject of toe kicks and provided the

basics

of how they are performed. Part 2 provides a historical introduction.

Also discussed is the author’s own introduction to toe kicks,

as well as some of the early great Shorin ryu masters who used

this kick. Targets and strategy of application are also addressed.

Future

articles will continue the discussion of toe kicks through the

Naha lineage, and also trace their use through several other Shorin-ryu

masters. Conditioning and development of the toes will also be

discussed

in a separate article. |

|

Introduction

Most of today’s Japan karate stylists (as well as Korean style

martial artists) and tournament oriented karate-ka probably have never

seen a toe kick. They would be surprised to learn that toe kicks were

once part of the “meat and potatoes” of old style self defense

oriented karate—dangerous and deadly.

Toes can become powerful, precise weapons, able to strike with needle

nose accuracy and penetrate—causing pain, neurological incapacitation,

and internal damage to organs, nerves, veins and arteries. The delayed

effects can manifest themselves days, weeks, months or even years later

(known as DIM MAK).

They were once principal techniques within the two great Okinawan historical

traditions from which modern karate evolved – Naha-te and Shuri-te

(better known as Shorin-ryu karate).

Naha-te (Naha referring to the town of Naha and “te”or “ti” meaning “hand,” a

term used to refer to fighting arts) includes such styles as Goju-ryu,

and Uechi Ryu (major styles), as well as To’on ryu and Ryuei-ryu

(minor styles). The term also has a secondary meaning of “new things,” (1) as these arts developed around a port city known for immigrants, visitors,

and new types of imported products. Thus, the term “Naha-te” reflects

a new or younger karate, one more directly connected to Chinese roots

with less influence from indigenous arts.

Shuri-te means “Shuri hand”(after the capital town of Shuri,

the political center of the island and residence of the King and other

gentry), a name that suggests older or more developed karate. Today the

term Shuri-te, however, is better known as Shorin-ryu (Okinawan for Shaolin,

the famous Chinese center for martial arts) -- a mixture of Chinese arts, “ti” (indigenous

fighting techniques) and other influences.

There was a third Okinawan karate tradition as well, Tomari-te. It has

largely disappeared, although much of it has been absorbed by Shuri-te.

It is not discussed separately here.

Historically it was Shorin-ryu teachers who are best known for first

establishing karate on mainland Japan, although there were Goju teachers

as well. From these teachers sprang such styles as Shotokan, Wado-ryu,

Shita-ryu, Chito-ryu, Goju-ryu, To’on ryu (now headquartered in

Japan), Kyokushin, as well as many European and US based traditional

Japanese karate organizations, such as Seido Juku. Japanese Shorin-ryu

stylists also helped establish Korean karate (Taekwondo and Tang Soo

Do, etc.) in the late 1940s and early 1950s, and their kata also closely

followed the Shorin-ryu template.

Thus, if you are a Japanese karate-ka or Korean stylist, or an offshoot

of one, you can probably trace your roots and your technique to Shorin-ryu

or Naha-te styles whose masters used toe kicks. And if your style is

Shorin-ryu related, your kata once used toe kicks too -- Heian (or Pinan,

the original Okinawan name), Kanku (or kusanku), Hangetsu (or Seisan),

Gangaku (or Chinto), Enpi (or Wansu), Bassai (or Passai), Gojushiho (or

Useshi also known in some styles as Koryu-gojushiho) and others. (2)

Even if your style no longer practices this kick, it still has relevancy

for you. If you are interested in street self-defense applications, the

tip of a boot or leather shoe can be used as a powerful, pin-point and

effective weapon.

My Introduction

When I started Kempo Karate we didn’t use toe kicks. Later, I

traveled to Japan and in 1961 become a student of Mas Oyama (Kyokushin

karate) in Tokyo, but again, toe kicks were not practiced. (3)

It wasn’t until the mid 1980s that I was introduced. I was living

in Buffalo and teaching Seido Juku Karate. I had decided to research

the roots of my own system and was looking to expand my knowledge. Through

a friend at the University where I taught karate, I started training

in a closed Chinese family kung fu system in Toronto. (4) It used pointed

toe and other unique kicks (wearing soft sandals) that I had not seen

before.

One hot summer evening when I first started, I was practicing this art

in an unventilated basement under a Chinese restaurant in Toronto. Our

tee shirts and shorts were soaked with sweat. Toward the end of practice

the Sifu (a term used for teacher in many Chinese arts) separated the

students into pairs to work on their own. My partner was his nephew Lee,

and we started self-defense drills. He said, “Step and punch at

my head –Hard!” I did and “POW” – I don’t

know what happened, but as a stunned and now very humble student, I looked

up at him from the floor. Lee was laughing. “Works doesn’t

it?” he said. I had no idea what he was talking about – I

hadn’t seen the toe kick to the inside of my knee, but it had made

its point.

When we repeated the technique, Lee showed me what he had done. He had

countered me with a double arm and kick combination. In one movement

Lee had brought one arm up inside my punch to block while the other arm

moved straight toward my head, with open hand to my eyes (which is why

I hadn’t seen the kick -- in a real self-defense situation the

fingers would have made contact). At the same time Lee had brought up

a short, snapping toe kick to the inside of my upper lead leg – which

totally collapsed. I was stunned too. After this, Lee was careful only

to tap with his kicks on selected places.

A few years later I also took up Praying Mantis Kung Fu, which also

utilizes some specific types of toe kicks. Later in the mid-1990s when

I visited Okinawa, I made a point to visit a number of schools, among

them Uechi-ryu and Shorin-ryu dojos (schools) that taught the toe kick.

By this time I had practiced the kicks for quite a few years.

My friend and senior in Kyokushin in Japan (who also taught in Oyama’s

absence), who later founded his own style Seido Juku Karate, Tadashi

Nakamura (my teacher), found toe kicks along a different path.

It was the year before I arrived in Tokyo. Mr. Okada, one of Mas Oyama’s

senior students, arranged a meeting between Oyama and an Okinawan karate-ka

friend. Nakamura also attended. After some discussion, they decided to

compare kumite techniques.

|

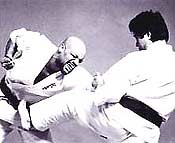

Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura strikes

upward with a short rounded snap toe kick into the lower abdomen

as he pulls his opponent forward.

|

Even at the young age of 17 or 18, Nakamura was an exceptionally strong

fighter. A few years later he represented Kyokushin as part of a three

man team that traveled to Thailand to face the best of their Muay Thai

fighters (boxing type punches mixed with powerful low round kicks) and

Nakamura beat Thailand’s Light Heavyweight Champion. His technique

was tremendous – fast, hard and powerful. When we used to fight

in Japan, I would joke that it felt like his roundhouse kick had been

surgically implanted in my chest, since he had used that technique on

me so often.

Nakamura recounts that when he fought the Okinawan, he was hit low in

the abdomen by a sharp, penetrating front kick. “After that I paid

close attention to what the Okinawan was doing,“ recounts Nakamura. ”He

was a small guy, but he had his own unique kind of kumite. He used low,

short front kicks and roundhouse kicks using his big toe. His front kicks

were sort of like kekomi (thrust kick).”

This made an impression. Soon afterwards, Nakamura was conditioning

his own toes and experimenting with the kick. When Kaicho Nakamura founded

his own Seido Juku karate in 1976, the technique became part of its official

curriculum (5), but in reality this kick is now only taught to few select

students willing to spend the time to condition their toes.

|

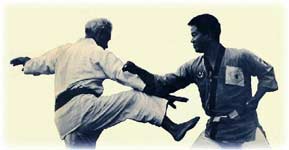

Akira Nakamura Sensei,

son of Seido Juku’s founder, demonstrates a high roundhouse

toe kick while blocking a front toe kick from the author, Christopher

Caile Shihan, during a practice session at the Seido headquarters

in NYC. Historically, however, toe kicks used for self-defense

and as seen in the original versions of most kata were generally

targeted to the lower half of the body.

|

I didn’t realize that Kaicho Nakamura actually practiced this

kick. At the dojo one day, however, Nakamura, his son Akira and I began

discussing the topic. We found that we were all practicing the kick.

This eventually spawned the idea for this article. When I started to

research the topic, I realized that by taking up the toe kick, I was

re-establishing a historical link to the past, to the heritage of technique

and to the masters who once practiced it.

The Okinawan Toe Kick Tradition

Karate emerged on Okinawa from a history of secrecy and behind closed

door practice just as the island was entering a period of profound social,

economic and political change.

In 1850, after visiting Okinawa, Commodore Perry forced Japan to open

to the world. This event also unleashed internal political forces and

turmoil that ultimately led to the end of the feudal Tokugawa dynasty

and the emergence of a new Meiji era.

In 1872 the Meiji regime formally incorporated Okinawa into its political

realm, established a new government for Okinawa, and imposed Japanese

language, culture and education on the island’s people (the king

himself was forced into exile to Japan for safe keeping). This ended

the Okinawan feudal class structure (lords of domains). Feudal incomes

were abolished and 20 percent of the population who once were of noble

class, with lands and stipends, fell on hard times (although they did

have the advantage of access to education and some also had political

connections). Many were thereafter forced to work as common laborers.

(6)

If it had not been for a number of notable martial artists who began

demonstrating and teaching karate, who promoted its adoption into the

Okinawan school system, and who later took it to the Japanese mainland,

karate may have been lost to future generations and the world.

Soken “Bushi” MatsumuraIn the 19th century the best known martial artist on Okinawa was Soken “Bushi” Matsumura,

(1809-1901), who became the fountainhead for one of the two major traditions

of Okinawan karate known as Shorin-ryu.

Scholar and bodyguard to the King, Matsumura was an aristocrat who had

traveled to China as an envoy on state affairs. While there, he is said

to have visited several schools of Chinese boxing and studied under the

Chinese teachers Ason and Iwah. It is also said that he visited the southern

Shaolin temple in Fuchou. (7)

There are earlier masters in the Shorin-ryu tradition too, although

many of their names have been lost to history. It is known that Matsumura

studied with Satsunuku Sakugawa (1735-1815), who in turn had studied

with a Chinese diplomat known as Kushan Ku (beginning in 1756) from whose

techniques was formulated several versions of one of karate’s oldest

kata, Kusanku (Kanku), which used a toe kick in its original version

(shown in Part 4). (8)

While I am not aware of any toe kick stories associated with Matsumura

himself, there are stories of his students, including Pechin Ishimine,

Chotoku Kyan, Chome Hanashiro, Anko Itosu, and Nabe Matsumura (or their

students).

One story involves Pechin (a title relating to military and police authority)

(9) Ishimine, a minor student of Matsumura. One night he was on his way

home in the capital city of Shuri. He was climbing a hill during a drizzling

rain when he encountered a large powerful man known as Tamanaha, who

had been resting. The two struck up a conversation, and continued their

journey together. Recognizing Ishimine, Tamanaha who was obviously a

bit of a rebel- rouser, sought to provoke a fight. First, Tamanaha opened

up an umbrella and then ask Ishimine to hold it, which he did. Getting

no response, next Tamanaha ask Ishimine to hold his muddy straw sandals.

Finally angered, Ishimine threw them over a nearby hedge. Thus, a fight

was started. Tamanaha attacked with a strong punch, but Ishimine quickly

dodged to one side and ended the encounter with a quick toe kick to the

attacker’s lower rib cage. Tamanaha fell to the ground, unconscious.

Not wanting to leave him there, Ishimine then threw the unconscious body

over his shoulder and took him home. (10) Tamanaha, however, died a few

days later.

|

|

|

Another story involves Chotoko Kyan (1870-1945), (11) another student

of Matsumura, as well as a student of Yara Piechan whose grandfather

had also studied with Kushan Ku. A story of Kyan’s student, Ankichi

Arakaki (and later a student of Chibana) is told in Part 4. Kyan was

the teacher of many famous karate-ka including Shoshin Nagamine (Matsubayashi-ryu),

Taro Shimabuko, Eizo Shimabuki (Shorin-ryu-Shaolin) Zenryo Shimaburo

(Chubu Shorin-ryu) and Tatsuo Shimabuko (founder of Isshin-ryu).

Kyan was small and thin, very quick and evasive, and also for his kicking

ability. Well aware of the dangerous potential of karate technique, Kyan

often warned his students about the danger of actually fighting with

karate. He would say, if two young saplings are banged together only

the bark is damaged, but if two fresh eggs are rolled together they will

crack open. (12)

Shoshin

Nagamine, a student of Kyan (founder of Matsubayashi-ryu karate),

demonstrating a toe-kick/punch combination from the kata

Gojushiho. Jeff Brooks a Matsubayashi karate teacher (Sensei) notes

that there are several application, such as a punch to the solar

plexus or alternately gall bladder 24 (at the 7th intercostal space

below the nipple) with a flowing grab (holding the opponent in

place), and a toe tip kick used for deep penetration into a yin

organ, such

as, in this case, the liver. This is a deadly force application,

Brooks notes, that should never be applied in a training setting

nor under any circumstances where deadly force is not warranted. Shoshin

Nagamine, a student of Kyan (founder of Matsubayashi-ryu karate),

demonstrating a toe-kick/punch combination from the kata

Gojushiho. Jeff Brooks a Matsubayashi karate teacher (Sensei) notes

that there are several application, such as a punch to the solar

plexus or alternately gall bladder 24 (at the 7th intercostal space

below the nipple) with a flowing grab (holding the opponent in

place), and a toe tip kick used for deep penetration into a yin

organ, such

as, in this case, the liver. This is a deadly force application,

Brooks notes, that should never be applied in a training setting

nor under any circumstances where deadly force is not warranted.

|

Shoshin Nagamine in his book “The Essence of Okianwan Karate-Do” (p.

40), comments that his teacher Kyan had mastered the secrets of karate

necessary for a small man to face a larger opponent – not to step

backward, but instead to step forward or to the side so to be able to

take offense (kick or punch) right after defending himself. To perfect

this ability Kyan used to train on the banks of the Hija River, keeping

his back to the water.

In 1930, when Kyan was around age 60, while he was giving a demonstration

of karate on the island of Taiwan (now The Republic Of China, known as

free China), a Judo instructor from the Taipei (the island’s capital)

Police Headquarters, Shinjo Ishida, issued Kyan a challenge. Kyan reluctantly

accepted. He was concerned that he would be gripped by his uniform’s

jacket and thrown, so he wore only a vest. Ishida himself was also apparently

wary of Kyan’s striking techniques – so the two sized each

other up, keeping their distance. At some point, however, Kyan quickly

moved in, shot out his arm and thrust his thumb into the side of his

opponent’s mouth. Gripping his opponent’s cheek, Kyan then

kicked Ishida’s knee, which downed him, and Kyan finished with

a knelling punch into the solar plexus. While the type of knee kick is

not mentioned, a toe kick to the inside of the thigh just above the knee

is known to collapse the leg, which is exactly what was reported. Anyway,

it is a good story. (13)

Another student of Matsumura was his grandson, Nabe Matsumura, who in

turn taught only one student, the famous Hohan Soken (1861-1972 and founder

of Matsumura Seito Hakutsuru Shorin Ryu Karatedo & Kobudo). Soken

ultimately became an Okinawan legend and one of the most respected teachers

of his day. Only after 10 years of study, however, did Nabe begin teaching

Soken his hidden family style, the White Crane kung fu style within a

style.

|

|

In rare 8 mm film footage, Soken is seen (left)

doing a technique from his family’s Hakutsuru, or White Crane kata.

At right Soken demonstrates this same technique against his student

Fusei Kise. He moves almost effortlessly off center while lifting

his arm like a wing to ward off and lift upward a punch. This opens

a path for the accompanying toe kick. The technique as performed

seemed soft, pliable and almost effortless as compared to the usually

much harder, ridged looking karate technique. (Complements of Charles

Garrett & Jessy Hughes) |

Like many other former Okinawans of Noble class, Soken teacher Nabe

had been reduced to working in the fields. Soken emigrated abroad in

1920 to find employment (he also refused to learn the new Japanese language),

and ended up in Negro, Argentina where there was an Okinawan trading

colony. There he worked as a photographer, and on a limited basis he

taught karate. (14) When he returned to Okinawa in 1952 many considered

his kata and technique “old style” (in the interim Okinawan

karate had evolved). When Soken began teaching, he taught a few students

privately in his home, but also sometimes visited classes run by his

student Fusei Kise, conducted on the nearby Kaneda Air Force Base.

It is often said that Soken taught an “Old Man’s Karate” not

because it resembles what an old man would do, but rather that it would

take many years of practice. Thus a student would be an old man by the

time he mastered it. He used subtle redirection of attacks, precise timing,

body movement, and control of distance, combined with knowledge of where

to strike and the use of simultaneous technique. Overall he was very

fluid as opposed to the more rooted and hard technique of some Naha-te

styles such as Goju-ryu and even Anko Itsou’s Shorin-ryu (see Part

4).

Soken taught kata, but also kata applications and torite techniques

(grasping and restraint techniques he used as part of block and counter),

including those from his White Crane. His grabs, holds and attacks (often

using a toe kick) were targeted to pressure points.(15) Several students

recounted Soken showing them an old hand printed rice paper book handed

down from Nabe showing pressure points and technique. (16)

|

Roy Suenaka Sensei, a long time student of Soken, demonstrates

one of Soken’s White Crane torite techniques – moving

forward, off line, while executing a simultaneous parry, the same

hand also controlling the punching arm while countering with a

combination finger strike to the neck and toe kick to the knee

area. White Crane

techniques always used open hands. (17) |

In December 1994 I visited Okinawa with Roy Suenaka Sensei, my aikido

teacher who also teaches Matsumura Seito Hakutsuru Shorin Ryu Karatedo).

Suenaka was a private student of Soken from 1961-1972 while serving in

the armed forces and based on Okinawa.

Soken’s favorite toe kick, according to Suenaka, included points

on the inside of the upper leg, the arm pit (if the arm was captured),

solar plexus, ribs, up under the arm (in certain situations if the arm

could be immobilized), the abdomen, and the floating ribs. Another student

of Soken notes that Soken would often say “No kick groin” (his

English was very limited) and instead would aim the kick into the inside

of the upper leg or calf area (virtually never higher than the pelvic

area). (18)

Phillip Koeppel (founder of his own international karate organization

and Director of the United States Karate-Do Kai), who has studied with

Fusei Kise, Yuichi Kuda and Kousai Nishihira (19), students of Soken

who continue the Soken Matsumura Seito Shorin Ryu tradition, agrees with

these targets, He adds that Soken also liked to press or stab his big

toe down onto the top of the foot near the big toe. This can be very

surprising and also painful.

When kicking, Soken did not seemingly use much hip power (the hips were

not extended forward into the kick). He would often punch first, letting

the defender become involved in trying to block this technique, then

let the toe kick come up under it, unseen (not telegraphing it with a

body shift of hip movement). He also liked to use his knees to strike.

(20)

When performing the toe kick Soken sometimes used a triangle of his

big toe, second and third toe, and at other times he just kept his toes

in natural position, squeezed together, remembers Suenaka.

As to Soken’s torite techniques, Suenaka notes that when Soken

performed these techniques, he didn’t get too close to the opponent

(outside grappling range). “The opponent was always kept at a distance,

at arms length, but controlled,” says Suenaka. And while many torite

and countering punch techniques used an extended knuckle (rather than

just a regular fist), White Crane techniques always use open hand finger

counter techniques (such as demonstrated by Suenaka above).

Soken also practiced a number of parry/counter type combinations, says

Suenaka, which he summarized in the saying, “Uki Ti Boom” (Uki

being the Okinawan pronunciation for “uke,” a term indicating

the person initiating a technique in a two man drill and who would be

on the receiving end of the counter, and “ti” the pronunciation

for “te” meaning hand). When an attacker used a straight

punch, for example, the punch was slightly deflected by one arm (combined

with a small shift off line) into the grasp of the second while the first

continued onto target without any visible hesitation in the forward block/counter

punch arm. The technique is very sophisticated, fast, simultaneous and

powerful –letting the forward momentum of the attacker run into

the counter—doubling its power.

|

|

Here the author demonstrates Soken’s

torite as taught by Suenaka, a simultaneous parry combined with

a nukite finger

tip strike into the opponent’s neck which would strike not

only the central bundle of nerves leading to the arms (brachial

plexus) but also the carotid sinus, which helps control blood pressure

(most

likely producing unconsciousness)(21) Using this technique Suenaka

prefers to follow-up with an arm bar. The author demonstrates an

alternative (photo right), a toe kick to the opponent’s back

leg and back-hand strike (reminiscent of one found in the original

versions of both kanku/ kusanku and the pinan series). An arm break

can be added. (22) |

Karate-ka should also note that the technique demonstrated in these

photos almost exactly follows the arm movement in a basic inside block.

This illustrates how some advanced applications can be hidden within

basic movements of kata.

|

|

One toe kick option found in Old Okinawan karate such as that of

Hohan Soken, as well as many Chinese arts, is to capture an extended

arm and then kick upwards (ankle bent) with the toes to the inside

of the upper arm. The target is the axillary nerve (part of the brachial

plexus). A direct hit can paralyze the arm, stun or even cause unconsciousness

(this is a very dangerous technique since it directly targets a nerve,

which if damaged can cause permanent incapacity). An alternate target

is to strike up into the armpit which targets the bundle of nerves

leading from the neck down into the arm (higher up into the brachial

plexus) which can disable the arm, but also cause unconsciousness,

even death. (23) |

Another application of the toe kick to the groin

is when an opponent's

kicking leg has been captured. The target can be the testicles,

but more often the target was a point behind them, the kicking

toes aimed

upward. The opponent's leg can also be lifted

to unbalance or to throw the opponent backward. |

Author’s Note To Readers: This article series represents the author’s

personal experience. While I have added historical references and information,

it does not claim to give a full representation of any specific art or

karate style’s strategy or technique. Likewise, some styles and

masters have undoubtedly been overlooked. More coverage is given to styles

and teachers about which there is personal knowledge. The goal is not

to provide a full historical accounting of toe kicks, but to provide

accounts, information and anecdotes that together will give the reader

a fuller appreciation of the place of toe kicks within the historical

context of karate.

Disclaimer: This article is for educational purposes only. The intent

of this article is to provide information on the historical roots of

the technique and practices related to the development and methods of

early karate and related arts. It is not the intent for the content of

this article, or techniques demonstrated or discussed herein to be practiced

or adopted within the curriculum of present day martial arts practice.

The techniques described and illustrated may seriously harm an opponent

or training partner and readers are not encouraged to use or practice

them. If the reader wants to perform any martial art technique he or

she is advised to do so only with proper supervision and training of

a qualified instructor or teacher certified within the art to be practiced.

Footnotes:

(1) Dan Smith a high ranking Seibukan karate

who lived and studied on Okinawa for many years gives this representation

(of Naha-te and Shuri-te)

as one often used on Okinawa. His style traces its lineage to Chotoku

Kyan through Zenryo Shimabukuro, whose son, Zenpo Shimabukuro how heads

the organization based on Okinawa. Just as Shuri-te became better known

as Shorin-ryu, Naha-te also became widely known as Shorei-ryu, but this

author has used Naha-te within the article. Both names (Shorin-ryu and

Shorei-ryu) appeared in a report written by Anko Itosu in 1908 which

described Okinawan karate for the Okinawan government. Kanryo Higaonna

(see part 4), however, might have been the first to use the term (meaning “The

Style of Inspiration” in one translation). He probable he wanted

to call attention to his style’s Fujian origin (notes John Sells

in his book, “Unante-The Secrets of Karate, 2nd Edition”,

p.47.), for in the Bubushi (a White Crane martial arts manual that was

much valued among early Okinawan karate practitioners) mentions Shorei-ji

(the southern Shaolin temple) – see the articles “Enter The

Bubishi, Part 1 & 2” by Victor Smith in FightingArts.com’s

Reading Room under “History And Historical Influences. A translation

of this book, titled The Bible of Karate: Bubushi”, Translated

with commentary by Patrick McCarthy also appears in FightingArts.com

E-store under “Books” in the Category of “Karate.”

(2) In the Pinan series toe kicks were used

in Pinan 2 and 4 (where Japanese styles now do a backfist or tettsui

along with a simultaneous

side kick).

In Pinan 3, where many Japanese styles do a front kick or crescent kick

from a horse stance following a backfist, this kick was originally not

part of the kata, but instead it was considered an optional technique.

Pinan 5 has a crescent kick. In all the kata, however, many techniques

include the option of using a toe kick, such as when in a back leaning

or cat stance. Also in Pinan 1 or 2 (depending on the style), where the

practitioner does a series of steps doing either a middle punch or upper

block, toe kicks were also an option. Many of the original movements

in the Pinan kata, such as toe kicks, have been changed or modified.

The Pinan kata too seem to be modifications of earlier kata. Although

Anko Itosu is credited as the creator of this kata, many trace them to

an earlier kata, or series of exercises known as Channan. See the article, “Channan:

The "Lost" Kata of Itosu?” by Joe Swift in FightingArts.com’s

Reading Room under the Category “Kata And Applications.” Ernie

Estrada, the well known Shorin Ryu stylist and historian, also suggests

that Pinan 1 and 2 can be traced to Bushi Matsumura.

(3) Kyokushin is a hard style stressing powerful

technique and contact free fighting. In his home Oyama had a small

desk and behind it was a

bookcase crammed with martial arts books from Japan and some from China.

When, at times, I was invited to his home after practice, with his wife

and daughters we would sit around a table (round with a warm comforter

type cloth that could be draped over your legs and a sunken place for

your feet) where we would eat and then discuss many things – technique,

karate, history, etc. It should be noted that Oyama’s English was

poor and my Japanese worse, so discussion was difficult. He showed me

pictures in some of these books and asked what I thought. Some of these

thoughts and research, I think, were later seen in his book “Advanced

Karate.” In his style, Oyama added circularity to his blocks and

adopted low Thai style round kicks to the legs (excellent for freefighting).

He also created kata and modified others too (even adding what I see

as an aikijujutsu technique to Pinan 2). But while Oyama was thus innovative

in his thinking and willing to adopt technique that worked, toe kicks

were never discussed or used. During the months that he was working on

taking photographs for his book, “This Is Karate,” I spent

several evenings a week working with him on the photo sections, and many

photos were taken of our choreographed freefighting. In between he would

often ask me to attack him this way or that, or we would lightly trade

techniques – and while he used many techniques and kicks, I never

saw a toe kick.

(4) See the article, “Kata As The Foundation Of Practice” by

Christopher Caile in FightingArts.com Reading Room under the category “Kata

And Applications.”

(5) See Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura’s book, “Karate –Technique

and Spirit.” On page 82 he shows the toe technique executed on

a student. In class, however, the toe kick is not taught.

(6) Japan imposed Japanese as the official language (rather than the

previous local language, known to many a Hogan, meaning dialect, but

which is more precisely known as Uchinada Guchi). New schools were opened

to teach Japanese both as a language and culture. Chinese culture and

education which once predominated was now marginalized. At the same time

Okinawans were for the most part very poor, most were illiterate, and

Okinawa itself was considered by most of the outside world as a marginal

entity with few natural resources.

(7) The existence of a southern Shaolin temple

is much disputed. Even though many make reference to it, its physical

ruins have yet to be located.

The name Shaolin, however, was famous from its association with the Northern

Shaolin temple (the birthplace of Zen under the Chinese monk Bodhidarma)

from which many Chinese martial arts trace their origin. Thus, the attribution

of Shaolin (or Shaolin temple) to a style was often used to enhance prestige.

One source suggests that the southern Shaolin temple was a central temple

in Nansoye, a little to the south of Fuchou, and the term Nansoye Shaolin

temple was actually a cover for a secret society who had fled persecution

in the North. See: Mark Bishop in his book “Okinawan Karate,” 2nd

edition, p39.

(8) Satsunuku Sakugawa (1735-1815) is best

known as “Tode” Sakugawa

(“to” being an Okinawan term referring to the Tang period,

meaning China, and “de” another pronunciation for “te”,

a term meaning hand or fighting art, which we now call karate). Sakugawa

first studied with Peichin Takahara (1683-1760), who had also studied

in China while acting as an official of the Shuri government and mapmaker.

In 1756 Sakugawa met and then started studying with a Chinese diplomat

Kushan Ku (or Kung Shang Kiung) and learning Chinese kempo. Kushan Ku’s

techniques are said to be embodied in one of karate’s oldest and

best known kata, Kusanku, or Kanku. It is also said that Matsumura studied

with a ship wrecked Chinese sailor from which studies he devised the

kata Chinto. Before these masters, there were undoubtedly many others

going back several hundred years, but their names have not survived.

Some historians suggest that Kusanku actually taught kumiuchi-jutsu,

which means fighting or grappling arts. One source suggests that Kusanku

introduced the concept of hikite, meaning pulling or drawing hand to

Okinawan. See: John Sells, “Unanate –The Secrets of Karate,” 2nd

Edition, p. 25.

(9) In the old Okinawan kingdom the noble class

was structured into levels. On top was the king and extended family,

under them were

local lords (originally known as anji), and below this level of princes

were influential political retainers known as Oyakata (ministers and

other high ranking government posts) which in turn were subdivided – the

king’s Council (Sanshikan) at top, then a series of ranks relating

to magistrates, attaches, constables and bodyguards collectively known

as Peichin (military and civil police authorities). See: Jophn Sells. “Unante-The

Secrets of Karate (2nd edition), p. 9

(10) Bishop. Bishop reports that Ishimine is today little

remembered on Okinawa, but some sources suggest that he was actually

Ishimine Peichin, who had at one time been a student of Matsumura. Today

on Okinawa there is a style, Ishimine-ryu, headed by Shinyei Kaneshime,

which is named after him.

(11) Kyan’s father was the steward to

the last Ryukyu (Okinawan) king Sho Tai and accompanied him into exile

in Tokyo. Chotoku also lived

in Japan, where he was educated. Returning to Okinawa he studied with

several teachers including Matsumura (from whom he learned the kata Sesan,

Naihanshi and Gojushiho). He learned the Kusanku (Kanku) kata from Yara

Peichin, the grandson of Yara Chatan (a contemporary of Sakugawa who

had also studied with Kushan Ku), from which lineage came Yara Kusanku,

a unique version this kata. Kyan also learned several other kata from

Tomari-te stylists. Thus, Kyan while often classified as a Shorin-ryu

stylist had Tomari-te influences as well.

(12) “Okinawan Karate,” ( 2nd Edition) by Mark Bishop, p.

74. Nagamine in his book “The Essence Of Okinawan Karate-Do”(p.

40) notes that the Kyan family with the Meiji political reform had also

lost their economic support and social privilege and had to struggle

for existence.

(13) As recounted in part 2 of a three part

article titled “Masters

of the Shorin-ryu” by Graham Nobel with Ian McLarenand and Prof.

N. Karasawa which appeared in Fighting Arts International, Issue No.

51, Vol. 9, No, 3 1998 p. 33. Others, however, question the use of the

toe kick in the story. Dan Smith a high ranking member of Seibukan which

descended from Kyan, discounts the use of a kick altogether. This only

shows the conflicting nature of the oral tradition of karate that exists

on Okinawa today.

(14) Ernie Estrada, the respected Shorin-ryu

practitioner and karate historian, conducted a series of interviews

with practitioners who trace

their roots of Soken in Argentina. When he emigrated Soken had been given

private lessons in Matumura Karate by his uncle, Nabe Matsumura, but

he was not a member of an organization, nor had he been extended rank.

According to Estrada’s research, in the Argentine community karate

was taught in a community dojo; various people taught, with Soken among

them. After he left, his few students were absorbed by others still teaching.

Photos of his demonstrations in Argentina, it should be noted, still

exist.

(15) Soken would strike to vital points using

both hands and feet. He also often demonstrated to visitors the use

of his thumb to strike these

targets “which were very painful,” recounts Ernie Estrada,

the well known Shorin-ryu teacher and karate historian, who conducted

a series of interviews with Soken over the years. The techniques, taken

from old Okinawan “ti”, are reminiscent to those used by

Sean Connery in the 1988 movie “The Persidio” where he plays

Lt. Col. Alan Caldwell. Caldwell investigates a murder on his air base,

and in the process ends a number of physical confrontations using just

his thumb for a weapon.

(16) One account was given by Charles Garrett

who studied with Soken on Okinawa over a period of two years. The name

of the book in

not known. It could be a copy of the Bubushi, but Garrett thinks that

the book originated with Matsumura himself who passed it down to Nabe

Matsumura. Roy Suenaka who studied with Soken longer than any other foreign

student also remembers a similar book – rice paper pages filled

with characters and diagrams with points. Suenaka says that Soken rarely

showed this book to others and over 10 years he had only been shown it

a couple of times.

(17) The forward movement seen above is also

characteristic of karate kata and is optimally suited to self-defense

situations where

control of the initial technique is the goal. Student’s of Seido

Juku might also recognize a parallel with Seido strategy. A similar strategy

of entry is also shared by other martial arts. It is often used in aikido,

notes Suenaka, as well as other jujutsu arts, although in aikido the

technique is continued differently into a joint manipulation or throw.

The use of atemi is also different.

(18) Interview with Charles Garrett. Garrett

who studied with Soken for during the 1970-1972 time period. “He also used his back

leg for these kicks,” adds Garrett, and “just before contact

he would tighten his body (but not his leg) in order to extend power

through the leg.”

(19) Koeppel (10th dan, and a famous early

karate pioneer) has produced an excellent tape series detailing his

Matsumura kata experience.

It was originally produced for senior students, but is now offered to

the public. See: Matsumura Seito Shorinryu: Secrets Of Kata Video Series

(6 videos) in FightingArts.com E-Store Video category under “Kata

and Applications.” It is one of the most educational tape series

now available. Koeppel was this author’s first teacher beginning

in 1959 in Peoria, Illinois. Originally Koeppel taught Kempo Karate,

and later became associated with Robert Trias. Interested in the roots

of karate, he later visited Okinawa and adopted the Matsumura style,

which he has now taught for many years under the tutelage of Fusei Kise,

Yuichi Kuda and currently Kousai Nishihira.

(20) Interview with Charles Garrett.

(21) Although I have never studied karate with Suenaka, I have been

his aikido student of his since 1990 (first studying with Shihan Mike

Hawley in Buffalo, New York). During seminars, winter and summer camps

I have prompted him to teach torite and other hand techniques, those

which he learned from Soken. He has been very obliging, thinking that

learning to punch is also important for his aikido students to learn

(22) There is also a secondary technique hidden

within the above sequence. If the defender moves in slightly closer

to the body of the opponent

while doing the backhand/toe kick counter, another technique can be added.

The opponent being off balanced by the kick while his head is snapped

back responds automatically – the body’s reflex mechanism

kicking in – and the arms straighten and extend in an effort to

regain balance. With the captured arm positioned across the defender’s

chest, if the stomach is flexed outward against the elbow, the elbow

can be easily damaged or broken.

(23) See the article “What's The Point? Speculations On

the First Move From Pinan Kata Two, Pressure Points And The Reality Of

The Death Touch” by Ronald van de Sandt in FightingArts.com’s

Reading Room under the category “Pressure

Points.”

About The Author:

Christopher Caile is the Founder and Editor-In-Chief of

FightingArts.com. He has been a student of the martial arts for over

43 years. He first started in judo. Then he added karate as a student

of Phil Koeppel in 1959. Caile introduced karate to Finland in 1960 and

then hitch-hiked eastward. In Japan (1961) he studied under Mas Oyama

and later in the US became a Kyokushinkai Branch Chief. In 1976 he followed

Kaicho Tadashi Nakamura when he formed Seido karate and is now a 6th

degree black belt in that organization's honbu dojo. Other experience

includes judo, aikido, diato-ryu, kenjutsu, kobudo, Shinto Muso-ryu jodo,

boxing and several Chinese fighting arts including Praying mantis, Pak

Mei (White Eyebrow) and shuai chiao. He is also a student of Zen. A long-term

student of one branch of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Qigong, he is

a personal disciple of the qi gong master and teacher of acupuncture

Dr. Zaiwen Shen (M.D., Ph.D.) and is Vice-President of the DS International

Chi Medicine Association. He holds an M.A. in International Relations

from American University in Washington D.C. and has traveled extensively

through South and Southeast Asia. He frequently returns to Japan and

Okinawa to continue his studies in the martial arts, their history and

tradition. In his professional life he has been a businessman, newspaper

journalist, inventor and entrepreneur.

|