Yoshida Shoin:

The Archetype of Japanese Revolutionaries

By Romulus Hillsborough

Editor's

Note: This is the third article on famous Japanese Samurai

leaders who, at the end of Japan’s feudal period, defied death

and personal safety to help forge a new Japan. Prior articles included “Sakamoto

Ryoma: The Indispensable Nobody” and "Katsu Kaishu: The Man

Who Saved Early Modern Japan." Yoshida Torajiro (best known by his

pen name Shoin), the subject of this article, was a principal intellectual

protagonist of the Meiji Restoration of 1868 whose heroism and writings

brought him much acclaim He was one among a group of Samurai leaders

drawn from various clans whose beliefs, statesmanship and actions instigated

dramatic changes in Japan following Commodore Perry’s naval intrusion

-- the overthrow of the military government (1868), institution of a

parliamentary government, and modernization – that virtually overnight

turned a feudal society toward a progressive modern age.

If

the tenet of certain age-old philosophies is true that the physical

environment at birth has an ominous effect on the future personality

and life of the newborn child, then perhaps it was the sweltering

heat of the Hagi [referring to the castle down of Hagi - ed.] summer

that lit the flame of passion in Yoshida Shoin’s indomitable

spirit for a new and stronger Japan — a passion which would

neither be extinguished by the cold steel of the executioner’s

sword some twenty-nine years later, nor by the passing of nearly

one century and a half since his tragic death. For not only has Choshu’s

[one of the principal military domains in feudal Japan - ed.] most

beloved samurai been immortalized in the annals of Japanese history,

but his spirit has been sanctified in numerous hagiographies [literally

meaning the biography of of a Saint, but here used to refer to

biographies of Shoin by others - ed.] his lofty aspirations recorded

in copious

biographies, his memory canonized in paintings and statuettes which

to this day grace the alters of countless homes throughout the

Yamaguchi countryside [the modern Yamaguchi prefecture that replaced

the Choshu

domian - ed.] where the charismatic genius came into this world. If

the tenet of certain age-old philosophies is true that the physical

environment at birth has an ominous effect on the future personality

and life of the newborn child, then perhaps it was the sweltering

heat of the Hagi [referring to the castle down of Hagi - ed.] summer

that lit the flame of passion in Yoshida Shoin’s indomitable

spirit for a new and stronger Japan — a passion which would

neither be extinguished by the cold steel of the executioner’s

sword some twenty-nine years later, nor by the passing of nearly

one century and a half since his tragic death. For not only has Choshu’s

[one of the principal military domains in feudal Japan - ed.] most

beloved samurai been immortalized in the annals of Japanese history,

but his spirit has been sanctified in numerous hagiographies [literally

meaning the biography of of a Saint, but here used to refer to

biographies of Shoin by others - ed.] his lofty aspirations recorded

in copious

biographies, his memory canonized in paintings and statuettes which

to this day grace the alters of countless homes throughout the

Yamaguchi countryside [the modern Yamaguchi prefecture that replaced

the Choshu

domian - ed.] where the charismatic genius came into this world.

|

Yoshida Shoin was born the second son of a lower ranking samurai in

the village of Matsumoto, amidst the verdant foothills of the castle

town of Hagi, center of the great domain of Choshu, by the aquamarine

Sea of Japan, in the eighth month of the first year of the Era of Heaven’s

Protection — or more simply put, August 1830.

|

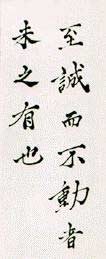

Shoin’s motto and

calligraphy, "Sincerity and perseverance always win," the

dictum borrowed from the Chinese philosopher Mencius.

|

|

“He knew nothing of anger,” a former student would recall. “He

was kind to others… and had a polite manner of speech.” Yoshida

Shoin was physically frail, soft-spoken and a master of self-control

whose willpower knew no bounds. He was an avid scholar who denied himself

sleep, and who was known to stand or walk in the snow to keep himself

awake for his studies. At age five Shoin began the formal study of military

tactics and the Chinese classics. By age eight he was studying the Confucian

philosophy of Meng-tzu, and began attending the official college of the

Choshu domain. In the following year he taught at the college. At age

ten he won praise from the Lord of Choshu for his recital of the military

classics. At fifteen he became awakened to the dangerous goings on in

the world outside the sacred Empire of Yamato [Japan - ed.]. In 1848,

five years before the arrival of Perry, he advised the Lord of Choshu

to prepare

for foreign invasion. In 1851, his twenty-first year, Shoin accompanied

the Lord of Choshu to the Shogun’s capital at Edo [now Tokyo -

ed.], where he studied under Sakuma Shozan, the most celebrated Western

military scientist in Japan.

Shoin was in Edo when Commodore Matthew Perry of

the United States Navy arrived in June 1853. Perry led a squadron of

heavily

armed warships

into the bay off the Shogun’s [the military leader of Japan who

was during this time the head of the Tokugawa clan - ed.] capital, demanding

an end of Japanese isolation and inciting fifteen years of

bloody turmoil throughout the island nation.

Shoin learned from Shozan

the futility of challenging the modern military power of the West with

Japan’s ancient arts of war. He adopted his teacher’s belief

in the aphorism “Know the enemy” in order to “control

the barbarians through barbarian technology.” But the Tokugawa

Shogunate did not have the wherewithal to reject Perry’s demands.

Rather than remain idle while bumbling Tokugawa officials sealed the

fate of the Japanese nation, Shoin, with the help of his revered teacher,

planned drastic measures.

|

Commodore Perry

|

|

|

Perry’s first landing

on Japanese soil

|

|

Perry concluded Japan’s first treaty with the United

States in March 1854. Shortly after, his squadron lay in the harbor at

Shimoda,

one of two ports opened under the terms of the treaty, from which it

would soon depart.

Shoin prepared a letter for Perry, which he and a fellow Choshu samurai

delivered to American officers on land, under the cover of night. Perry

described the incident: [They] “were observed to be men of some

position and rank, as each wore the two swords characteristic of distinction,

and were dressed in the wide but short trowsers of rich silk brocade.

Their manner showed the usual courtly refinement of the better classes,

but they exhibited the embarrassment of men who evidently were not perfectly

at their ease, and were about doing something of dubious propriety. They

cast their eyes stealthily about as if to assure themselves that none

of their countrymen were at hand to observe their proceedings, and then

approaching one of the officers and pretending to admire his watch-chain,

slipped within the breast of his coat a folded paper.”

The “folded paper,” written in “the mandarin Chinese

with fluency and apparent elegance,” and translated by Perry’s

interpreter, was as moving in its humble tone as it was compelling. “Two

scholars from Yedo, in Japan, present this letter for the inspection

of ‘the high officers and those who manage affairs.’ Our

attainments are few and trifling, as we ourselves are small and unimportant,

so that we are abashed in coming before you; we are neither skilled in

the use of arms, nor are we able to discourse upon the rules of strategy

and military discipline… we have been for many years desirous of

going over the ‘five great continents,’ but the laws of our

country in all maritime points are very strict; for foreigners to come

into the country, and for natives to go abroad, are both immutably forbidden. “…we

now secretly send you this private request, that you will take us on

board your ships as they go out to sea.”

|

The USS Mississippi

|

Although Perry would never

know Yoshida Shoin’s name, his identity

or his ultimate fate, he was sufficiently impressed by the idealistic

young man’s bold attempt to defy “the eccentric and sanguinary

code of Japanese law,” to record an account of it: “During

the succeeding night, about two o’clock a.m… the officer

of the midwatch, on board the steamer Mississippi, was aroused by a voice

from a boat alongside, and upon proceeding to the gangway, found a couple

of Japanese, who had mounted the ladder at the ship’s side, and

upon being accosted, made signs expressive of a desire to be admitted

on board. “They seemed very eager to be allowed to remain, and

showed a very evident determination not to return to the shore.”

Refused by Perry, the two samurai were apprehended by the Japanese authorities,

and confined to a cage. They nevertheless managed to relay a message

to the Americans, “a remarkable specimen of philosophical resignation

under circumstances which would have tried the stoicism of Cato…[the

ancient Roman statesman and politician - ed.]” The message begins: “When

a hero fails in his purpose, his acts are then regarded as those of a

villain and robber. In public have we been seized and pinioned and caged

for many days… Therefore, looking up while yet we have nothing

wherewith to reproach ourselves, it must now be seen whether a hero will

prove himself to be one indeed.” Shoin’s heroics would become

self-evident soon enough, but first he would be transported to the jail

in Edo, and returned as a prisoner to Hagi.

|

Towsend

Harris

|

In summer 1856, American envoy Townsend Harris of the United States

established the first American Consulate in Japan at a Buddhist temple

in Shimoda to negotiate Japan’s first commercial treaty. Protocol

demanded that the shogunate could only sign a treaty after receiving

permission from the Imperial Court at Kyoto. As a commercial treaty with

the United States materialized, opposition grew among proponents of Expelling

the Barbarians, who now rallied around the Kyoto court.

|

Il Naksuke

|

These xenophobes

called themselves Imperial Loyalists. Pitted against them were the

proponents of Opening the Country, led by Ii Naosuke, the powerful

Lord of Hikone

[the feudal domain - ed.]. Japan split into two factions.

The Loyalists claimed that the Shogun was merely an Imperial agent,

who at the beginning of the seventeenth century had been commissioned

by the Emperor to protect Japan from foreign invasion. They claimed that

true political authority rested with the Emperor, and that the Tokugawa

could only justify its rule by expelling the foreigners. They argued

that since the Shogun was no longer capable of fulfilling this ancient

duty, the Emperor and his court must be restored to power to save the

nation. As a result, the national government developed into a twofold

structure: while the shogunate continued to rule at Edo, the Imperial

Court was undergoing a political renaissance in its ancient capital at

Kyoto.

When the Edo authorities petitioned Kyoto to sanction the commercial

treaty, they were flatly refused. In April 1858, Ii Naosuke was appointed

Tokugawa Regent, making him head of the Shogun’s council and arbitrary

ruler of the military government. In June Regent Ii realized a commercial

treaty with the United States without Imperial sanction, and pandemonium

ensued.

After spending over a year in prison, Shoin was placed under house confinement.

In November 1857, he established his progressive Sho-ka-son-juku – Village

School Under the Pines – and thereby secured his place in Japanese

history.

Shoin On Leadership

What is important in a leader

is a resolute will and determination. A man may be versatile

and learned, but if he lacks resoluteness and determination,

of what use will he be?

*

Once the will is resolved,

one’s spirit is strengthened. Even a peasant s will

is hard to deny, but a samurai of resolute will can sway

ten thousand men.

*

One who aspires to greatness

should read and study, pursuing the True Way with such

a firm resolve that he is perfectly straightforward and

open, rises above the superficialities of conventional

behavior, and refuses to be satisfied with the petty or

commonplace.

*

Once a man’s will

is set, he need no longer rely on others or expect anything

from the world. His vision encompasses Heaven and earth,

past and present, and the tranquility of his heart is undisturbed.

*

Life and death, union and

separation, follow hard upon one another. Nothing is steadfast

but the will, nothing endures but one’s achievements.

These alone count in life. To consider oneself different

from ordinary men is wrong.

|

|

As samurai throughout Japan ranted and raved and vowed to kill the “traitors” who

had opened the country to the “barbarians,” Yoshida Shoin

preached Imperial Loyalism to young men of the lower rungs of Choshu

society at his academy in Hagi. He professed that the Emperor was the

true sovereign of Japan. He opened his pupils’ eyes to the dangerous

situation of the world outside. But Master Shoin nevertheless supported

Tokugawa rule, and favored Opening the Country to enrich the nation and

develop a strong military. He advocated a union between Kyoto and Edo

to protect Japan from the threat of foreign subjugation. These ideas

he instilled in the minds of his young disciples. And he was only twenty-seven

years old. And he was very successful, for among his disciples were future

leaders of the revolution which was the Meiji Restoration, including

two prime ministers.

No sooner had Shoin heard the

news of Ii’s “blasphemy,” than

he made a complete turnabout in his political stance, and became the

most radical of zealots who preached Imperial Reverence and Expelling

the Barbarians. He would now “correct” the lese majesty [affront

to the Emperor - ed.] committed by the evil regent. He would take part

in a plot among radicals from other clans to assassinate him, but first,

in

November 1858, he planned to assassinate a Tokugawa councilor whom Ii

had unsuccessfully sent to Kyoto to obtain Imperial sanction for the

commercial treaty.

Shoin’s plan was never realized, for it was determined by the

Choshu authorities that his radicalism threatened the well-being of their

daimyo (the military leader of their domain). In December Shoin was again

imprisoned in Hagi. But he would not compromise his ideals, and from

his cell became more and more defiant. “I am sorry to say,” he

wrote to a friend, “but I have no use for the Imperial Court, the

shogunate, or our clan. The only thing I need is…my own meager

body.” If neither Edo, Kyoto or Choshu would take the appropriate

measures, then this archetype of Japanese revolutionaries would. The

revolution he envisioned would be accomplished through the cooperation

of lower ranking samurai and men from the peasant and merchant classes.

The notion was preposterous in 1858, but more prophetic perhaps than

even Shoin imagined.

Shoin would not live to see the revolution unfold. In the following

May Choshu received orders from the shogunate to send its most dangerous

insurgent to Edo. Shoin reached Edo in June, was imprisoned there in

July. He was questioned by the authorities, who were amazed by his confessions.

Defiant as ever and determined to set the authorities on the proper course,

Shoin not only openly expressed his disdain for the dictatorship of Regent

Ii and his suppression of the Loyalists, but he took it upon himself

to divulge his assassination plans.

Although Shoin’s confession had sealed his fate, even now he did

not expect to die. He was too occupied planning the revolution. What’s

more, his assassination plans had never been realized, and his confession

had been voluntary. “I don’t know what my punishment will

be, but I don’t think it will be execution,” he wrote to

his family in June. It wasn't until mid-October, when three of his comrades

were executed, that Shoin realized his end was near. On October 15 he

wrote a death

poem. Two days later he was informed of his death sentence. He was brought

to an open courtyard adjacent to the prison, and led to the scaffold.

With perfect composure he kneeled atop a straw mat, beyond which was

a rectangular hole dug in the rich, dark earth to absorb the blood. Standing

nearby was the executioner, Yamada Asaemon, his long and short swords

stuck through the sash at his left hip. Asaemon, who beheaded thousands

during his long, illustrious career, was duly impressed by Shoin. “Yoshida

Shoin died a truly noble death,” he would tell his son.

Shoin calmly straightened his clothes. He asked for a piece of tissue

paper to clear his nasal passage, then recited his final death poem: “Parental

love exceeds one’s love for his parents. How will they take the

tidings of today?” The executioner now drew his long sword, and

with one clean stroke severed the head of the archetype of Japanese revolutionaries.

About The Author:

Romulus Hillsborough is a native Californian who lived in Japan for

sixteen years, studying the language, history and culture. He is the

author of RYOMA - Life of a Renaissance Samurai(Ridgeback Press, 1999)

and Samurai Sketches: From the Bloody Final Years of the Shogun (Ridgeback

Press, 2001). RYOMA is the only biographical novel of Sakamoto Ryoma

in the English language. Samurai Sketches is a collection of historical

sketches, never before presented in English, depicting men and events

during the revolutionary years of mid-19th century Japan. Reviews and

more information about these books are available from Ridgeback

Press.

Also see the Samurai History Tour at http://www.ridgebackpress.com/tour.htm.

For more information about Katsu Kaishu and Sakomoto Ryoma see:

“Ryoma - Life of a Renaissance Samurai”

By Romulus Hillsborough

Ridgeback Press

Hardcover, 614 Pages

RBP-B- 2035

$40.00

(Plus $6.00 Shipping Within US)

|