Throws in Karate?

by Joe Swift

The mere mention of the word "karate" conjures up

many images to the listener, the most common probably

being that of two combatants fighting each other with

kicks and punches. However, this image seems to stem

from the training methods and practices adopted by

modern karate, and is not necessarily a true representation

of the older Okinawan methods. In fact, karate is

more of a complete self defense system than most non-practitioners

realize, incorporating not only strikes, punches,

and kicks aimed at the body's most anatomically vulnerable

areas, but also joint locks, takedowns, throws, strangulations,

restraints, etc.

The mere mention of the word "karate" conjures up

many images to the listener, the most common probably

being that of two combatants fighting each other with

kicks and punches. However, this image seems to stem

from the training methods and practices adopted by

modern karate, and is not necessarily a true representation

of the older Okinawan methods. In fact, karate is

more of a complete self defense system than most non-practitioners

realize, incorporating not only strikes, punches,

and kicks aimed at the body's most anatomically vulnerable

areas, but also joint locks, takedowns, throws, strangulations,

restraints, etc.

This article will focus its attention to one all-but-forgotten

aspect of karate application, namely throwing techniques.

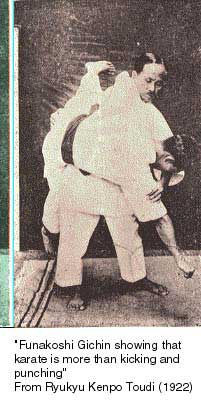

Specific mention of throwing techniques in karate

can be found as far back as 1922, in the first known

published book on the art, Funakoshiís classic Ryukyu

Kenpo Toudi. This book nominated eight throws, with

specific mention that at least two of them were applications

from kata described in the book. Funakoshiís next

two books, Rentan Goshin Toudijutsu (1925) and Karatedo

Kyohan (1935), also contained examples of throws and

takedowns.

One other book worth taking a look at is the 1938

collaborative publication entitled Kobo Kenpo Karatedo

Nyumon by Mabuni Kenwa and Nakasone Genwa. In addition

to describing many throws and takedowns, Mabuni also

states that the karate that was introduced to Tokyo

(Mabuni lived/taught in Osaka) was only a single portion

of a larger whole, and that the fact that people in

Tokyo viewed karate as a solely striking and kicking

art only served to point out their overall lack of

awareness of the complete nature of karate (Mabuni

et al, 1938).

More often than not, throws are not implicit in the

kata techniques, but serve more as follow ups or "exit

techniques" after the necessary set-up, or "entry

technique" has been established through strikes. One

general rule of thumbs for throwing in general is

to first damage the opponent with strikes, so as to

lessen the chances for resistance (Kinjo, 1991).

Senior American karate teacher Dan Smith, who has

spent considerable time learning karate at the "source"

in Okinawa, from numerous teachers, recently observed

the following:

"The question was why didn't the kata show the full

follow through on throws in the kata. I asked the

question while on Okinawa of several senior teachers.

Their unanimous answer was that the throws in Okinawan

karate are not meant to throw the opponent anywhere

but the ground. Secondly, it is not appropriate to

think you can throw someone far when you have already

struck them and at the point of throwing or tripping

them to the ground they should already be headed that

way. . . If you follow the bunkai of the kata the

throws are proceeded by striking techniques, which

should eliminate the ability to off balance the opponent

and use their momentum to throw them very far from

where you are." (Smith, 1999)

Let us now take a look at some specific throws found

in karate kata.

From Kusanku, Passai, Pinan Godan, Seiyunchin, Chinto,

etc.

This particular throwing technique that can be utilized

in response to many types of attack, including a straight

punch to the facial area, a wrist grab, an attempted

lapel or throat grab, etc. Thus, as the method of

entry depends upon what type of attack is being defended

against, this description will not cover a specific

entry into the technique, but rather explain the actual

technique itself.

This technique is actually an application of a position

found in most, if not all, versions of Kusanku, as

well as in Passai, Chinto, Pinan Godan, Seiyunchin,

and several other kata. This posture goes by many

names, such as Manji-gamae, Tettsui-gamae, Ura-gamae,

etc., and comes in many variations. It is represented

by one hand in a low position in front of the performer

and the other hand raised up either above the forehead

or behind the head. Some kata use an open hand, others

a closed fist, and the stance also often changes between

kata and/or variations. However, the fundamental principle

remains the same.

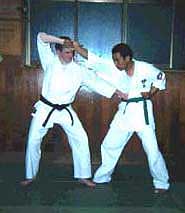

Photograph

1. The application of the posture. The right hand

pulls the opponent's right hand to break his balance

as the left hand strikes into the lower body. Possible

kyusho targets are denko (GB-24) or inazuma (Liv-13).

The idea here is to inflict damage on the opponent

before throwing.

Photograph

2. Step in front of the opponent's right leg, and

slap the testicles with the left hand to inflict more

damage and to get the opponent to bend forward.

Photograph

3. Controlling the opponent's left hand, apply

pressure to the Golgi receptors at the back of the

tricep tendon (kyusho name hiji-tsume, TW-11), and

Photograph

4. Turning the hips to the right, throw the opponent

down. Possible follow ups can include a well placed

strike or kick, a joint lock, or similar technique

of subjugation.

From Kururunfa

This throw is actually described in Mabuni and Nakasoni's

1938 Karatedo Nyumon, page 208. It is an application

against a full nelson hold from behind. Below is an

English translation of the instructions, with accompanying

line drawings from the book.

Ura-nage (Throw to the Rear)

When the opponent grabs you in a full-nelson by inserting

his hands under your armpits, before he can get set,

immediately bring both arms up, backs of the hands

facing each other, and strike down with your elbows

with all your strength (as if performing a descending

elbow smash).

The opponent's grip should loosen, and you should

then head-butt him in the face (if the opponent has

gotten you in a deep full-nelson, your head-butt will

probably strike him in the throat or the chest). Sink

your body down, grab the back of his knees with your

hands, and topple him backwards by striking again

with the back of your head.

Note: Be sure to keep your mouth open when you perform

the rear head-butt, as if you close it, you run the

risk of numbing your eyes (temporary blindness ñ tr).

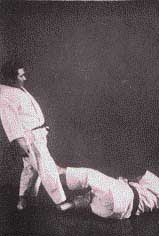

Two

of Mabuni Kenwa (from his 1938 book Karatedo Nyumon)

His partner in the photos is Taira Shinken.

In closing, I would like to share a

personal anecdote. Showing a copy of a Japanese translation

of the Bubishi to my current teacher, we were looking

at the 48 self defense techniques presented therein.

After a few minutes, he looked at me, and said, "Letís

get out on the dojo floor." He proceeded to demonstrate

(on me!) several takedowns and grappling techniques

that were almost verbatim from the Bubishi. I asked

him where he learned them. His reply: "Jujutsu."

Bibliography

Funakoshi, G. (1922) Ryukyu Kenpo Toudi. Tokyo: Bukyosha

(Reprinted edition, 1994, Naha: Yoju-shorin)

Funakoshi, G. (1925) Rentan Goshin Toudijutsu. Tokyo:

Kobundo. (Reprinted edition, 1996, Yoju-shorin)

Funakoshi, G. (1935) Karatedo Kyohan. Tokyo: Okura

Kobundo.

Kinjo H. (1991) Yomigaeru Dento Karate (A Return to

Traditional Karate) Vol 3 (video presentation). Tokyo:

Quest Productions.

Mabuni K. and Nakasone G. (1938) Kobo Kenpo Karatedo

Nyumon. Tokyo: Kobukan. (Reprint edition, 1996, Naha:

Yoju-shorin)

Smith, D. (1999) E-mail Post to Cyber Dojo

Photo Credits:

All old photographs in this article were provided

by Mr. Takeishi Kazumi of Yoju Shorin Bookstore in

Okinawa. I would also like to personally thank my

dojo-mate Mr. Matsumoto, for posing in the other photographs,

as well as my teacher Uematsu Yoshiyuki Sensei, for

the use of his dojo when shooting the photos.

About the Author:

Joe Swift, native of New York State (USA) has lived

in Japan since 1994. He holds a dan-rank in Isshinryu

Karatedo, and also currently acts as assistant instructor

at the Mushinkan Shoreiryu Karate Kobudo Dojo in Kanazawa,

Japan. He is also a member of the International Ryukyu

Karate Research Society and the Okinawa Isshinryu

Karate Kobudo Association. He currently works as a

translator/interpreter for the Ishikawa International

Cooperation Research Centre in Kanazawa. He is also

on the Board of Advisors for FightingArts.com.

back

to top

home

| about

us | magazine

| learning

| connections

| estore

|