Creativity, Bound Flow & The Concept of Shu-Ha-Ri

In Kata

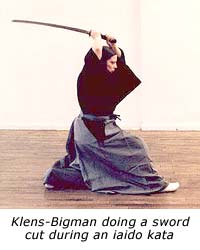

By Deborah Klens-Bigman, Ph.D.

One

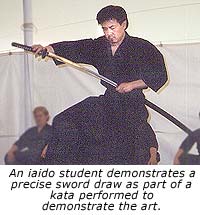

of the questions that often comes up with regard to

my studies in iaido (the art of drawing the sword)

and Nihon buyo (Japanese classical dance) is whether

there is any element of creativity involved in these

very traditional art forms which feature highly stylized

timing and movement. Both are based on the study of

kata, usually translated in the West as "form."

However, the English word "form" does not

begin to explain the complexity of what kata actually

is. Kata, especially in non-sport martial arts, are

patterns of movement which embody techniques and stylistic

elements of a particular art form. Some older martial

arts forms consist almost entirely of kata, with little

"freestyle" movement. One

of the questions that often comes up with regard to

my studies in iaido (the art of drawing the sword)

and Nihon buyo (Japanese classical dance) is whether

there is any element of creativity involved in these

very traditional art forms which feature highly stylized

timing and movement. Both are based on the study of

kata, usually translated in the West as "form."

However, the English word "form" does not

begin to explain the complexity of what kata actually

is. Kata, especially in non-sport martial arts, are

patterns of movement which embody techniques and stylistic

elements of a particular art form. Some older martial

arts forms consist almost entirely of kata, with little

"freestyle" movement.

Kata has been a traditional tool for teaching martial

arts in Japan for centuries and is also prevalent

throughout Japanese traditional arts including, but

in no way limited to, flower arranging, tea, traditional

Japanese dance, and the kabuki and noh theaters.

This article is in part entitled "bound flow"

so as to be able to draw on the insights of Rudolph

Laban (1879-1958), a pioneer in movement analysis.

Laban developed a system that could be used, he hoped,

for all observable movement. Eventually, his "Labanotation"

was used extensively for dance and choreography (1).

"Flow" was one of Laban's elements of analysis.

It is defined as motion produced by a single effort,

or impulse to move, but which can be variously bound,

or controlled, depending on its function. Laban felt

that more tightly bound flow is more task-oriented

and is associated with labor. Less "bound,"

or freer flowing movement is associated with emotional

expression, that is, with more creative impulses.

At its most "bound," there is no visible

movement at all.

"Bound flow" refers to movement which

is held in check by certain parameters, for example

ballet or other highly codified choreography. Since

I study both martial arts and Japanese classical dance,

"bound flow" has a great deal of significance

for me. To the untrained eye, both iaido and Japanese

classical dance forms look much more "bound,"

than "flowing," or you might say, more like

work than self-expression.

To be able to discuss creativity and how it relates

to expression of both martial arts and other Japanese

arts, it is useful to examine research in this subject.

The "ura" (or hidden) meaning of my using

"bound flow" in the title of this paper

has to do with the works of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi,

whose most recent book, "Creativity" (1996),

provides some theoretical underpinnings for discussion.

"Creativity" examines the achievements

and characteristics of highly creative people, "with

a capital C" -- those who came up with some innovative

technique or strategy that is recognized within a

particular domain of study, and is further recognized

by what the author refers to as "the field",

that is, already recognized experts in a particular

area. This new discovery or approach then changes

the domain of study from that point on. The study

was based on interviews of a spectrum of well known

scientists, business people, artists and writers,

including several Nobel Prize winners.

While there are problems applying this criteria to

indigenous Asian art forms, there are nevertheless

at least some facile similarities that can be suggested

with regard to some koryu (pre-17th century) martial

arts which still exist today.

Csikszentmihalyi

notes that "creative with a capital C" individuals

are not contained in vacuums. Without exception, all

of his interview subjects are steeped in their chosen

domain of study, and have spent many hours training

in it. The archetypal founder of a koryu is usually

depicted as a seasoned warrior who spends several

days or weeks in a Shinto shrine or other sacred place,

without food or water, deep in meditation. At the

end of his ordeal, he emerges in possession of a divine

vision of what the new art form should be. He thereafter

spends years refining and perfecting his system. Only

after this period of development is it passed on to

a small group of disciples. These subsequent teachers

add their own insights, some occasionally developing

new styles altogether, others evolving and preserving

the founder's art form through successive generations. Csikszentmihalyi

notes that "creative with a capital C" individuals

are not contained in vacuums. Without exception, all

of his interview subjects are steeped in their chosen

domain of study, and have spent many hours training

in it. The archetypal founder of a koryu is usually

depicted as a seasoned warrior who spends several

days or weeks in a Shinto shrine or other sacred place,

without food or water, deep in meditation. At the

end of his ordeal, he emerges in possession of a divine

vision of what the new art form should be. He thereafter

spends years refining and perfecting his system. Only

after this period of development is it passed on to

a small group of disciples. These subsequent teachers

add their own insights, some occasionally developing

new styles altogether, others evolving and preserving

the founder's art form through successive generations.

In spite of obvious cultural differences, this archetypal

story of a ryuha founder actually fits into Csikszentmihalyi's

definition of domain-changing creative individuals,

and furnishes a basis for considering martial arts

as the product of creativity with a capital C. So

important is the story of the divinely-inspired founder,

many more modern martial art forms have also adapted

this story. In modern media involving popular interpretations

of martial arts, the "inspired founder"

is reincarnated as an inspiring teacher, for example,

Pat Morita's character in the Karate Kid movies, or

even Splinter, the rat-teacher of the Teenage Mutant

Ninja Turtles.

However, this still brings me back to my original

question: how does one determine the way in which

creativity fits in with the performance of martial

arts kata? What does that performance have to do with

flow, bound or otherwise?

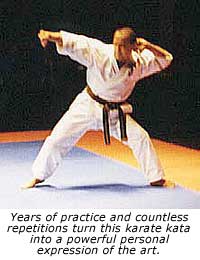

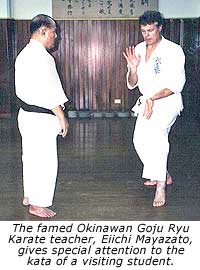

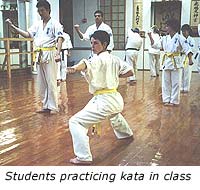

First,

we should look at kata as the building block of training.

While the origins of kata are unknown, its method

of training involves meticulously following a teacher

in the exact movements that make up the kata. Generally

speaking, martial arts kata involve scenaria of attack

and defense, though they are often expanded by arrangement

into longer sequences of attacks and defenses from

the front, back, and both sides. Students endlessly

repeat the movements, over and over, subject to correction

by the teacher and senior students. There is nothing

magical about the endless repetition of kata practice

- it really IS endless repetition. Many more traditional

teachers rarely, if ever, offer explanation for what's

being done, and are unlikely to let a student progress

until certain kata are memorized to their satisfaction,

a process that can take years. First,

we should look at kata as the building block of training.

While the origins of kata are unknown, its method

of training involves meticulously following a teacher

in the exact movements that make up the kata. Generally

speaking, martial arts kata involve scenaria of attack

and defense, though they are often expanded by arrangement

into longer sequences of attacks and defenses from

the front, back, and both sides. Students endlessly

repeat the movements, over and over, subject to correction

by the teacher and senior students. There is nothing

magical about the endless repetition of kata practice

- it really IS endless repetition. Many more traditional

teachers rarely, if ever, offer explanation for what's

being done, and are unlikely to let a student progress

until certain kata are memorized to their satisfaction,

a process that can take years.

From

the point view of someone not involved in a kata-oriented

tradition, this method of learning seems highly formalized,

codified, rigid, and dull. Many Western scholars writing

about Japanese art forms have expressed their admiration

for the fact that such highly formalized art forms

like kabuki can still be entertaining (though some

writers actually find kabuki performance just as rigid

and non-creative as the training). Personally, however,

I find many traditional Japanese art forms compelling,

theatrical, and very powerful. Given the formal rigidity

of kata, how can this be? From

the point view of someone not involved in a kata-oriented

tradition, this method of learning seems highly formalized,

codified, rigid, and dull. Many Western scholars writing

about Japanese art forms have expressed their admiration

for the fact that such highly formalized art forms

like kabuki can still be entertaining (though some

writers actually find kabuki performance just as rigid

and non-creative as the training). Personally, however,

I find many traditional Japanese art forms compelling,

theatrical, and very powerful. Given the formal rigidity

of kata, how can this be?

To consider some of the deeper functions and meanings

of kata, I would like to rely on my experience in

iaido, the art of drawing the sword. As in kabuki

and Japanese classical dance, training for this particular

martial art is primarily through kata, since it is

difficult to spar with a sword. The high level of

respect accorded to swords in Japan as well as the

extremely dangerous nature of the weapon and techniques

being learned make the formality of kata for iaido

a compelling necessity. Iaido kata make up not only

the learning process of the art form but the content

of it as well.

In this case kata practice teaches technique, strategy,

and perhaps, after many years of practice, the underlying

principles of iaido. By "underlying principles,"

I mean the logic of the movement - why the hardworking

and divinely inspired developers of the ryuha (school

or tradition of teaching) decided to do it THIS way

and not THAT way.

On

the face of it, one might assume that the study of

iaido would contribute hugely to an argument for rigidity

and lack of creativity. Fuel for this argument can

be readily obtained in the way many people, both in

Japan and the US, currently practice the art form.

Emphasis is relentlessly placed on correcting the

smallest details of kata, and larger principles seem

to be devalued. However, this is not really the case.

After many years of imitating teachers and senior

students, practitioners are eventually able to move

beyond, or through, technique. All the technical aspects

of the kata are still intact and can be seen by observers,

but the way in which the kata is performed becomes

highly individualized. In our Dojo, we refer to this

as "owning the kata." Iaido then goes from

being "about as much fun as watching paint dry,"

as one observer of junior students put it, to an art

form that is both beautiful and somewhat daring in

its execution (Prough 1996). On

the face of it, one might assume that the study of

iaido would contribute hugely to an argument for rigidity

and lack of creativity. Fuel for this argument can

be readily obtained in the way many people, both in

Japan and the US, currently practice the art form.

Emphasis is relentlessly placed on correcting the

smallest details of kata, and larger principles seem

to be devalued. However, this is not really the case.

After many years of imitating teachers and senior

students, practitioners are eventually able to move

beyond, or through, technique. All the technical aspects

of the kata are still intact and can be seen by observers,

but the way in which the kata is performed becomes

highly individualized. In our Dojo, we refer to this

as "owning the kata." Iaido then goes from

being "about as much fun as watching paint dry,"

as one observer of junior students put it, to an art

form that is both beautiful and somewhat daring in

its execution (Prough 1996).

The Japanese explanation for this progression is

"shu-ha-ri." "Shu" means conservative,

sometimes interpreted as "tradition" --

the period in which one learns all the kata pertaining

to the style by heart. "Ha" means "break,"

and is often referred to as "breaking with tradition,"

but I think this is incorrect. Instead, I think "ha"

means "breaking through the technique" by

actually evolving through it rather than discarding

it. "Ri" means "freedom": a state

in which the techniques become so embedded in the

practitioner that they can be expressed in free-flowing

movement. In other words, the beginner is totally

immersed in Laban's workman-like bound flow process

of learning kata, and eventually moves beyond it to

the much less bound flow process of the expert practitioner,

ever closer to the creative flow experience.

Shu-ha-ri takes a lifetime. My teacher, Yoshiteru

Otani (1998), says each phase takes 10 to 15 years

to complete. So, with diligent practice, it takes

20 to 30 years to reach Ri, and then, only with some

luck. Many practitioners give up out of boredom or

frustration before reaching this state, and some,

though they practice and practice, never achieve it.

On the other hand, technique learned through kata

moving through the process of shu-ha-ri can potentially

become a springboard for creativity.

In this way, iaido training is similar to both Japanese

classical dance and kabuki. One dancer with whom I

recently spoke suggested that kata is like the Tardis,

the phone booth/time travel machine of Dr. Who (I

would have suggested Valantino's tent in Son of the

Sheik) - it looks small and confined on the outside,

but it's endlessly large on the inside (Moss 1998

n.p.).

Therefore, when someone tells me that he was bored

at a traditional (that is, a non-sport) martial art

demonstration, I tell them with some confidence "what

you saw was probably not very good," or, else

"They were probably beginners;" that is,

the practitioners were stuck in shu, a state that

has interest for them, but for no one else. In the

hands of a master, for example Shibata Kanjuro in

kyudo, Nakayama Hakudo in iaido, or even my own teacher,

Otani Yoshiteru, these very formalized art forms take

on life and expressiveness.

Why is kata uniquely suited to these art forms? Why

don't people learn as well from technique drills,

or from videotape? An argument can be made that kata

practice as a teaching method became popular because

it acted as a physical encyclopedia, preserving the

form from the teachers' to the students' bodies over

generations. With the advent of videotape and CD-ROM

disks, its use seems less important now that these

forms of recording or reproducing movement are available.

But this is not the case. In fact, an experienced

practitioner can easily pick out the student who has

studied from videotape without benefit of a master

teacher (2). In contrast, kata practice, with a live

teacher, provides a progressive form of "deep

learning" which does not seem to be attainable

in any other way. Endless repetition in striving to

replicate exactly what the teacher is doing, in all

its variations, deeply imbeds not only that technique

of the art form being learned, but also builds the

meaning of the movement being done.

The martial arts student is learning not just the

content of the curriculum of the style but also the

tactics, techniques, and hopefully the underlying

principles that make up the particular style of martial

art form he or she is studying. Shu-ha-ri is often

described as circular, but I think "spiral"

might be more accurate: in the beginning, the student's

movements are awkward and express nothing so much

as his physical self with what he has initially brought

in terms of experience to the dojo, to the stage where

he becomes expert at imitating his teachers and seniors,

to the point where he can once again express himself

through this new, codified movement. In terms of the

spiral, the student is crossing that point where she

began, but unlike the circle, she crosses it at a

higher level. (3) In the Laban sense, though still

bound, the flow of movement becomes freer and more

expressive, approaching the Csikszentmihalyi definition

of creative flow.

There is simply no way drilling in abstract techniques

and sparring for martial arts to create a similar

result, though this type of training is considered

"more efficient." We are already seeing

this in highly sportified forms, where tournament

results take precedence over any form of deep learning.

The result is legions of students, which is to say

quantity, who really have no idea what they're actually

doing. This may mean income for the teacher for the

present, and the loss of the art form further down

the road, as people trained in this method lack the

depth imparted by kata training and become bored as

a result.

For us mere mortals, Csikszentmihalyi concludes "Creativity,"

by suggesting ways for us to become more creative

in our daily lives. He notes that individuals who

make time for creative activity, learn to focus, strive

to stay disciplined and find a direction to channel

focused energy can enrich themselves by being more

creative. Dedicated martial artists (or artists of

any kind) fit this definition very well.

A few extraordinary and innovative martial artists

have founded or modernized their arts -- Kano Jigoro

(judo), Ueshiba Morihei (aikido), Nakayama Hakudo

(iaido) and Funakoshi Gichin (karate-do). Each could

be said to have changed his area of study for posterity,

and impressed the field, that is, leading teachers,

if not in their lifetimes, then certainly afterward.

Each was first "deeply steeped in their discipline(s)"

of study before they took a unique approach to a situation:

how to preserve and perpetuate martial arts in a rapidly

modernizing and increasingly forgetful world.

Notes

1- Laban divided movement into four elements: weight,

space, time and flow, through which he felt virtually

every movement could be recorded on paper. Flow, it

should be noted, is affiliated with, but separate

from, rhythm (beats distinguished by an interval of

rest). Pioneering anthropologist Franz Boaz employed

a ballerina trained in the method to record movements

of work and play of Native American tribes of the

Pacific Northwest, though one of the problems with

the method is interpretive; i.e. different cultures

don't necessarily assign the same values to the elements

Laban uses for analysis. Labanotation was also expanded

to recording everyday movement and folk dances of

peoples around the world. Laban's system of notation

was (and still is) used mostly to record dance and

choreography.

2- Video tape learning is problematic at best. For

one thing, the practitioners are seen in miniature

and subtleties of movement cannot be recorded by the

speed of the camera. The student who uses tape is

also often at a loss when the practitioner turns away

from the camera if other angles are not seen. Another

problem is the tape is exactly the same, and any depth

the living practitioner may have is flattened out.

Movements and their origin are easily misinterpreted

or missed altogether. Perhaps most importantly, the

life span of videos or even CD-ROM are limited; videos

by the instability of the recording medium itself,

and CD's by the constantly changing technology which

makes accessibility a problem after a short span of

time. Therefore, individuals who feel they are able

to master a set of movements in part because they

"have it on tap" are making a mistake on

a number of levels.

3-I am indebted to Margaret Thompson Drewal (1992)

for the concept of the spiral, rather than a circle,

in describing repetition of actions over time.

Bibliography

Csikszentmiahlyi, Mihaly1996: Creativity: Flow and

the psychology of discovery and invention (New York:

Harper Perennial).

Drewal, Margaret Thompson1992: Yoruba Ritual: Performers,

Play, Agency (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana

University Press).

Friday, Karl1998: Personal communication

Laban, Rudolf1988: The Mastery of Movement (Plymouth,

UK: Northcote House).

Moss, Helen E.1998: Personal communication

Otani Yoshiteru1998: Interview with the author.

Prough, John1996: The Iaido Newsletter (Toronto:

Sei do kai Pub.).

Let

Us Know Your Comments & Opinions On This Article

About The Author:

Deborah Klens-Bigman is Manager and Associate Instructor

of iaido at New York Budokai in New York City. She

has also studied, to varying extents, kendo, jodo

(short staff), kyudo (archery) and naginata (halberd).

She received her Ph.D in 1995 from New York University's

Department of Performance Studies where she wrote

her dissertation on Japanese classical dance (Nihon

Buyo). and she continues to study Nihon Buyo with

Fujima Nishiki at the Ichifuji-kai Dance Association.

Her article on the application of performance theory

to Japanese martial arts appeared in the Journal of

Asian Martial Arts in the summer of 1999. She is married

to artist Vernon Bigman.

back

to top

home

| about

us | magazine

| learning

| connections

| estore

|