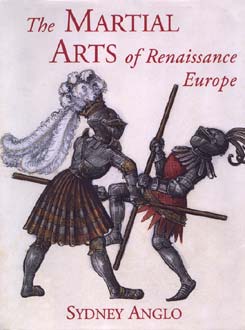

The Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe

by Sydney Anglo

Yale University Press, $45

ISBN: 0-300-08352-1

Review by Ken Mondschein, FightingArts.com Staff

Miyamato Musashi is well known amongst martial artists

as a great swordsman of sixteenth- and seventeenth-

century Japan, but how many have ever heard of his

Italian contemporary, Ridolfo Capo Ferro? For those

with an interest in the European counterparts to kenjutsu,

jujutsu, and the other warrior arts of Japan, "The

Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe" by Sydney

Anglo is well worth picking up. Though suffering somewhat

from a lack of perspective, the book still provides

a good overview of European fighting systems as they

existed from the late Middle Ages to early modern

times, and as their teaching and practice related

to society at large. Accordingly, while some of those

who have spent years and decades studying fencing

and other Western fighting arts may disagree with

some of Dr. Anglo's conclusions, his book still provides

the general reader with a decent introduction to the

arts of war and self-defense as they existed in early

modern Europe and one view of conclusions to be drawn

from them.

Miyamato Musashi is well known amongst martial artists

as a great swordsman of sixteenth- and seventeenth-

century Japan, but how many have ever heard of his

Italian contemporary, Ridolfo Capo Ferro? For those

with an interest in the European counterparts to kenjutsu,

jujutsu, and the other warrior arts of Japan, "The

Martial Arts of Renaissance Europe" by Sydney

Anglo is well worth picking up. Though suffering somewhat

from a lack of perspective, the book still provides

a good overview of European fighting systems as they

existed from the late Middle Ages to early modern

times, and as their teaching and practice related

to society at large. Accordingly, while some of those

who have spent years and decades studying fencing

and other Western fighting arts may disagree with

some of Dr. Anglo's conclusions, his book still provides

the general reader with a decent introduction to the

arts of war and self-defense as they existed in early

modern Europe and one view of conclusions to be drawn

from them.

Dr. Anglo introduces us to such people as Pietro

Monte, acquaintance of Leonardo da Vinci and trainer

of the best warriors of Renaissance Italy; Hans Talhoffer,

master of a fifteenth-century system of German swordsmanship

that has been compared in complexity and depth with

Japan's most famous schools of swordsmanship; and

Jeronimo de Carranza, a sixteenth-century Spanish

nobleman whose geometrical conceptions of swordsmanship

have passed into legend as the "mysterious circle."

This is fascinating reading for those previously unaware

of the variety and history of European arts.

Anglo addresses various subjects, such as the place

of the fencing master, the teaching of martial arts

in society (a subject perhaps better treated by Arthur

Wise's "Art and History of Personal Combat")

and the pedagogical problems related to the notation

and illustration of movement in combat manuals. His

answers to the latter question are interesting, and

certainly of interest to those who practice and teach

Asian martial arts. He also deals with the use and

practice of such weapons as swords, staff weapons,

knives, bare hands, and mounted combat with swords

and lances.

However, in today's society, the term "martial

arts" unfortunately all too often means simply

"that which enables one to dispatch any opponent

quickly and efficiently." Whereas there is a

growing awareness that there is much greater depth

and beauty to the martial arts than mere kicking,

punching, and bone-breaking, some of Dr. Anglo's conclusions

seem to have been fueled by this popular modern misconception,

without specific reference to the norms of Renaissance

Europe. For instance, in his final chapter on "duels,

brawls, and battles," Dr. Anglo seems to say

that there is indeed little difference between the

three scenarios, and compares the civilian martial

art of rapier fencing to commando-style "all-in

fighting." Regardless of the fact that the true

intention of the skillful use of the rapier is to

keep the adversary at distance and kill him there,

this attitude is contrary to some of the best thinking

on the subject. J. Christoph Amberger has pointed

out in his "Secret History of the Sword"

that there is a definite difference between combat

in war and personal combat fought under a set of rules,

and between mass combat and the predatory, cold-blooded

dispatching of an adversary. Perhaps a study of hopology,

or a perusal of Donn Draeger's works, would have stood

Dr. Anglo in good stead.

Still, read with an open mind, "The Martial

Arts of Renaissance Europe" is a good read, and

a useful introduction to the subject.

return

to reviews

back

to top

home

| about

us | magazine

| learning

| connections

| estore

|